It was weeks before Christmas in 2021 and bitterly cold when Kathleen Campbell opened a package from an unknown company.

“The company was called Navigator, who said they were building a pipeline, and they were asking us for an easement, but that, if we refused, they would condemn our property and ask for eminent domain,” says Campbell, 71, a central Illinois resident who lives in Glenarm. “I suddenly felt sick to my stomach and started panicking. I didn’t even know they could do that.”

Campbell and her husband Craig Campbell bought the home in the 1980s. They planned to spend their retirement enjoying their one-acre lot, with its seven gardens, organic vegetation and fountain.

Suddenly, those plans were at risk.

Navigator CO2 Heartland Greenway was embarking on a project to build more than 1,000 miles of pipeline through five states, ending in central Illinois. That pipeline would transport highly pressurized liquid carbon dioxide.

“After I got over my panic, I started reading about the project and other projects like this,” says Campbell, who’s now part of a coalition working to stop the pipeline. “I am not an activist by nature. But I became an accidental activist, and we are working to be protected from this kind of project.”

According to environmental groups, Illinois is at the precipice of a rush of corporations coming in to the state to lay thousands of miles of pipelines without the proper protections in place for neighboring residents.

The goal of the pipeline is to capture carbon dioxide in a liquified state from factories or power plants before it can be released into the atmosphere, then transport it in the pressurized pipeline and store it deep underground — a process billed as a way to clean up dirty industries and reduce carbon emissions.

Carbon capture and storage has been around since the 1920s, though it didn’t become commercialized until the 1970s. And it hasn’t been until the past two decades that it began being seen as a way to address the climate crisis.

But environmental groups including the Sierra Club Illinois are skeptical it can deliver on its promises.

“We are poised to be a ground-zero state for this carbon capture, utilization and storage industrial process, and we don’t have the adequate protections in place,” says Christine Nannicelli, Sierra Club Illinois’ Beyond Coal campaign representative. “There are a lot of question marks, and we have an enormous amount of skepticism about how effective it will be for a climate solution.”

A flood of federal dollars has triggered a gold rush for companies across the country to embrace carbon capture and storage pipelines nationwide.

And the geological makeup of Illinois has made it a prime location to not only transport carbon dioxide but also store it. The state’s underlying Mount Simon sandstone, deep underground — it can exceed 3,200 feet thick — is described as able to hold the carbon dioxide in a liquid state. A layer of impermeable rock lies above the formation, which can keep the carbon dioxide from rising to the surface.

Andy Bates, a Navigator spokesman, says central Illinois is ideal because of these properties and would “allow for safe, permanent storage of” carbon dioxide.

“There’s extensive work that has been completed by the U.S. Department of Energy and the Illinois Geologic Survey teams that lead to this area being one of the most researched and now well-understood geologic formations in the country,” Bates says.

Navigator filed for a permit in February to build and operate a pipeline that would transport captured carbon dioxide emitted by facilities in Illinois, South Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska. The carbon dioxide would then be injected into permanent underground storage.

