"It looks a bit like some sort of fish aggregating device, either that or an out-of-place picnic platform," speculates Phill Sledge of Kaleen, who on a recent sail on Lake George stumbled upon an unexpected site - a rusting platform rising out of the middle of the lake.

With water levels at the enigmatic body of water still hovering around the highest sustained levels recorded in the last 30 years, more adventurers are braving floating logs, semi-submerged fences and fickle winds to explore the 20km-long by 10km-wide lake located 50 kilometres north-east of Canberra.

"With solar lights draped over it, perhaps it's some sort of UFO-landing pad," muses kayaker John Smithers of Kambah, who almost paddled right into the rickety wooden stand midway between Geary's Gap (the Weereewa Rest Area on the Federal Highway) and Rocky Point and the eastern shore (yes, beneath Joe Hockey's much-loved wind turbines).

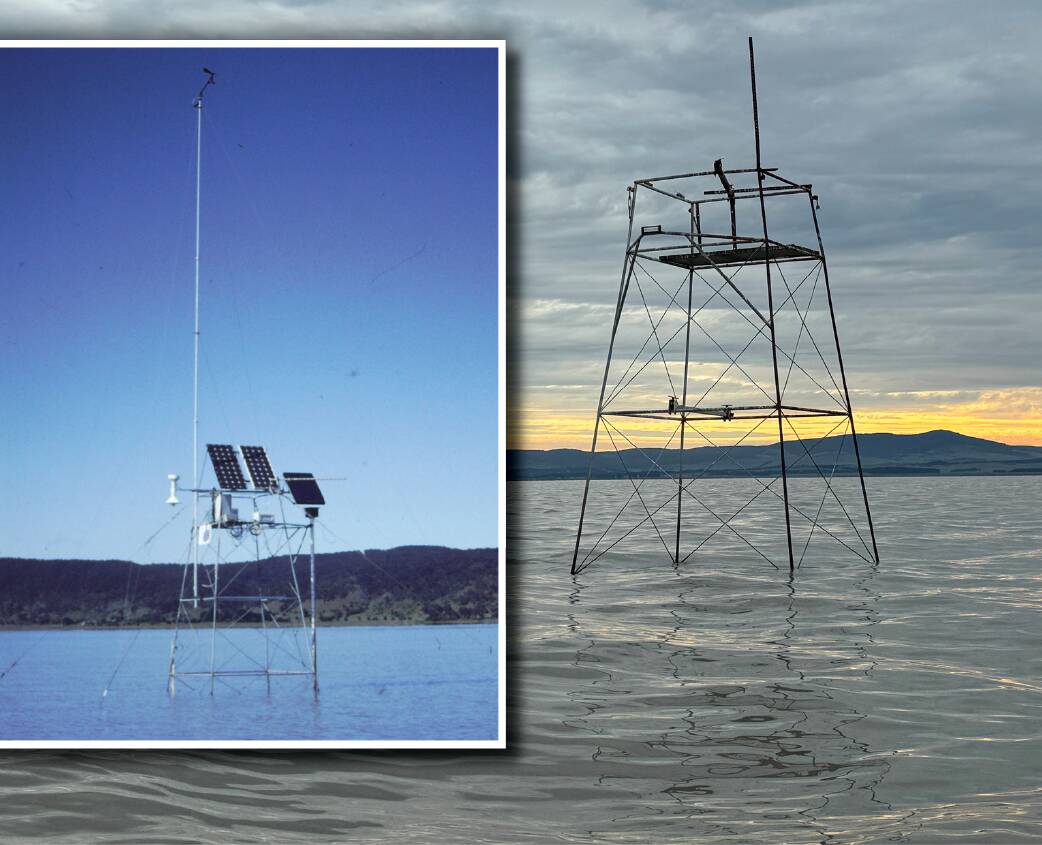

The peculiar platform, its threadbare wooden surface pockmarked with gaping holes, isn't the only curious contraption mystifying kayakers and sailors. A couple of kilometres to the north of the platform is a curious metal tower that at first glance resembles an oversized tennis umpire's chair.

Although the lake has long been a hot spot for ufologists, even when dry it's hardly the place weary intergalactic travellers would stop for a spot of tennis. So, what exactly are the origins of these two strange structures?

Well, it turns out they are both relics from a ground-breaking wave motion study conducted in the early 1990s - the last time the lake was as current levels.

"It's a long time ago, I rarely get questions about it anymore," reports Dr Ian Young who led the study while working at the University of NSW Canberra at the Australian Defence Force Academy.

"The US Navy needed to update their wave models for operations like amphibious landings - and to more accurately predict wave motion in shallow water," recalls Dr Young whose team of four erected a network of eight measurement stations (towers) and one platform (for temporary accommodation) along a 14-kilometre stretch of the north-south axis of the lake.

While Dr Young's research was funded in the order of a relatively meagre $300,000, the US Navy outlaid more than $5 million on a simultaneous experiment at Duck in North Carolina.

"Unfortunately, the American experiment was abandoned after critical equipment sank, so the focus for the entire project quickly turned to Lake George," recalls Dr Young.

By comparison, the Lake George study was a triumph of scientific endeavour.

In fact, according to Dr Young, "Thirty years on, the data from Lake George still forms the basis of almost all global wave models used by meteorological agencies, oil rig designers and many others, including the US Navy." Heck.

Dr Young's basic hypothesis was that as the wind transfers energy to the waves, the waves get steeper until they begin to break through a combination of white-capping and friction with the bottom of the lake.

