In an exclusive extract from Angela Walker's book, Ideals Are Like Stars: The Dame Yvette Williams' Story, it's a year out from the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, and Williams reveals her innovative and demanding training regime, including flying off the St Clair sand dunes.

Before she went to sleep on Thursday, 19 July 1951, Yvette sat up in bed with her diary balanced on her lap. As usual, it had been a full and productive day. Between arriving home from work and leaving for her two-hour winter training session, Yvette had finished the jersey and hat she was knitting for her father, and had written a couple of letters. Now, about to record the events of the day, she noticed the date, and picked up her blue pen. ‘One year today is the opening of the Olympic Games in Helsinki,’ she wrote. ‘So I just wonder if I’ll be there. Either that or doing housework I suppose.’

She wasn’t the only one wondering whether she would be selected for the New Zealand Olympic team, with candidates for the 1952 Games being considered in the sports news. There was also the question of how the team would travel to Finland, The Evening Star making the case that the next New Zealand Olympic team should be the first to have the benefit of air travel. Recognising what an expensive proposition this would be, the newspaper proposed the creation of sports stamps carrying a surcharge. Examples from other countries that had financed their Olympic teams this way were given, along with a potential design for the stamps featuring Yvette throwing the javelin. In the days that followed, letters to the editor were published, largely in support of the idea.

The Bellwoods’ opinion on Yvette’s preparation was sought, their wide European experience and first-hand knowledge of the Helsinki environment and track conditions acknowledged. ‘Every effort is being made to see that Miss Williams will leave New Zealand fully prepared physically and mentally to do justice to the important role she seems certain to be asked to fill,’ one article declared. ‘If a decision is made to fly the New Zealand team about three weeks before the games, so as to allow two weeks for the final sharpening up, no serious difficulties are contemplated in Miss Williams’s preparatory schedule.’

A series of editorials and articles called into question the rigorous standards employed by the Olympic selectors, after a member of the Olympic Committee was quoted saying, ‘Only New Zealand’s best athletes and, even then, only those with a winning chance would be sent to the Helsinki Olympics’; adding, there was no need to raise money by issuing stamps, with so few New Zealand competitors likely to be selected. Another article responded with the claim the Olympic body had a ‘cold water’ policy and shouldn’t be throwing a ‘wet blanket on amateur sport’, adding: ‘Why not then send as large a team as possible to Helsinki and thus reap the benefit at the British Empire Games in Vancouver.’ The debate raged on. There did, however, seem to be a consensus on one thing: Yvette Williams was, as one headline shouted, a ‘sure thing for the Olympics’.

But nothing was certain as far as Yvette was concerned. She had seen how few New Zealand athletes had been selected for the 1948 Olympic team, with only three for track and field events, and all male. Only seven women had ever previously been selected for New Zealand Olympic teams: five swimmers — Violet Walrond, Gwitha Shand, Ena Stockley, Kathleen Miller and Ngaire Lane; and two athletes — Norma Wilson and Thelma Kench. Yvette cut out every newspaper article that appeared about the upcoming Olympics, looking for clues as to her fate, despite a selector telling her that they wouldn’t be making the selection criteria public.

Mrs Bellwood’s year-long convalescence in hospital continued, but it no longer prevented her from contributing to Yvette’s athletics schedule. From her hospital bed, she wrote out Yvette’s training programmes complete with miniature illustrations depicting how to perform each exercise. Yvette visited her regularly to collect her latest programme. She would often find Mrs Bellwood doing embroidery or crosswords to pass the time. On one visit, Mrs Bellwood came up with the idea of engaging a professional photographer to capture Yvette’s training schedule in a series of images. Yvette spent the ensuing weeks having photo-shoots with well-known local photographer Mr Edward Arthur Phillips.

The first one took place on the coldest Monday evening of the year.

On Sunday, the weather was vastly improved. By the time Yvette met Mr Bellwood at the beach at 10am, the early morning frost had thawed and the skies were clear. The beach was Yvette’s favourite place to train. She never minded having to get out of bed for Sunday beach workouts, even though she was usually sleep-deprived after a Saturday night out.

