One of the best jokes in all of science fiction posits that dolphins are messing with us. In Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, we learn, right before the Earth’s destruction that dolphins are hyper-intelligent, and send humanity one last message before departing our planet: So long and thanks for all the fish. The problem is, of course, that regular folks didn’t get the message because we don’t have any technology to communicate with whales, dolphins, or other sea creatures with very large brains. At least not yet.

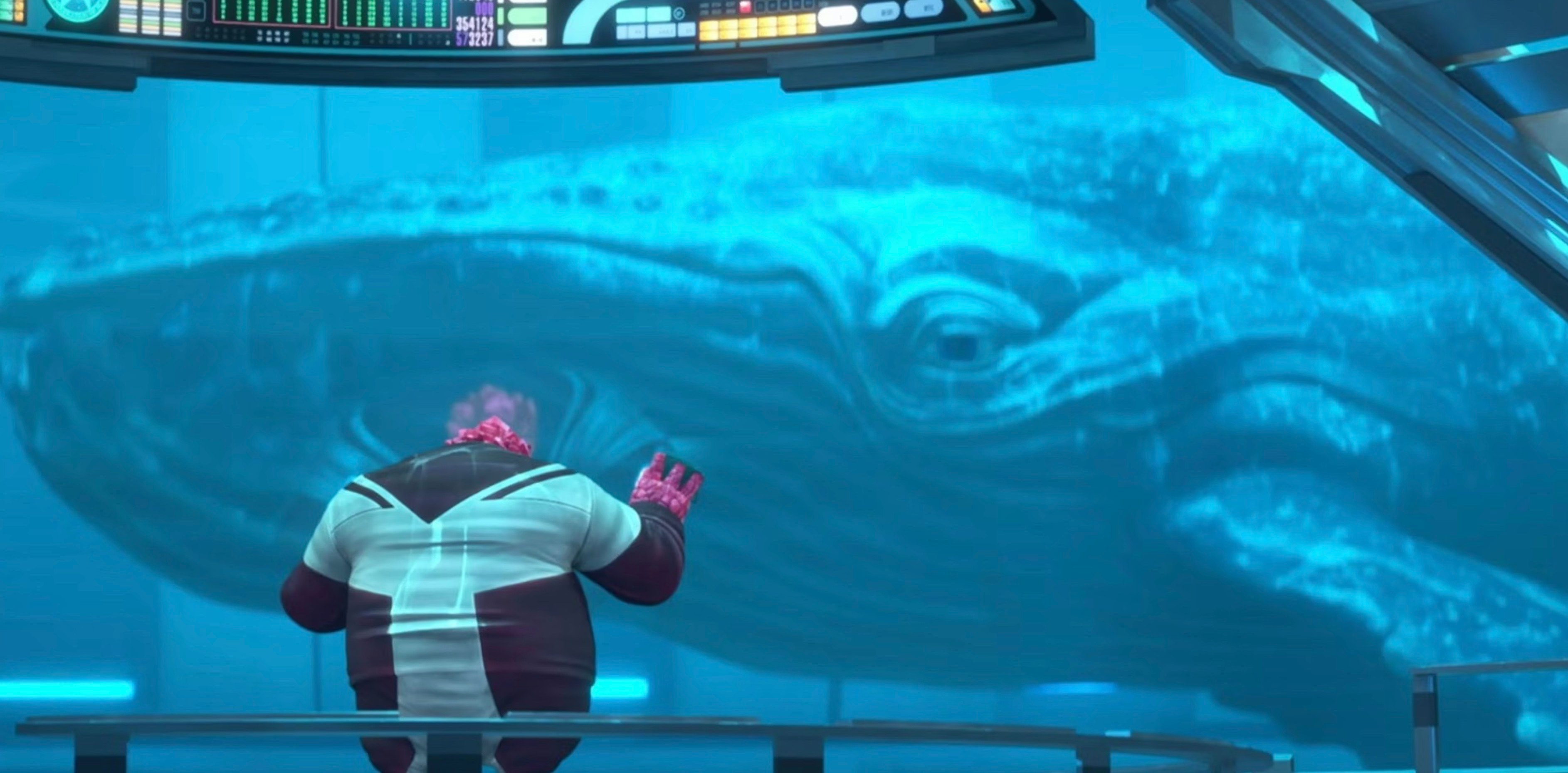

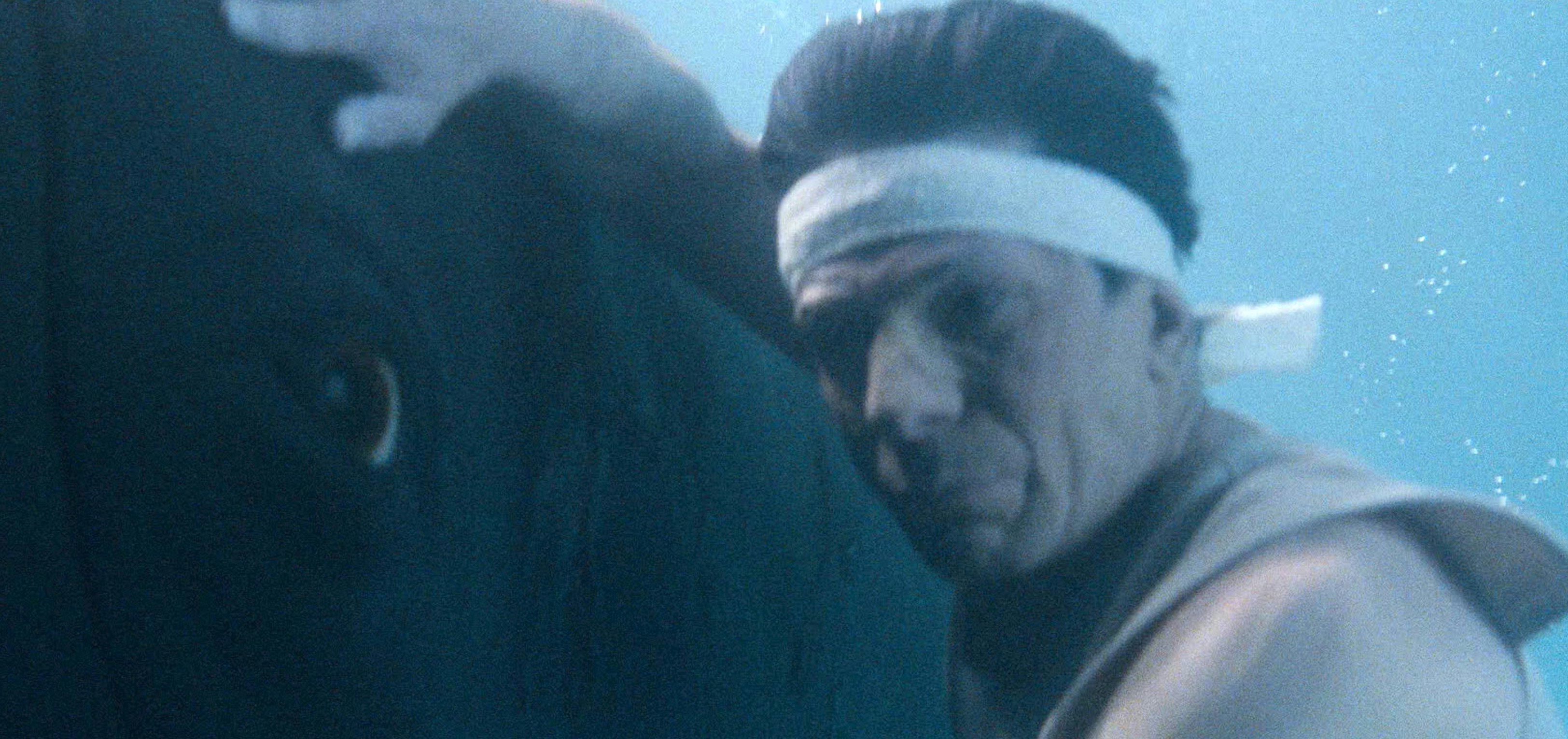

In a lot of popular science fiction — most notably, the Star Trek franchise — methods exist to translate the language of whales, dolphins, and other sea life into English. In fact, the entirety of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) is predicated on the idea that ancient aliens communicated with humpback whales through whale song. Fast-forward to 2024’s Netflix’s Season 2 of Star Trek: Prodigy (not to mention Lower Decks Season 3 in 2022) and Starfleet folks can now talk to whales, dolphins, and all sorts of undersea life through their handy universal translator. But will we ever get there in real life?

