Vanessa Bradley was no stranger to hurricanes. Bruising fall storms were a regular occurrence in South Carolina, where she and her wife, Evelyn, lived before moving to Prince Edward Island in 2020. When a monster hurricane named Fiona began tracking toward PEI last September, she and Evelyn remained calm. They reviewed their emergency plan. They stocked up on canned beans and smoked sausages. They dragged their mattress from their bedroom out into the living room, where there was less danger of a large window blowing in.

Out in rural Blooming Point, at her picturesque property on the northern shore of PEI, Debbie Langston followed the instructions provided by the provincial Emergency Measures Organization (EMO): storing extra water, filling the gas tank, making sure to have cash on hand. She moved her vehicles to a large field, away from the risk of falling trees.

Jim Randall wasn’t too worried about his family’s cottage in the low-lying Hebrides community, an ocean-facing peninsula along North Shore. It had been damaged by flooding during the post-tropical storm Dorian in 2019, and he’d paid $14,000 to raise the cottage by three feet as a hedge against future storm surges. The contractor had assured him he’d never have to worry about flooding again.

In Charlottetown, Tessa Rogers worked with some of the city’s marginalized residents, including community members who slept rough most nights. At the time, Rogers was the street outreach coordinator for PEERS Alliance (where Bradley was also on staff). She alerted the residents of a tent encampment in the city’s downtown core about an emergency shelter the province had set up just before Fiona was supposed to hit. In a scramble for time, Rogers and her colleagues told their clients that the shelter was in their best interests—though she soon found out that they would not have access to a working backup generator and no way to contact emergency services should landlines or cellphone services fail.

On September 22, the Canadian Hurricane Centre (CHC) was forecasting gusts up to and even more than 140 kilometres per hour, offshore waves ten to twelve metres high, and significant rainfall. At the province’s final EMO briefing, livestreamed at 1:15 p.m. on September 23, a clearly anxious Darlene Compton, then minister of justice and public safety, did her best to look battle ready. Fiona, just a few hours away by that point, was shaping up to be one of the most powerful storms in Canadian history. Compton urged Islanders to report storm damage online and to call 911 in the event of an emergency—despite the extreme risk of widespread power outages and the fact that telecommunication networks had been unreliable during previous storms.

At the same briefing, Tanya Mullally, the EMO’s emergency management coordinator—who, at the time, served as the acting director of public safety for the province—urged residents in low-lying areas to consider seeking higher ground. “Retreat indoors,” she said to Islanders at large. “Keep your families safe. We will kind of, I guess, see you on the other side of this.”

Like many islanders, my partner and I spent the night of Friday, September 23, sheltered in a corner of our basement, listening to shrieking wind, the constant crack of splitting trees, the sickening rip of metal from the house. We live next to a number of towering poplar trees, which, on a fine summer’s day, shelter any number of starlings and blue jays as well as the occasional bald eagle. During the storm, these gorgeous giants—still covered in their heavy green foliage—became instant liabilities. We kept anticipating the moment we’d hear one of the trees come crashing through our roof.

As the storm intensified, Bradley was at home monitoring her social media feeds. A friend’s bedroom window had blown in. Glass balconies on the building across the street shattered and collapsed. She and Evelyn huddled together in the living room, without power, worried that the skylight in the next room would be sucked out by the storm.

When dawn arrived in Blooming Point, winds were still gusting up to 150 kilometres per hour. Langston got a peek of the destruction. “When we opened the blinds, it was just absolute devastation,” she says. Hundreds of trees were down, including over twenty that were now blocking her driveway. “We’ve been here for eighteen years. There would have been trees that have grown up as our kids have grown.”