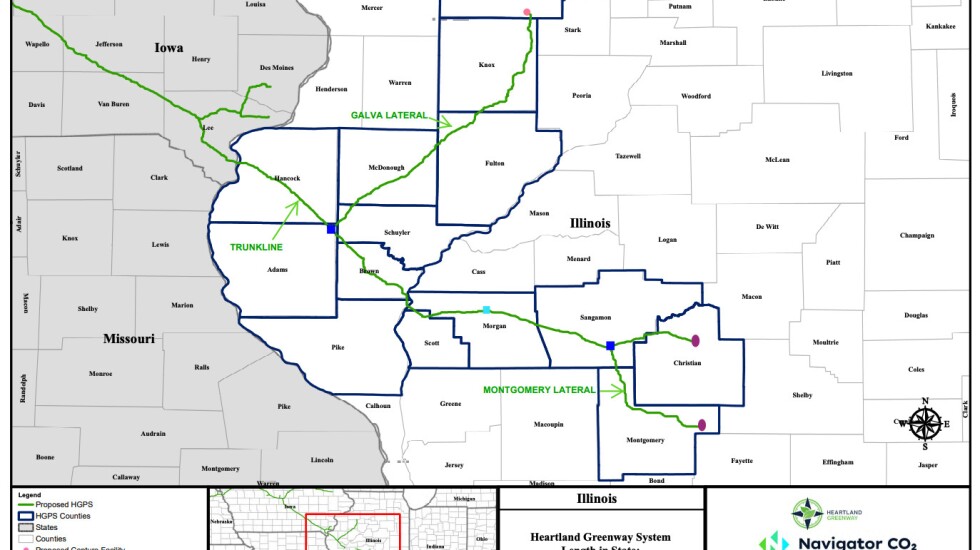

The 1,350-mile pipeline would travel through the five states, with 21 collection sites. The Illinois portion would have about 292 miles of pipeline in 13 counties, starting in Hancock County to the west and splitting north to Henry County and southeast to Montgomery County.

If approved, work could begin as early as the second quarter of 2024.

Navigator isn’t the only pipeline project planned in Illinois. Wolf Carbon Solutions is trying to develop a 280-mile carbon dioxide pipeline beginning in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and ending in Decatur.

The Biden administration has ramped up funding to build a carbon dioxide removal industry. In February, it announced plans to provide $2.5 billion to accelerate carbon capture, transport and storage systems.

And the federal Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 significantly increases the tax credits for these projects, going from $50 per metric ton for carbon dioxide storage to $85.

The Navigator project is expected to capture, transport and store up to 10 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually — possibly getting $850 million a year in tax credits.

“Given how lucrative these new subsidies are at the federal level, the industry is looking for a blank check to run wild in different parts of the country, and Illinois is looking like a good spot for them,” Nannicelli says.

‘Land can be cannibalized’

For Campbell, a key concern is the threat of corporations coming in and seizing part of her property through eminent domain — a process used to take over private land for public use.

“I find it terrifying that anyone can come and just take part of your property,” she says. “Like what kind of property rights do we have here? This can leave a lot of people in trouble.”

Navigator’s permit application requested this power, saying it needed the ability “to take and acquire easements and interest in private property” through eminent domain if a landowner refuses to negotiate while also saying it’s committed to negotiating in good faith with property owners.

“We take this process very seriously and understand its significance to our agricultural industry and affected landowners,” Bates says.

Nannicelli says there are no protections for Illinois property owners from corporations in such situations and that farmers who need their land for survival are most at risk.

“Companies like Navigator are essentially saying they have rights to these families’ land, and these families are feeling legally threatened that their land can be cannibalized,” Nannicelli says. “It’s a land grab … And, from our perspective, this is technology and a process that serves corporate interest far more than the public.”

Ariel Hampton, legal and governmental affairs manager for the Illinois Environmental Council, says this practice can allow companies to bully property owners into agreeing to their terms.

“It is super-important for folks to feel comfortable and safe in their homes and not feel that some entity can come in and take what doesn’t belong to them,” Hampton says. “We don’t want folks dealing with the burden of a private company coming in and disrupting their lives while that company makes a ton of money off federal incentives.”

Environmental advocacy groups including the Illinois Environmental Council and Sierra Club Illinois want legislators to pass a law allowing for tougher regulations on companies building pipelines and to prevent those companies from using eminent domain authority.

“The bill, HB 3119, would also make owners and operators actually liable over the pipeline and prevent that liability being transferred to the state and taxpayers after a company is done with the injection and meets a few requirements,” Hampton says. “We need the operators to do the monitoring and the post-injection care and report out rather than it becoming the state’s liability and therefore the taxpayer’s liability.”

Safety’s another concern, Campbell says.

“I come from a plumber’s household, and I know pipes rupture all the time,” Campbell says. “We know what happened in Satartia already.”

That’s Satartia, Miss., where, a pipeline carrying carbon dioxide ruptured in 2020, gushing a dense, powdery white cloud that sank into the ground and was “cold enough to make steel so brittle it can be smashed with a sledgehammer,” according to a Huffpost investigation.

Nearly 50 people were hospitalized, and about 300 people evacuated the area.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, a federal agency responsible for pipeline oversight, found that it needed to strengthen its safety oversight of carbon dioxide pipelines following its investigation into the disaster.

“I think that everything is a risk-benefit analysis, and these projects’ risks far exceed the benefit,” Campbell says. “There is no doubt we have a climate problem, absolutely. But this pipeline is too dangerous. Solar and wind projects are so much safer. Why aren’t we investing all that money into that?”