By the summer of 1986, it seemed there was no end to Queen’s omnipotence. Rallied by their show-stealing set at the previous year’s Live Aid, the band now saw promoter Harvey Goldsmith swamped with bookings for their twin shows at Wembley Stadium.

A further two 35,000-capacity dates in Newcastle and Manchester were added as a release valve, to no avail. “They literally sold out in two hours flat,” noted Goldsmith at the time. “So we’ve added one huge show at the end of the Magic Tour at Knebworth Park. We have a capacity there of 120,000 – and on the first day of tickets going onsale, we sold 30,000 tickets. They seem to have an endless market.”

But if you squinted a little harder, moved quietly amongst the band’s inner circle, the first hints of Queen’s demise were already tainting this apparent purple patch. Though he would not officially learn of his AIDS diagnosis until the following year, an aside from Freddie Mercury in Budapest, just two weeks before Knebworth, was pure gallows humour, the singer telling a reporter that he would return to play the city’s Népstadion “if I’m still alive”.

Then there was the throwaway remark, overheard by Brian May in Spain and quickly discounted: “John and Freddie were having a minor disagreement. And Freddie said, ‘Well, I won’t always be here to do this…’”

Whether Mercury sensed the gathering storm or merely wished to avoid the embarrassment of treading the boards as a middle-aged rock star – “I know there’ll be a time when I can’t run around onstage because it’ll be ridiculous” – going out with a whimper wasn’t Queen’s style. Capping a Magic Tour that in total grossed £11 million, played to 400,000 fans and, in Roger Taylor’s words, “made Ben Hur look like The Muppets”, Knebworth was grandiose in every sense.

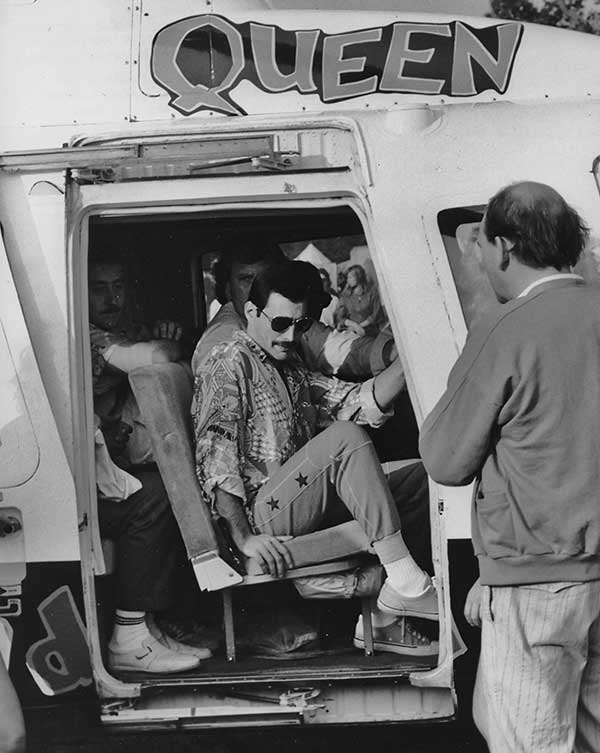

Over 120,000 punters flooded the gardens of the Hertfordshire country house. A battalion of amps, eight miles of cabling and a twenty-foot video screen kept an army of techs and roadies busy. With suitable pomp and pageantry, the band themselves arrived in the gaudy ‘Magic Helicopter’, personalised with the art from that year’s A Kind Of Magic album.

That night’s set was a masterclass, roaring to life with the post-Live Aid single One Vision, mining every corner of the catalogue and sweeping up hits from Under Pressure and Another One Bites The Dust to Bohemian Rhapsody and Crazy Little Thing Called Love. But maddeningly, given the significance it would later take on, the show was never captured for posterity.

“Can you believe that on Freddie Mercury’s last concert, the great showman, no one actually pressed record?” gaped Knebworth House’s current occupant, Henry Lytton-Cobbold, who watched the concert as a twenty-something. “There’s a Dutch bootleg of somebody filming a screen at the back of the audience for the whole show, so there’s a record of it, but no proper film.”

There were further frustrations afoot, the normally mild-mannered Deacon smashing his bass into his amp after Radio Ga Ga. “He wasn’t pissed off at his gear, he wasn’t pissed off at me, I don’t know what it was,” recalled roadie Peter Hince. “John acted strangely on that tour; he was doing stuff that was out of character.”

While there was a familiar flourish to the encore of God Save The Queen – Mercury resplendent in crown and gown, bidding the crowd “goodnight and sweet dreams” – the band came offstage to find hairline cracks in their empire. The triumph of the night was soured by black news, the band learning that a 21-year-old fan had been fatally stabbed in the melee, with medics unable to reach him.

As for Mercury, the singer barely stopped to enjoy the backstage bacchanals before flying home to London. “Did we know it would be the last time?” May pondered in Guitar World. “No. Freddie said something like, ‘Oh, I can’t fucking do this anymore, my whole body’s wracked with pain!’ But he normally said things like that at the end of a tour, so I don’t think we took it seriously, really.”

But soon, it was hard to ignore the mounting evidence that Queen – as a live entity, at least – was running out of time. Returning from a holiday in Japan, Mercury was confronted by a tabloid feeding frenzy, The News Of The World reporting a secret AIDS test in Harley Street, while The Sun went with the screamer headline: ‘Do I Look Like I’m Dying Of AIDS? fumes Freddie’. The article went on to quote the singer as saying he was “perfectly fit and healthy”.

But in the words of his flamboyant 1987 solo hit, rock’s best frontman was also a great pretender. He was five years from death – and had sung with Queen for the final time.