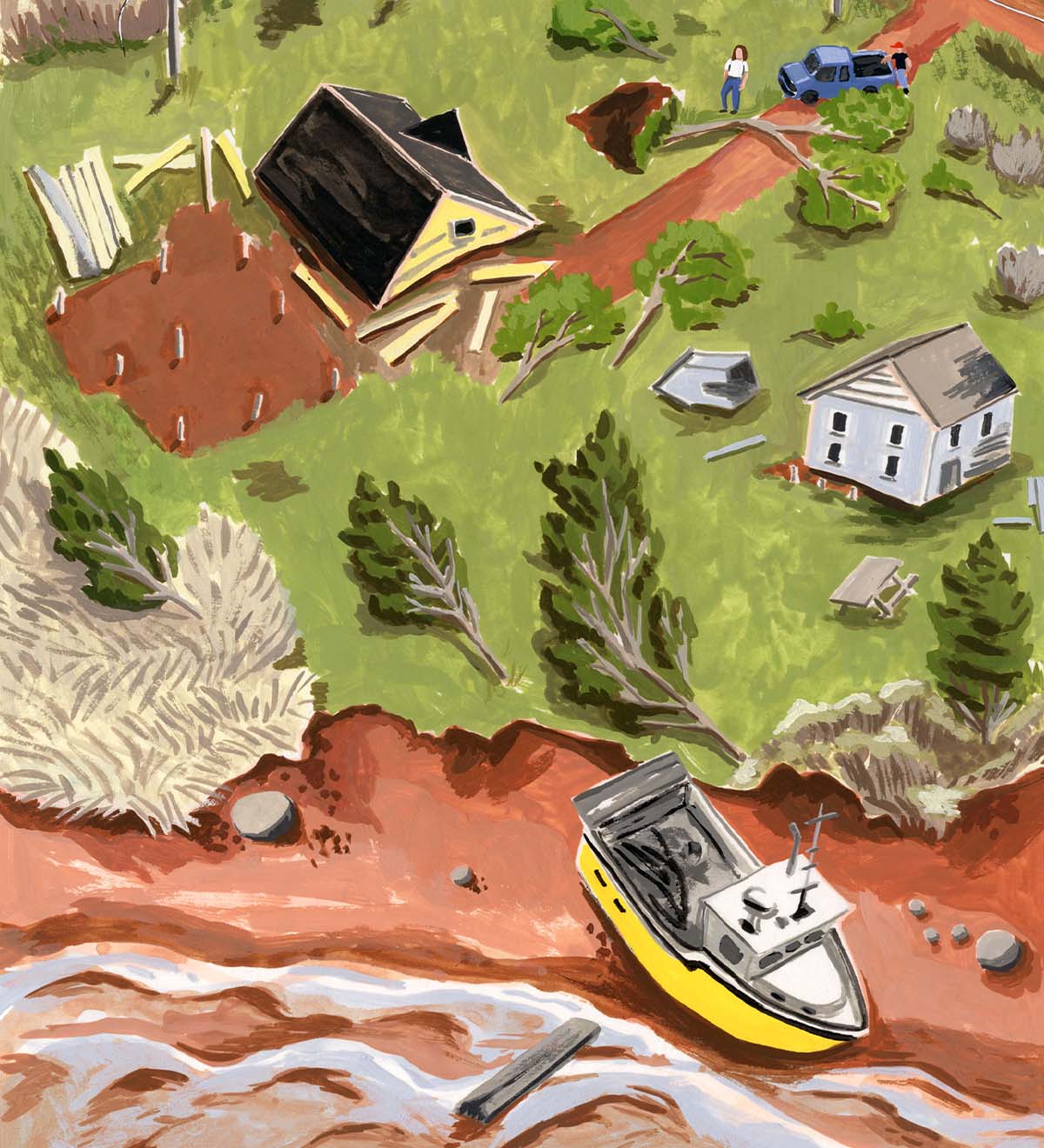

Randall received a call from a friend over the weekend, telling him his cottage had disappeared. “Only when I went up on Sunday did I realize that the second floor of our cottage still existed,” he says, “but it was sitting on the edge of a causeway about 400 metres away from where our footings were. The bottom floor was missing.”

