Joyce Ares had just turned 74 and was feeling fine when she agreed to give a blood sample for research. She was surprised when the screening test came back positive for signs of cancer.

After a repeat blood test, a PET scan and a needle biopsy, Ares was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma.

“I cried,” the retired real estate broker said. “Just a couple of tears and thought, ‘OK, now what do we do? ’”

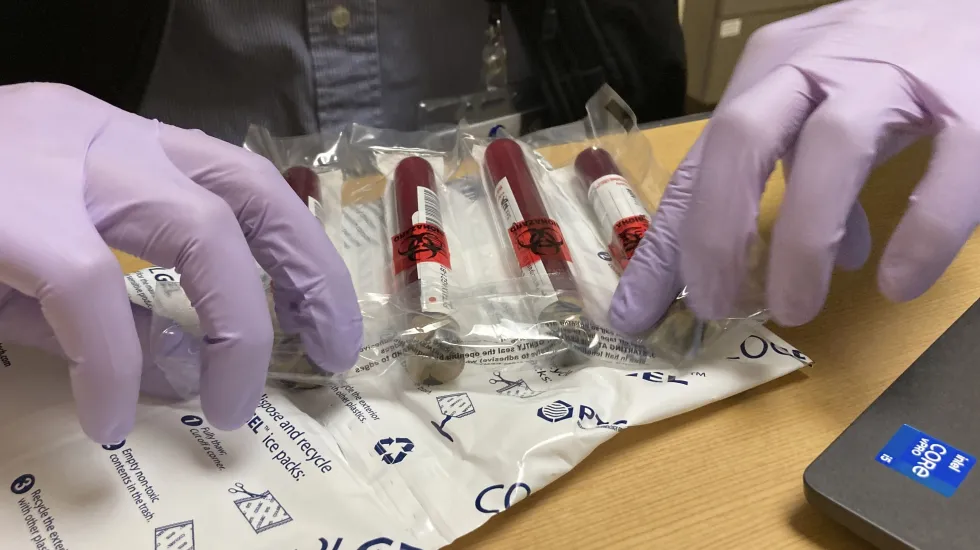

The Canby, Oregon, resident had volunteered to take a blood test that’s billed as a new frontier in cancer screening for healthy people. It looks for cancer by checking for DNA fragments shed by tumor cells.

Such blood tests, called liquid biopsies, already are used in patients with cancer to tailor their treatment and check to see if tumors come back.

Now, one company is promoting its blood test to people with no signs of cancer as a way to detect tumors in the pancreas, ovaries and other sites that have no recommended screening method.

Doctors don’t know yet whether such cancer blood tests — if added to routine care — could improve Americans’ health or help meet the White House’s goal of cutting the cancer death rate in half over the next 25 years.

With advances in DNA sequencing and data science making the blood tests possible, a California company called Grail and others are racing to commercialize them.

And U.S. government researchers are planning a large experiment — possibly lasting seven years and with 200,000 participants — to try to see whether the blood tests can live up to the promise of catching more cancers earlier and saving lives.

“They sound wonderful, but we don’t have enough information,” said Dr. Lori Minasian of the National Cancer Institute, who is involved in planning the research. “We don’t have definitive data that shows that they will reduce the risk of dying from cancer.”

Grail is far ahead of other companies, with 2,000 doctors so far willing to prescribe the $949 test, which most insurance plans don’t cover.

The tests are being marketed without endorsements from medical groups or a recommendation from U.S. health authorities. A review by the federal Food and Drug Administration isn’t required for this type of test.

“For a drug, the FDA demands that there is a substantial high likelihood that the benefits not only are proven, but they outweigh the harms,” said Dr. Barry Kramer of the Lisa Schwartz Foundation for Truth in Medicine. “That’s not the case for devices like blood tests.”

Grail plans to seek approval from the FDA but is marketing its test as it submits data to the agency.

The history of cancer screening offers plenty of reason for caution. In 2004, Japan halted mass screening of infants for a childhood cancer after studies found it didn’t save lives. Last year, a 16-year study in 200,000 women in the United Kingdom found regular screening for ovarian cancer didn’t make any difference in deaths.

Cases like these have uncovered some surprises: Screening finds some cancers that don’t need to be cured.

The flip side? Many dangerous cancers grow so fast that they elude screening and prove deadly anyway.

And screening can do more harm than good. Anxiety from false positives. Unnecessary costs.

And serious side effects can result from cancer care: PSA tests for men can lead to treatment complications such as incontinence or impotence even when some slow-growing prostate cancers never would have caused trouble.

The evidence is strongest for screening tests for cancers of the breast, cervix and colon. Also, for some smokers, lung cancer screening is recommended.

The recommended tests — mammography, PAP tests, colonoscopy — look for one cancer at a time.

The new blood tests look for many cancers at once. That would provide an obvious advantage, according to Dr. Joshua Ofman, a Grail executive.

“We screen for four or five cancers in this country, but cancer deaths are coming from cancers that we’re not looking for at all,” Ofman said.

Dr. Tomasz Beer of Oregon Health & Science University in Portland led the company-sponsored study that Joyce Ares joined in 2020. After a miserable winter of chemotherapy and radiation, doctors told Ares the treatment was a success.

Her case isn’t an outlier, “but it is the sort of hoped-for ideal outcome, and not everyone is going to have that,” Beer said.

While there were other early cancers detected among study participants, some had less clear-cut results. For some, blood tests led to scans that never located a cancer, which could mean the result was a false positive — or that there’s a mystery cancer that will show up later. For others, blood tests detected cancer that turned out to be advanced and aggressive, according to Beer, who said one older participant with a bad case declined treatment.

Grail is sponsoring a trial with Britain’s National Health Service involving 140,000 people to try to determine whether the blood test can reduce the number of cancers caught in late stages.

Ares feels lucky. But it’s impossible to know whether her test added healthy years to her life or made no real difference, said Kramer, former director of the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Prevention.

“I sincerely hope that Joyce benefited from having this test,” Kramer said when told of her experience. “But, unfortunately, we can’t know, at the individual Joyce level, whether that’s the case.”

Cancer treatments can have long-term side effects, he said, “and we don’t know how fast the tumor would have grown.”

Treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma is so effective that delaying therapy until Ares felt symptoms might have achieved the same happy outcome.

Health experts say that, for now, the Grail blood test is not a cancer diagnosis in itself. A positive result triggers further scans and biopsies.

“This is a path in diagnostic testing that has never been tried before,” Kramer said. “Our ultimate destination is a test that has a clear net benefit. If we don’t do it carefully, we’ll go way off the path.”