Carbon dioxide removal is needed alongside emissions reductions to achieve Australia’s net zero goals, a new report has found.

Led by the University of Oxford, the report released today is a global stocktake of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) — where it’s at, what it entails, and where to go from here. It delves into technology tried, tested, and still up in the air, making clear that although CDR is “not a silver bullet”, it needs to be aggressively scaled up.

“CDR is about where renewables were 25 years ago,” University of Wisconsin-Madison lead author Gregory Nemet said in a briefing to journalists on Wednesday.

CDR pulls two gigatonnes of carbon dioxide annually from the air. In line with countries’ commitments, that figure is set to rise to 2.6 gigatonnes by 2030 and 2.9 gigatonnes by 2050. And yet the report finds these numbers utterly out of step with what’s needed to meet Paris Agreement targets. It’s been coined the “CDR gap”.

In Australia, the public conversation and policy settings are not where they need to be to implement CDR fast and at scale, said Australian National University PhD scholar and lecturer in climate policy Aaron Tang.

Although the removal is built into Australia’s climate change bill and its use implied, Tang said there was “nothing yet, which explicitly says: ‘Alright, we’re doing CDR this much within this timeframe’.”

Under the Morrison government, CDR was folded into any and all emissions reductions rhetoric and rollout, with 15% of Australia’s 2050 abatement allocated to yet-to-be-revealed CDR technology. The removal was framed as a complete substitute rather than a necessary supplement to emissions reductions and conflated with processes like carbon capture and storage (CCS), which the report makes clear does not count as CDR.

CCS relates to CO2 that comes “directly from fossil fuels or minerals” and therefore comes under emissions reductions. Same game for carbon capture and utilisation (CCU). This is an industrial process for “chemical capture” of CO2.

So what exactly is CDR?

In short, it’s the process of taking carbon dioxide from the air and storing it for “decades or millennia” (the latter is preferred) in land, geological formations, oceans, or in products. CO2 must be atmospherically derived and be willing to do time to qualify for CDR.

CDR has two hats: conventional (on land) and novel (everything else). The former is effectively tree planting and accounts for 99.9% of all CDR. The remaining 0.1% comes from novel methods, many of which have not fully passed the pub test and include question marks over potential adverse environmental impacts.

But the report prioritises investment in research, development, implementation, and monitoring of these novel methods, declaring it needs to be scaled up by a factor of 30 by 2030 and 1300 by 2050.

“The amount of CDR deployment required in the second half of the century will only be feasible if we see substantial new deployment in the next 10 years,” the report concluded.

Let’s take a look at the technology we have to play with.

Conventional CDR

This is as simple as planting trees to shore up forests, reinvigorating damaged patches of bushland, peatland or wetland, establishing something new, or applying the same principles to agricultural contexts (formally called “agroforestry”). Wood is a good reserve for carbon even once cut down, so wood products are included in the conventional game.

The downside? CDR rates in forestry are not constant, susceptible to growth and weather.

“As forests reach maturity, the rate of growth slows right down so if you want to keep CDR on land through reforestation, you’re going you have to plant up new areas,” report author and senior principal research scientist from the NSW Department of Primary Industries Dr Annette Cowie said.

Soil carbon sequestration is another flagship method in the conventional camp. The healthier the soil, the more carbon rich it becomes so CDR is about building organic matter to improve carbon retention rates (and boost agricultural productivity). But like forestry, anything siloed in soil is vulnerable to loss if the plant matter feeding it falls flat.

Enter Biochar. The biomass derivative — effectively charcoal — is added to soil to stimulate its nutrient and water-holding capacity. It’s made in a low-oxygen environment and simultaneously produces bioenergy (therefore a good substitute for fossil fuels).

Novel CDR

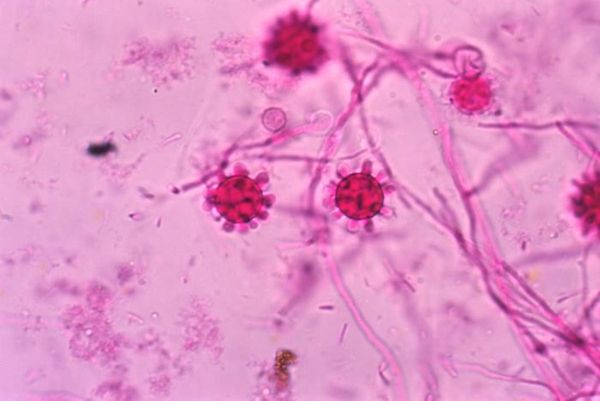

Anything not stored in the land comes under “novel” CDR. In the ocean, there is pioneering technology to alter alkalinity and fertilise marine areas. But these methods come with warnings on ecosystem productivity and marine health, including unwanted algae blooms. It’s also unclear just how much carbon these methods would effectively store.

Then there’s bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), which is the burning of plant material for energy. It’s a viable option to displace fossil fuels, but questions remain over reliability of resources, how it might intervene with land preservation practices, and its impact on air quality.

Compare this to direct air carbon capture and storage (DACCS), which uses a fan system and solvents to extract CO2 that’s then condensed and stored geologically or used in building materials. Alternatively you can increase the capacity for rocks to absorb and store carbon via a process called enhanced weather of rocks, which basically crushes it up and redistributes it on land.

With many unknowns and variables, Nemet said it was critical to pursue a “portfolio of solutions”.