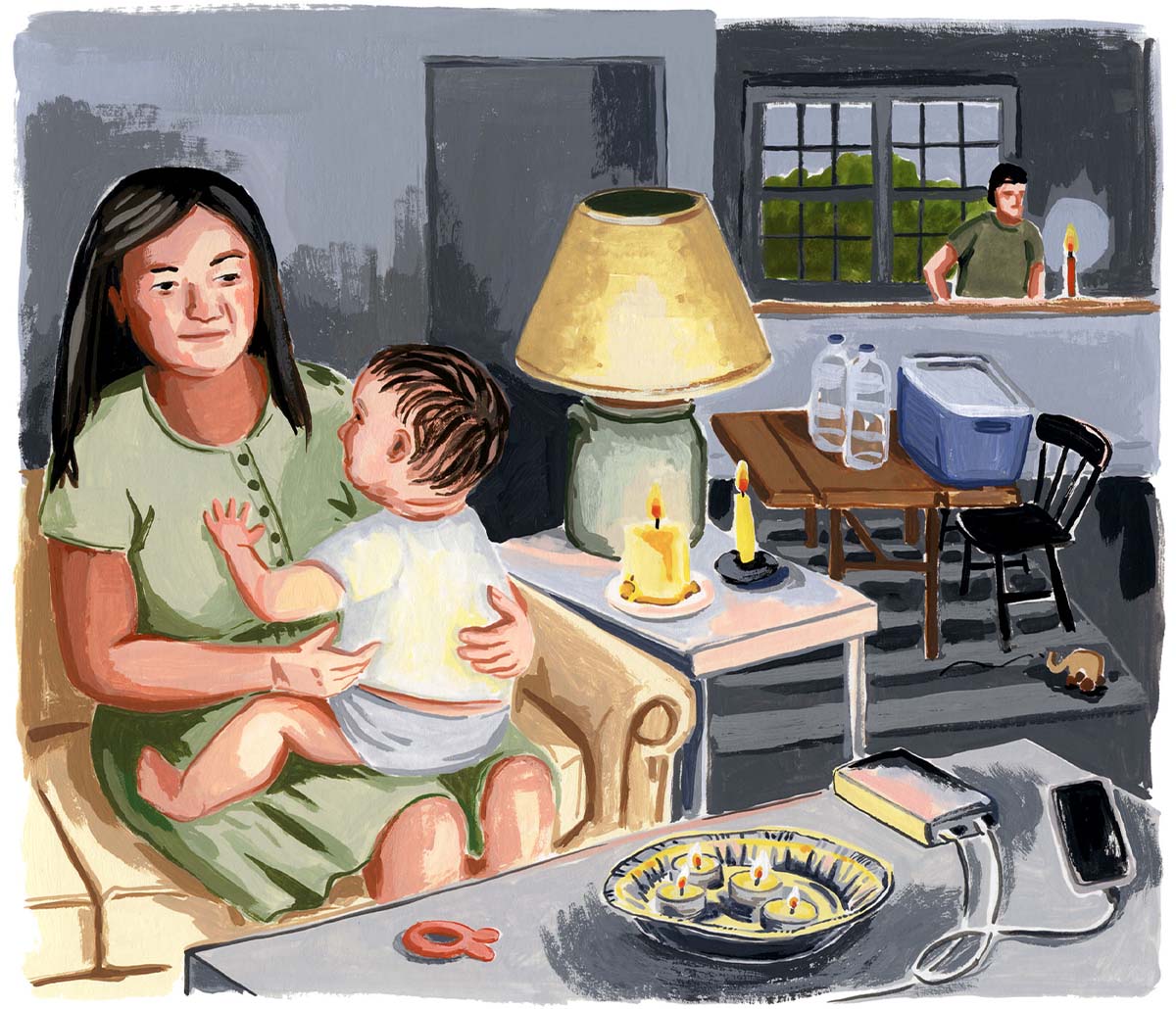

In Charlottetown, the emergency shelter where Rogers worked was nearly full, and the power was out. There was no fuel for the backup generator. She and other staff had to rely on their own flashlights and headlamps to escort agitated clients to the bathroom. Some of her regular clients were substance users who needed medication that could be dispensed only in daily dosages by a pharmacy. At least one person began to show signs of active withdrawal. Tensions were running high. With power out and cellphone services down, there was no way to reach emergency personnel should things escalate. “If anything happens, who has communication methods?” she remembers thinking to herself. “Because we don’t right now.”

As dramatic footage of devastated coastal communities dominated national news in the days after Fiona hit, debates began to rage about who should be accountable for securing Islanders and their properties from the impact of extreme weather. The government had been announcing for days that a so-called storm of the century was likely to strike the Island. Why wasn’t the province more prepared?

Even as they hunkered down to wait for Fiona, some Islanders were still recovering from Hurricane Dorian. The 2019 storm had knocked out power to nearly 80 percent of Island homes. It left fishing boats swamped, crops trampled, houses and cottages damaged. Some communities went without internet, landline, or cellphone coverage for extended periods, meaning they couldn’t reach emergency services. Some families in low-lying areas had to be evacuated from flooding. The damage to insured property was estimated at $17.5 million.