The connection between de-coding whale speak and talking to aliens isn’t as far-fetched as it might sound. Right now, SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) researchers like Josie Hubbard of UC Davis are taking part in whale expeditions to decipher language. In a BBC article this year, Hubbard noted that whale song is “like experiencing another world.”

The notion that whales have a complex language just outside of human perception has deep roots in both marine biology and language studies more broadly. In 2023, Oceanographer David Gruber — who studies sperm whale vocalizations — equated studying the language of whales to the premise of a far-out science fiction movie. “It’s almost like Arrival,” Gruber said in a Daily Beast article last year, referencing the acclaimed Denis Villeneuve film in which a scientist (Amy Adams) attempts to communicate with tentacled aliens. But, in order to create reliable translation technology — like the kind recently featured in Star Trek: Prodigy — Gruber notes that the challenge is a steep one. “Basically, we need to train the computer to be a baby whale,” he said.

Dr. Brenda McCowan, who took part in a groundbreaking 2021 SETI project in which a humpback whale named Twain “conversed” with the crew, agrees that a computer is essential. “A big challenge for us is classifying those signals and determining their context, so we can ascertain meaning,” McCowan told the BBC. “I think AI will help us do that.” The result of this looks like a page out of Star Trek, where everyone appears to speak English most of the time, while the algorithmic universal translator does all the work.

This all helped inspire astrophysicist and resident science advisor for the entire Star Trek franchise, Dr. Erin Macdonald. For Trek, Macdonald was focused on how such research could lead to the moment that Prodigy and Lower Decks depict — not just talking to whales, but having them in their own navigation center on a starship, called Cetacean Ops, a place where the whale assist the crew in astronavigation. “We always put it in our own reference frame,” says McDonald. “But now, it’s like, we don’t have to communicate the same way. They don't have to be talking to each other in the same way that we are talking to each other. And I think that progress does extend toward an idea like the universal translator [in Star Trek].”

“Most organisms simply have no need to communicate anything more complicated ... than ‘Watch out there’s a predator!’ or, ‘Wanna mate?’”

And yet, there is a paradox central to all of this aspirational thinking. We’re assuming that the language of animals has complex parallels to our own language, mostly for the sake of making the argument. As Dr. David Shiffman — a marine biologist who studies sharks — tells Inverse: “Most organisms simply have no need to communicate anything more complicated to another member of their species than ‘Watch out there’s a predator!’ or, ‘Wanna mate?’”

In this way, scientists like Shiffman are skeptical if technology could offer any meaningful way of sharing ideas. From Shiffman’s point of view, if the communication between organisms of the same species is already fairly spartan, then it follows that they have even less time for different species.

McGowan has expressed similar skepticism, saying we shouldn’t be “focused on humans trying to understand whales. But how to understand how whales are talking to each other.”

“Most organisms have no need to communicate anything to a member of another species more complicated than ‘hey you’re getting pretty close to my offspring there, back off.’” adds Shiffman. “It’s not just a matter of speaking a different language.”

Still, in the realm of science fiction, it’s more fun to imagine a scenario in which whales or other marine life would want to talk to us. In The Voyage Home, Spock reminds us that it is possible to replicate the sounds of humpback whales, but because Vulcans and humans don’t know the language “We would be responding in gibberish.” Handily, Spock is able to bridge this gap with the telepathic mind-meld, something that would instantly answer all of these questions.

Right now, without a universal translator, we can keep trying talk to whales and dolphins. The question is, do they want to listen to us? Hopefully, it won’t take the destruction of the entire Earth to find out.