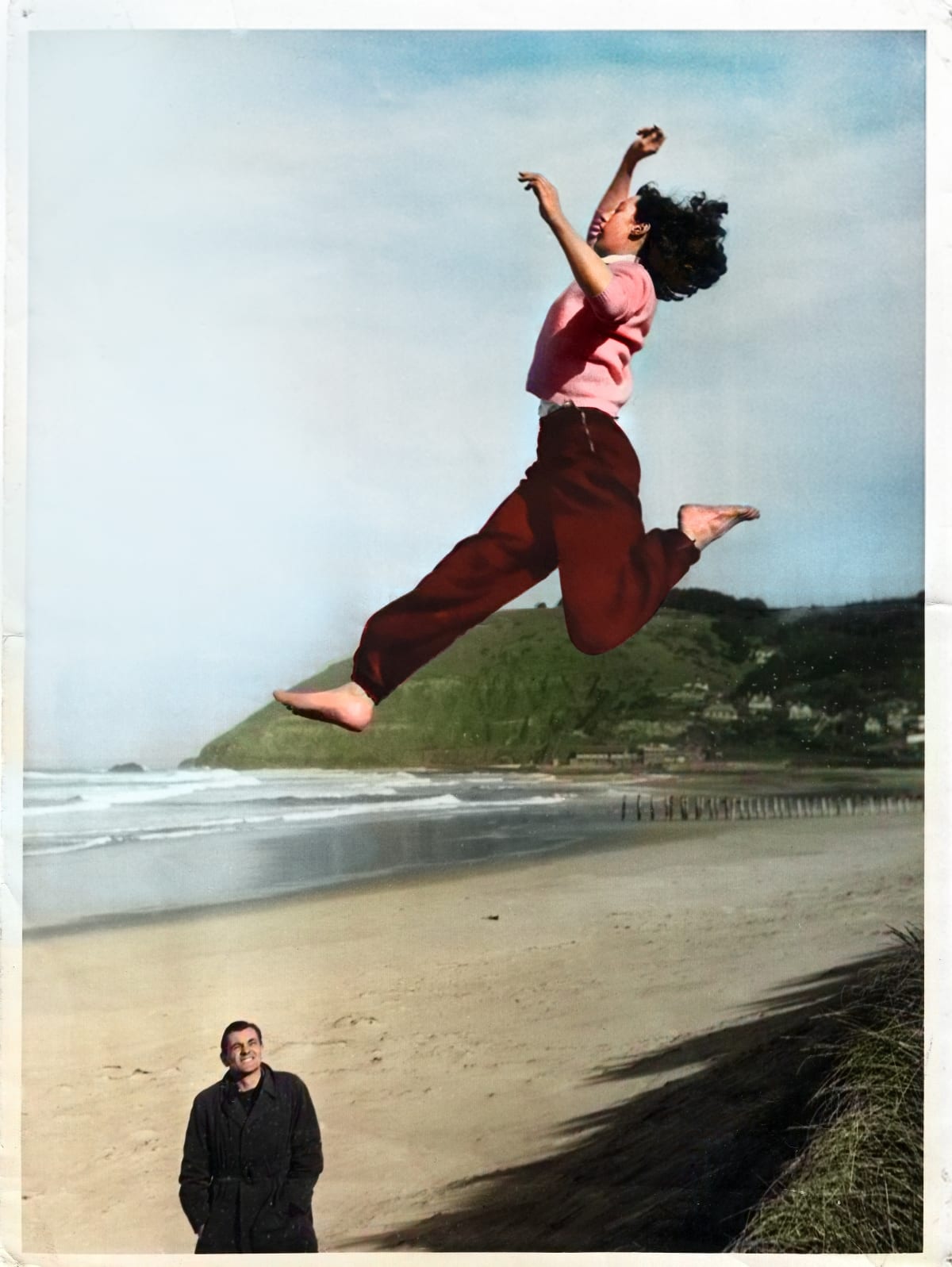

Mr Phillips arrived armed with his camera and tripod. He explained that he wanted to photograph her leaping off the sand hills, showcasing her signature hitch-kick. Mr Bellwood, wrapped in a long woollen coat with his hands in his pockets, stood at the bottom of the dune, while Yvette, in training pants and a short-sleeved top, waited high above for the photographer’s signal. He pointed his lens in the direction of the St Clair headland and nodded at Yvette. She sprinted towards the tide, leaping up and off the top of the dune. Click. Mr Phillips captured her perfectly, at the zenith of her jump, right leg stretched forward, left leg tucked in behind, arms gracefully swung overhead, Mr Bellwood far below casting an appraising eye, all framed by the long stretch of sandy beach. Here was Yvette mid-flight, the unbridled joy of the great outdoors, a young woman full of courage and ambition envisioning what the future might hold. Mr Phillips had taken an iconic photograph to treasure.