In Dorian’s aftermath, the provincial government engaged a consulting group to review its emergency efforts. The so-called Calian report pointed to insufficient staffing, inadequate equipment, poor communication, and a lack of adequate training among some provincial employees and emergency response workers as the reasons why the government hadn’t provided a more robust response. The report recommended, among other measures, that key emergency personnel adopt alternative communication methods, like a backup radio system, to be used in the event of power outages. It also said the government should provide clearer timelines to residents for when power would be restored and noted the need for more resources for checking in with vulnerable populations. It remains unclear whether the government adopted any of those recommendations in time for Fiona.

In an interview, Mullally says Dorian became an important reference point for the EMO’s plan to communicate with Islanders about Fiona’s potential damage. “We did say this could be as bad, if not worse,” she says. “We did speak to the historical significance of the storm surge being forecasted. So we were clear of what the potential impacts were.” But it’s not always obvious how being informed of what’s to come translates into being ready for it.

The wind and rain began to settle late in the day Saturday, September 24. By then, the scale of Fiona’s devastation had started to filter through on social media—at least for the lucky few with service, data, and access to power. Premier Dennis King, ashen faced and looking overwhelmed, said the destruction was “beyond anything that we have witnessed before” but that Islanders should “count our blessings large and small” that there were no reports of significant injuries or worse. But there were disruptions to cellphone and landline services, making it difficult for some to contact 911. Without a backup generator, the province’s only major fuel terminal was unable to distribute gasoline, and lines soon grew massive at the few stations open.

By Sunday, the day after the storm, emergency reception centres began to pop up across the province to provide food, heat, and shelter to the displaced, though the recommendations to shelter in place remained in effect. In any case, many residents were barricaded in their homes by fallen trees and downed electrical wires. Islanders turned to live coverage from the CBC via battery-operated or hand-crank radios, though even CBC PEI was off the air in the first hours of the storm, going eerily silent until the national broadcaster was able to patch in rotating service from studios in Moncton and Halifax. Over 95 percent of the province would lose power, in some cases for three weeks. The provincial utility, Maritime Electric, came under intense criticism for being slow in restoring power and its failure to provide clear timelines early on.

It’s hard to accurately describe the sense of isolation and the deep unknown as we tried to cope without power, the nights growing colder and darker as scant information filtered in over the radio. I remember driving to the hockey rink of a nearby community to charge my phone, afraid of wasting our precious supply of gas by venturing too far.

Langston and her family went without power for nineteen days. If you live in a rural community, no power means you can’t pump your well. Without access to running water, Langston relied on daily sponge baths and occasionally showered at the homes of friends. She used water stored in her hot tub to flush her toilet—

until that supply also ran out. She’d wait for daylight to arrive so she could apply makeup in front of her car mirror and would try to find a corner in a local school where she could connect virtually to work. Filling up plastic water bottles and receptacles at friends’ and neighbours’ homes became routine, as did cooking family meals over a small propane stove.

Across the Island, scores of schools were damaged, fishing wharves like Red Head Harbour virtually obliterated, bridges rendered impassable, and private homes and cottages destroyed. The overall damage wrought by Fiona in the region was estimated at $800 million, making it Atlantic Canada’s costliest weather

event and one of the most expensive in Canadian history.

Not far from Langston, a powerful storm surge of over two metres devastated the fragile barrier dune system along the North Shore. Between three and ten metres of coastline eroded within PEI National Park alone. Many of the Island’s iconic white sand dunes were sucked back into the ocean or severely damaged—along with campground sites, footbridges, walking and cycling trails, and even roadways.

Those same Instagram-worthy sand dunes and red shorelines draw millions of tourists to the province’s pristine beaches each year. As a low-lying, crescent-shaped sandbar set in the tempestuous Gulf of St. Lawrence, PEI is especially vulnerable to howling winter gales and raucous storms. The ecologically protective feature of the dunes underscores a deeply uncomfortable existential truth: the Island is gradually shrinking.

“PEI is very unique in terms of its landscape, because it’s so fragile,” says Xander Wang, associate professor at the University of Prince Edward Island School of Climate Change and Adaptation. “We don’t have this hard rock to protect it.” Unlike the granite coasts of neighbouring Nova Scotia, PEI is prone to extreme coastal erosion, magnified by rising sea levels. And at current erosion rates, which are thought to average nearly thirty centimetres per year, an estimated 1,000 structures on PEI—homes, cottages, and businesses—might fall into the sea by the end of this century.