Now, Lake George afficionados will know these treacherous steep waves have sadly contributed to the deaths of 13 people in boating accidents on the lake since the 1950s, including five Duntroon cadets in 1956.

"So, yes, we had a very good idea of the way the waves behaved before we started, but no one had previously quantified those physical processes," explains Dr Young.

Of course, as with just about anything associated with the ever-changing lake, it wasn't all plain sailing for Dr Young's team.

"Prior to the experiment, we set up an anemometer on the western shore where we observed that the prevailing winds were northerlies or southerlies," explains Dr Young. "It was only after we'd erected the towers on a north-south axis in the middle of the lake that we discovered the prevailing winds away from the shore were actually westerlies and easterlies."

Lake George was up to its old tricks. When an easterly blows towards the western escarpment (which runs above the Federal Highway), the escarpment blocks it, forcing the wind to blow parallel (north-south) to the western shoreline.

As it was critical for the evolution of the waves to be measured from the direction the wind was blowing, this anomaly meant that Dr Young's experiment took three years, much longer than initially anticipated.

"In hindsight, we should have set up the towers on an east/west axis instead," admits Dr Young.

While Dr Young hasn't been out on the lake since his trailblazing experiment, during his term as ANU vice chancellor (2011-16) he "drove past it many times" and is surprised to learn that at least one tower and the platform are still standing.

"When we erected them, they were held down by guy ropes and cables driven deep in the lakebed," he explains. "At the end of the experiment, the farmer who leases the land they are on was happy for us to leave them in situ as they could offer some much-needed shade for his stock when the lake dried out.

"However, thirty years exposed to the elements, they've rusted and collapsed and one by one the towers have fallen over," he explains, adding "it's amazing that without any guy ropes or cables at least one tower and the platform are still standing."

Indeed. Your Akubra-clad columnist can confirm from a visit to both structures earlier this week that even in a gentle breeze, both were swaying. It's only a matter of time before they topple over too.

That is, of course, unless a posse of little green men wielding tennis racquets zoom off with them first.

What's it like to sleep on the lake?

While many of us have driven past it and some have even dipped our big toe in its murky waters, Dr Young and his team are among the few to have bunked down overnight on Lake George.

"Not that we got much sleep," recalls Dr Young who says although the measuring stations perched in the middle of the lake transmitted data in real time to a base station on the western shoreline, "occasionally we needed to be on site to conduct a specific experiment".

"Invariable those nights were in winter when the wind was blowing a gale," he explains "Even though we had a small shed to shelter in, it was bloody cold and not very pleasant on that platform." I bet.

But while Dr Young's teeth still chatter at the thought of those frigid nights, it's Louis Verhagen, a PhD student who was working with him at the time, that he really felt for.

"Poor Louis spent many a day in a dry suit freezing his rear end off in the water with zero visibility while attaching equipment shackles to the base of the platform and towers," reveals Dr Young. "Not only did he have to dive into the water, but he also had to take off his gloves to screw on the tackle." Brrr.

The most memorable moment during the two-year research project came when Dr Young and his team were transporting equipment out to the site via a large flat-bottomed punt.

"On this particularly windy day, the nose of the punt came over the top of a wave and as it ploughed straight into the front of the next wave, it kept going down... and down," recalls Dr Young. "We all fell silent, wondering if the nose would ever come back up, which eventually very slowly it did. We then furiously started to bail the water."

WHERE IN THE REGION?

Rating: Medium

Clue: Not far from a "mysterious" lake

How to enter: Email your guess along with your name and address to tym@iinet.net.au. The first correct email sent after 10am, Saturday March 9 wins a double pass to Dendy, the Home of Quality Cinema.

Last week: Congratulations to Toni Hogan of Bonython who was the first reader to correctly identify last week's circa-1924 photo as an aerial view of Reid/Braddon and beyond with the demolished St John's Rectory 'Glebe House' (grounds of which now form Glebe Park in Reid) at the centre bottom, Gorman House centre right, and the former railway line curving along the former Railway Reserve to its terminus near current-day Lonsdale Street.

Toni just beat several readers, including Leigh Palmer of Isaacs and Conrad Burden. Roy Jordan reports he lives on Amaroo Street, Reid, which runs parallel to the old railway line. "I walk along the route of the old railway track (now disappeared) through Glebe Park into Civic on most days," he reports.

On Terra firma

Several years after his 1992-93 research, Dr Young conducted further wave studies at Lake George. Unlike his earlier experiments, this study could not be run remotely and so a platform erected on the eastern side of the lake was connected to the shore via a 40-metre-long elevated walkway. "It meant we didn't need to get into the water," explains Dr Young. All that remains now is a dilapidated shed on the shore.

Disappearing act

Lake George has a reputation for untimely filling and evaporating. For example, in the 1930s a land-speed record attempt on the dry lakebed was abandoned after heavy rains started to fill the lake. However, for Dr Young's team the reappearance of water in the lake in the early 1990s was a godsend. "As Lake George was dry in the years leading up to our experiment, we'd originally planned to undertake it at Lake Alexandrina in South Australia," he explains. "But it ended up being much easier to conduct at a 'full' Lake George due to a much lower level of recreational boating activity to work around."

In fact, during the two years of his first Lake George study, Dr Young only saw another boat once - water police investigating the disappearance of two Canberra fishermen after their capsized dingy was found 100 metres from the eastern shore in August 1992. Sadly, the bodies of the two men were found about five kilometres apart several weeks later.

- CONTACT TIM: Email: tym@iinet.net.au or Twitter: @TimYowie or write c/- The Canberra Times, GPO Box 606, Civic, ACT, 2601