To bolster its rapidly-growing tech sector, the Canadian government introduced the Tech Talent Strategy in June 2023 with the aim of attracting workers and entrepreneurs. As a part of this strategy, the government announced improvements to the Start-Up Visa program.

The Start-Up Visa program is designed to help foreign entrepreneurs gain permanent residence in Canada. Initially introduced as a five-year pilot project in 2013, it was created to replace the longstanding Federal Entrepreneur Program that had been in operation since the 1970s.

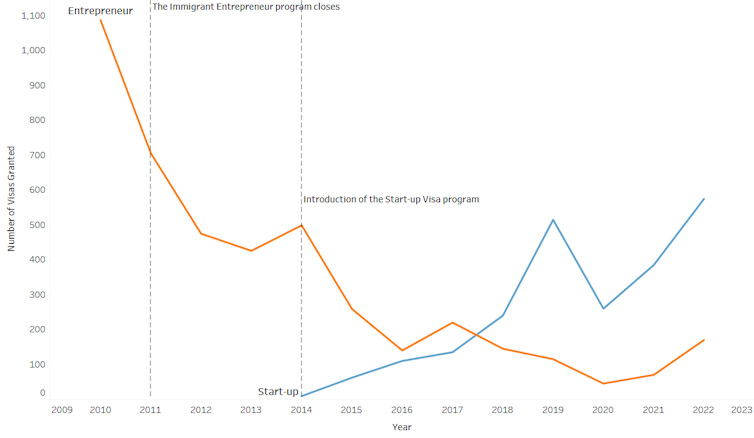

However, the Start-Up Visa program has not proven to be a suitable replacement. Although the program has grown over the years, our analysis found that it’s still only half the size the Federal Entrepreneur Program was in 2010.

The Start-Up Visa program is falling short in a number of key areas, including job creation, global trade opportunities and the long-term viability of businesses.

Job creation

The primary concern with the Start-Up Visa program is its ability to create jobs. Unlike the Federal Entrepreneur Program, which required those coming to Canada to create at least one new job, the Start-Up Visa program doesn’t have job creation requirements in its admission criteria.

Job creation is an important reason why Canada has expanded its pathways to permanent residency. Immigrants with a variety of professional experiences can contribute to Canada’s growing economy, and business immigration plays an important role in that growth.

A 2019 study by Statistics Canada found that immigrant-owned firms had a higher net job growth per firm than firms owned by the Canadian-born. While not all immigrant-owned businesses were founded by immigrants who came through the Federal Entrepreneur Program, they represented about 21 per cent of all immigrant-owned businesses in 2010.

Innovation and internationalization

Aside from job creation, the Start-Up Visa program has additional objectives to boost innovation and internationalization. However, the ability of the Start-Up Visa program to attract businesses that are innovative is still unclear.

Prior to the Start-Up Visa program, immigrant-led businesses in Canada proved to be innovative, although not to the degree suggested by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

A study by Statistics Canada using data from 2011, 2014 and 2017 revealed that immigrant-led businesses operating in Canada for over 20 years were more likely to implement innovations in processes, products or marketing, and use patents compared to similar Canadian-owned firms. This suggests that businesses from the Federal Entrepreneur Program were not necessarily underperforming.

While it’s anticipated that businesses entering through the Start-Up Visa program will exceed these results, the lack of data makes it difficult to determine whether this is actually the case. Only a few applicants were endorsed by investors, and most were supported by incubators, meaning applicants consist primarily of early-stage startups. While they might be innovative, they will likely face challenges in terms of survival and longevity.

While there is no concrete evidence to suggest businesses in the Start-Up Visa program are more innovative, there is evidence to suggest it has resulted in increased internationalization, another one of the program’s objectives. Since the Start-Up Visa was introduced, many immigrant entrepreneurs have moved to Canada from the United States.

Financing constraints and debt obligations

Another area where the Start-Up Visa program falls short is direct foreign investment. While the ministerial instructions governing the program don’t explicitly state capital should only come from Canadian investors, a significant number of designated organizations are based in Canada. This suggests the program is focused on attracting foreign entrepreneurs to Canada, rather than attracting foreign capital.

Without specific requirements, the Start-Up Visa program is unlikely to attract significant foreign capital into the country, as foreign entrepreneurs are often required to secure funds from Canadian investors.

In contrast, foreign entrepreneurs that came through the Federal Entrepreneur Program ended up bringing their own foreign capital with them. The program required these entrepreneurs to have a net worth of at least $300,000. This approach resulted in them being 3.1 to 4.5 percentage points more likely to rely on personal finances and networks to startup their ventures than their Canadian-born counterparts.

Start-Up Visa applicants

In the face of these criticisms, how necessary is the Start-Up Visa program exactly? Aside from instances of fraudulent applications to the Start-Up Visa, there are fundamental issues with the program.

One issue is whether the Start-Up Visa program is diverting potential applicants away from other programs. Another is whether it genuinely offers a route to permanent residency for those who are unlikely to succeed in other pathways.

Foreign entrepreneurs who come through the Start-Up Visa are younger, more highly educated and have better knowledge of English or French than those who came through the Federal Entrepreneur Program.

These characteristics are similar to those arriving through other pathways, with the crucial difference being that Start-Up Visa applicants bring entrepreneurial skills. But these applicants could easily use other routes like Express Entry or Provincial Nominee programs.

In terms of the individual quality of applicants, the Start-Up Visa does not contribute significantly to the skill composition of immigration to Canada. However, it does present an opportunity to invest in foreign startups — all these entrepreneurs need is an ecosystem that will help them thrive. But their prosperity largely depends on Canada’s startup ecosystem, which essentially makes the Start-Up Visa an instrument for investing in risky foreign startups.

So what next?

Whether a policy works depends on its evaluation. The Federal Entrepreneur Program was shut down because many foreign entrepreneurs started small, unscalable businesses, which were deemed unsuitable for Canada’s future economic landscape. However few, these businesses brought in foreign direct investment and created jobs.

As shown by many studies, most startups fail. About half of all startups that have received angel investments fail within five years. At what point do we say that the program may not be working?

Our policy recommendation is that IRCC should conduct a thorough evaluation of the Start-Up Visa program to measure its performance regarding its stated objectives of job creation, innovation and internationalization, as well as provide achievable targets for these objectives.

When IRCC closes a pathway to permanent residency and opens up a new one, Canadians should ask not just whether it aligns with our objectives, but also whether those objectives are clear, measurable goals that can be evaluated over time.

Stein Monteiro receives funding from the Canada Excellence Research Chair in Migration and Integration.

Bradley Bernard receives funding from the Canada Excellence Research Chair in Migration and Integration.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.