Scientists say climate change will worsen the impact of storms in Atlantic Canada. For one thing, warmer water can lead to higher wind speeds, creating more intense and, in some cases, slower-moving storms. “They don’t move quite as fast, and it tends to be a more meandering path,” says Chris Fogarty, a meteorologist at the CHC. The warming of the polar regions in particular has a direct effect on the paths of storms like Fiona. As the storms stall, rainfall accumulates quickly, increasing the potential for catastrophic flooding.

Low atmospheric pressure at the eye of a storm produces more intense conditions; Fiona’s pressure was among the lowest ever recorded in Canada. It also merged with a cold air mass from the north, magnifying its severity. “Fiona was not purely hurricane,” says Fogarty. “It had the power and vigour of a hurricane from the warm air and moisture from the tropics, but it also grabbed this energy from the colder air mass from Quebec.” The clash of the two systems made Fiona’s behaviour more severe. And it offered a disturbing taste of what’s becoming ever more common.

Canada has the longest coastline of any country in the world, and both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts will feel the impact from rising seas. In PEI, sea level rise leading to higher waves—coupled with human activity, like increased cottage development close to the shore—means even a typical seasonal storm will produce more damage than in the past.

Over the last year, the PEI and federal governments have introduced their respective climate adaptation plans, both of which call for building capacity for “disaster resilience” and protecting natural coastal assets. The provincial plan includes developing a coastal flood warning system that will alert communities and residents in real time, on various platforms, about the potential risk to coastal activity and infrastructure. The province’s Coastal Hazards Information Platform (CHIP) now provides detailed maps of regions and specific properties at risk of coastal flooding. All of this knowledge means policy makers and residents alike possess a clear road map for curtailing, to some extent, the damage associated with storms like Fiona.

But exactly who is responsible for implementing climate adaptation measures is a complicated question. A fishing harbour may be managed by the federal government, while protecting the nearby coastline is the responsibility of the province. Adapting the roads fishers use to access their boats may fall under municipal control. Finger pointing between various levels of government and wrangling over funding can bog down planning and stymie the far-reaching changes experts say are needed to protect lives, natural assets, and property from future risk. Of all the challenges ahead, this might be the most daunting one.

aday after Fiona struck PEI, a shaken Premier King asked the federal government for support. Within days, the Canadian military had a hundred soldiers on the ground to help clear fallen trees and repair key infrastructure. The Canadian Red Cross and a handful of non-governmental organizations set up operations to provide food and funnel donations to communities. Yet frustrations with ongoing outages and the slow pace of government efforts, including the rollout of immediate financial aid, mounted. The provincial government made an initial cheque of $250 available per eligible resident, to be administered through the Red Cross, though even this simple gesture turned into a logistical nightmare. Many residents with limited means had to drive for up to an hour to wait in daylong queues to register for the funding, with no guarantee they’d even see a Red Cross representative. Stories of people turned away abounded. Rogers tried to help her clients access aid by vouching for those without formal identification. She was finally able to secure a pop-up event for her clients with Red Cross staff in November, nearly six weeks after the storm, but only because she managed to track down a Red Cross employee via LinkedIn.

In the immediate aftermath of the storm, many Islanders stepped up. One group formed an organization called Charlottetown Mutual Aid, which cooked hot meals; collected donations of clothes, tents, and food; and helped funnel direct financial aid to those most in need across the city, including seniors, students, and people experiencing homelessness.

But stories of those left to fend for themselves also emerged. A community of seniors in Charlottetown was left shivering in the dark for over ten days in their government-owned seniors complex. When the generator in their building failed, residents were forced to huddle under blankets to keep warm. At another home, at least six seniors experienced falls during periods of extended darkness.

Mullally, who served as the face of the government in daily briefings, praised the efforts of the Islanders and communities coming together after the storm. At the same time, she later told me, in any emergency, Islanders need to learn to plan for themselves and their families.

“As individuals, we need to know what our risks are. We need to determine how to best prepare for ourselves,” she says. “Personally, I had the benefit of a generator in my home. But I still have to plan and I still have to prepare because a generator may not come on.”