The following evening he arrived at Yvette’s home to photograph more of her training regime. He began with some shots of her throwing the discus into her training net in the backyard. Her father had recently constructed a throwing circle complete with a net and trough to catch the discus. Since the javelin event had begun to hurt her back and niggle her elbow, Yvette was now focusing more on discus. She proceeded to do Mrs Bellwood’s list of exercises. Mr Phillips captured her lying on her back performing leg-raises with a medicine ball locked between her ankles. Once she had completed the set, Mr Phillips wanted to know what she typically did after training.

Winnie popped her head into the room. ‘She’s always sewing.’

Yvette agreed to sit hunched over her sewing machine, hair tucked behind her ears. She masterfully guided the lemon seersucker frock she was making under the needle. Click.

More photos were taken at the winter training school later that week: Yvette performing trunk swings, Yvette using the hanging ropes. Mr Phillips even attended her next badminton tournament. It was the winter sport she had replaced basketball with, in order to reduce injury risk during her Olympic build-up. Mr Phillips snapped her poised to hit the shuttlecock, racket outstretched.

The collection of photos soon appeared in The New Zealand Sportsman. Its cover featured an eye-catching picture of Yvette leaping off the sand hills. ‘From Monday to Friday — A Peep at the Varied Training Schedule of Yvette Williams’ the article inside headlined. Yvette’s typical winter training schedule was itemised alongside a series of pictures: badminton on Monday, resistance training at home on Tuesday using sandbags and a medicine ball, winter training school on Wednesday and Thursday, day off on Friday, discus training in the backyard on Saturday, beach workout on Sunday. In addition, Yvette walked to and from work every day, rode her bike to training, and squeezed Mrs Bellwood’s 30-minute daily programme into her relentless schedule. The Bellwoods prescribed such variety for Yvette, the article explained, to ‘relieve monotony, sustain interest, and bring her to a pitch of physical perfection’.

In what little spare time Mr Bellwood had — in between coaching, caring for his two toddlers, and visiting his wife in hospital — he had taken to researching and writing articles for sports magazines to try to make ends meet. In the course of his research, he often came across innovative ideas and breakthroughs in sports science. One day he rang Yvette to tell her about an article in the latest English athletics magazine that extolled the virtues of rest and sleep. Ten hours per night, the article said, was recommended. Mr Bellwood told Yvette that she needed to be in bed by nine o’clock every night from now on, and asked her parents to enforce it. Inherently a night owl, Yvette was often up late. She handled lack of sleep well and thought nothing of getting less than eight hours, regularly prioritising her social life over retiring to bed early. At the expense of having fun, sleeping more was going to be tough, but she resolved to at least try.

One of the topics Mr Bellwood wrote about that year was an innovative training method he himself had developed. His idea had been born from a problem: Yvette’s jumping style had been perfected to the point where the incremental gains she had been making had now plateaued. Essentially, adapting her technique any further was fruitless. Mr Bellwood figured that further development of any consequence was only possible if she could cultivate more speed in her run-up. He knew European distance-runners sometimes trained at slightly faster speeds than they raced, rather than shuffling around at rates that bore no resemblance to the pace they were aiming for. Mr Bellwood wanted to apply the same principle to sprinting, but the question was how; a sprinter was already running flat-out. If he could somehow get Yvette practising faster sprints, he was sure her body would adapt, embedding the greater speed within her mental and physical wiring.

That is when he hit upon the idea of downhill sprints. Immediately, he replaced her usual practice sprint starts with 50-yard sprints descending a slight gradient. The grassy embankment on the northern slope of the Calé provided the ideal gradient. Mr Bellwood’s hunch proved correct: it wasn’t long before Yvette was able to sprint faster on the flat, and the distances she was jumping began to increase again. Now, in the sprint races, she sometimes even beat national champion Shirley Hardman.

Mr Bellwood had dreamed up a sprint-training loophole for Yvette to exploit. His approach wasn’t without controversy, other coaches disputing his methods, but Mr Bellwood was undeterred. The results he was achieving with Yvette spoke for themselves.

* Ideals are like Stars: The Dame Yvette Williams Story by Angela Walker, published by Bateman Books, RRP$39.99. Available in all good bookstores.

LockerRoom editor Suzanne McFadden will chat with Angela Walker about her experience writing the book at a virtual launch on Facebook on Thursday at 7.30pm.