Mullally and others working in emergency response believe there’s a window of about six months following a disaster to effect cultural change within the sector, after which time memories—and interest—begin to fade. Her office needs more resources to proactively engage with Islanders about emergency planning, she says, and it needs to coordinate more efficiently with partner organizations—like NGOs, government departments, utilities, and local municipalities—many of which use wildly different IT and database systems. As of mid-July, the most recent update to the PEI All Hazards Emergency Plan is from 2021. All this means that nearly a year after Fiona, the provincial government still doesn’t seem to have figured out how it will tackle the next inevitable large-scale disaster.

Last November, King’s Progressive Conservative government voted down calls led by then opposition leader Peter Bevan-Baker for a full public inquiry into the government’s response to the storm. “Without the ability to compel documents and subpoena witnesses,” says Bevan-Baker, the province’s Green Party leader at the time, “we’ll never know exactly what went wrong, and how we could learn from it for next time.”

“In so many ways, we’ve lost some of our innocence because of what we went through with Hurricane Fiona,” King said in a statement emailed to The Walrus. “Our landscapes have changed, our perspective has changed, and it’s no surprise that our approach to future weather events has to change as well.” The province, he added, has commissioned Dave Poirier, a former chief of police, to conduct a third-party review of its response efforts; as of this writing, the results are expected in time for this year’s hurricane season. The government has also directed more funding to the EMO office to help “adequately plan and strengthen response efforts for future emergencies.”

But many of those I spoke with are still not confident that the province will be ready for the next storm.

In the Netherlands, the government has poured billions into defending low-lying coastlines from flooding. England has designated shoreline management “cells” or regions that employ adaptation methods tailored to local circumstances, such as retreating from the coast in less populated areas. In Canada, we’ve barely begun the conversation around what it looks like to manage coastlines against rising sea levels, says Joanna Eyquem, a climate adaptation expert at the University of Waterloo, who authored a study looking at climate adaptation models around the world. All provinces and territories have now signed on to the National Adaptation Strategy, a federal plan to build climate resilience across the country, which was released with great fanfare last year. It comes with $2 billion in funding to help protect infrastructure and prepare communities for climate change, but experts say the amount is well below what is needed given the herculean tasks ahead. And while the plan earmarks an additional $530 million for a Green Municipal Fund so cities and smaller communities can launch local adaptation projects, some believe that we need to think bigger.

In PEI, an estimated 90 percent of the Island’s total land area falls outside municipal planning regulations. This means residents in unincorporated rural areas enjoy the relative freedom to develop their properties as they please, even if such development puts the property or nature at risk. As one example: coastal residents often “armour” the coast by importing rock from the mainland or depositing recycled concrete at the base of cliffs to delay erosion, though the provincial government has recently announced a moratorium on this practice while it ponders new regulations.

Hope Parnham, a landscape architect and a planner doing research into shoreline erosion on PEI, says armouring is countereffective. While it might protect a sliver of land in the short term, over the medium term, it undermines neighbouring properties and disrupts the overall integrity of the coastline. And while the province maintains a “buffer zone” regulating development within fifteen metres of inland or coastal shorelines, Parnham says exceptions are made on a regular basis.

Over the past fifty years, there have been repeated calls for province-wide legislation to regulate land use, including development in sensitive coastal areas. But such a plan, says Parnham, is still at least a few years away. Meanwhile, with a booming population, the province faces an acute housing shortage, which is why some Islanders will likely continue to build outside municipal boundaries—on lots along highways, carved from prime agricultural land, or along sensitive and eroding coastlines.

Parks Canada staff on pei recently announced their adaptation plans, which include a managed retreat from coastal areas in PEI National Park that were damaged by Fiona. This doesn’t mean that millions of visitors will lose access to the Island’s beloved beaches. It does mean that certain assets (a paved causeway, for example) will be removed or adjusted to adapt to erosion and future storm surges. Some park infrastructure—like modular bunkies or cabins—will be dynamically flexible, able to be moved back when storms approach and as the coastline continues to retreat naturally.

The term “managed retreat” can often invoke the spectre of entire communities being moved or abandoned, but Parnham says it usually occurs one property at a time and can happen as people naturally age out of their homes. Several climate researchers I spoke to believe this type of managed retreat may be the only option for certain properties most at risk. The approach is favoured by climate adaptation specialists like Eyquem who argue for the need to work with nature’s cycles. Nature-based protection—such as introducing natural wetlands or planting intertidal reefs—can better absorb the energy of powerful waves and slow down the impacts of erosion.

But the question of who should finance this kind of work or compensate homeowners is far from settled. Most insurance companies do not currently cover losses incurred by coastal storm surges. Seasonal homeowners are not eligible for federal or provincial Fiona disaster recovery programs, which means Randall will receive no compensation for his cottage, a major asset he and his family had hoped to pass on to the next generation. He now owns an empty plot in a floodplain; it’s hard to even guess at the property’s value.

While he applauds the provincial government’s focus on climate adaptation efforts, he would like to see funding available to buy out owners whose properties are at high risk of flooding—or perhaps subsidies for climate adaptation efforts, like lifting properties onto posts so they can better withstand future storm surges.

Eyquem has a different take. She believes the greater burden for protection and adaptation in cases like Randall’s should rest on the individual property owner. In most cases, disaster relief programs currently provide financial aid to uninsured homeowners, some of whom may have willingly built homes in high-risk areas.

“I don’t really like the feeling that money from ordinary taxpayers is going to people who are knowingly building in floodplain areas,” she says. “That’s not really fair.”

Stephanie arnold spent the night of Fiona mostly sleepless, worried about water seeping into their house. A PhD candidate at UPEI and a staff member at Climatlantic, a federally funded agency providing regional climate adaptation services, their research looks at helping farmers on PEI plan for warming temperatures and changing precipitation patterns.

Arnold is also the current board president of BIPOC USHR (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour United for Strength, Home, Relationship), a not-for-profit support and advocacy organization for BIPOC folks on PEI. Part of BIPOC USHR’s work is to reframe the conversation around climate change. For Arnold, this means acknowledging that climate change has deep roots in colonization and the exploitation of lands and resources. “If we don’t also address those root causes, we’re only putting on Band-Aids,” they say. “And these Band-Aids are only helping specific groups of people.”

Part of their work, both at Climatlantic and BIPOC USHR, involves bringing people from communities whose perspectives have been traditionally marginalized into the climate conversation. That could mean engaging with migrant workers, who increasingly produce much of the Island’s food and many of whom experience inadequate housing, low wages, and poor living conditions. Addressing such injustices might lead to a healthier and more sustainable workforce, helping to improve crop yields at a time when climate change is contributing to food insecurity. But the government and other sectors have been slow to adopt this type of holistic approach. “Sometimes policy makers fall into the trap of making decisions for the communities,” says Arnold, “but not with the communities.”

krystal pike lives on what was once a largely forested rural property but which lost much of that forest cover during the storm. In the days following Fiona, they helped friends and neighbours clear fallen trees from roads with a chainsaw, clean up brush, and haul debris to dump sites. It was only once the adrenalin had subsided that Pyke began to realize the magnitude of their own personal loss. “About two weeks later, when I walked into my forest, I literally fell to the floor crying,” they say. “The trails were gone. The nests were gone. The rabbit paths were gone.”

Coming to terms with destructive events like Fiona can trigger powerful and overwhelming emotions, in part because of the powerlessness we often feel in the face of climate catastrophe. In the months following the storm, Pyke, the ClimateSense project manager at UPEI’s School of Climate Change and Adaptation, organized two community events for Islanders to talk about their experiences of Fiona, including sharing stories of grief. A common theme that emerged was a feeling of disorientation, or what’s known as “sola-stalgia.” It’s a term gaining traction in climate change circles that loosely translates to the loss of a place that once brought you solace. For Pyke, it was important to name what had been lost. “There was a lot of talk about the struggle of moving forward knowing those places don’t exist.”

Almost everyone I spoke to about Fiona has their own story of loss, from viewscapes and trails to the feeling of security and safety. Like many Islanders, my partner and I miss the towering dunes lost at Brackley Beach. Jim Randall still keeps the key to his cottage front door on his keychain, even though there is no door left to unlock. Debbie Langston mourns the dead trees that litter her property and is still jolted afresh by the wide open skyline.

Iconic Teacup Rock—a fixture along North Shore and a draw for locals and visitors—collapsed during the storm. Hope Parnham has fond memories of taking photos there with her children each summer but says it’s vital to remember that the Island is a naturally eroding land mass. Before Teacup Rock, there was Elephant Rock—another popular sea stack structure, in the western part of the Island, lost to erosion and an earlier storm. “It’s like watching the cycle of life.”

But even in the face of larger natural processes, human decisions play a role in the destruction. Parnham is optimistic that Islanders can adapt—if the government leads the way. “People are going to rebuild this year,” she says, “and they need to know how.”