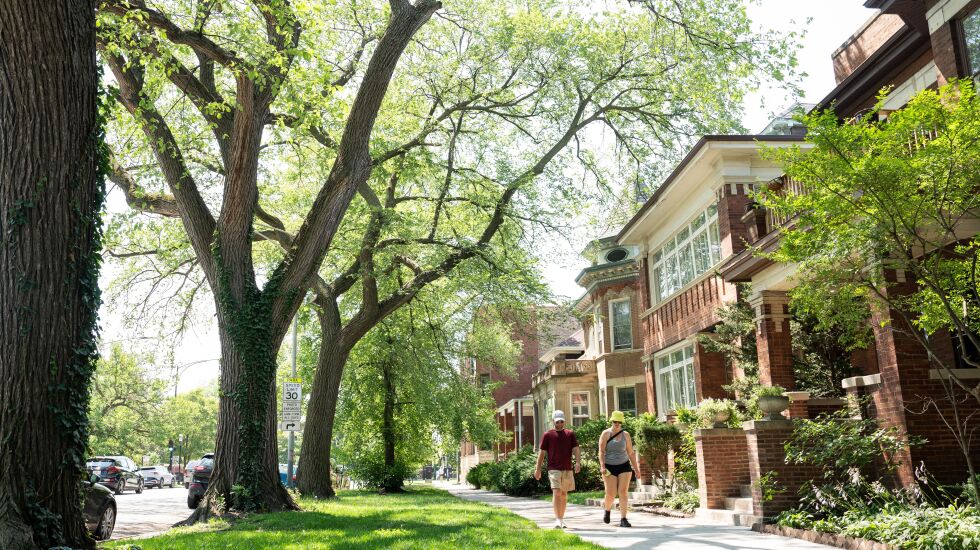

Four stories tall and 5 feet in diameter, the American elms shading West Palmer Boulevard in Logan Square are among the few in Chicago that survived a blight that denuded other city streets some 50 years ago.

Dutch elm disease claimed millions of trees from the 1960s to early 1980s, but the five survivors arching over the sidewalks across the street from Palmer Square Park avoided the fatal fungus, or the chainsaw crews that rushed to take down trees before they got sick and fell on their own.

In the early 1980s, as rows of towering elms, healthy and unhealthy alike, toppled throughout the Northwest Side, West Palmer Boulevard residents rallied to save theirs.

“I saw some kind of tag on them, that they were coming down, and I called the Morton Arboretum,” recalls Steve Hier, who has lived on the 3200 block of West Palmer Boulevard alongside four of the park’s five remaining elms since the 1970s.

After the arboretum, Hier called then-Ald. Dick Mell on behalf of his neighbors and the elms.

“We just said, ‘Don’t take ’em down. Give us a chance to save ’em. If it doesn’t work, so be it,’” Hier recalled. “And I may have said something about chaining myself to a tree.”

In the decades since, homeowners have shelled out thousands of dollars to pay to treat the trees with fungicides, and they have kept a watchful eye for the telltale spray-paint markings that indicate a utility company is looking to tear up the parkway — and with it, the roots of the trees, dating to the 19th century. Hier wants to make sure the trees stay protected as a new generation of homeowners moves onto the block.

Hier wants the City Council to pass an ordinance that would provide for the city to pick up the tab for treating historic elms on public property, encourage trimming and watering, and a mechanism to raise flags across any and all city departments when someone pulls a permit to dig up the soil near the roots of designated trees.

If a city ordinance can designate all buildings facing the boulevards off-limits to tear-down artists, Hier says, a new ordinance protecting trees might allow the elms to live out their 300-year or so lifespans in relative peace.

“I worry about the city putting in new water lines. I worry about some new guy saying he doesn’t like shade, and that’s it,” Hier said in a recent interview under the boughs of the elm spreading over the parkway in front of his house. “We do a lot for buildings and parks, but we don’t really do anything for trees, and they are just as hard to replace.”

Hier was part of a group of residents and preservationists that 20 years ago managed to get the stately mansions and grassy boulevards of Logan Square designated historic landmarks. Hier thinks the elms planted along the boulevards in the 1860s deserve historic preservation, too.

The trees opposite the north edge of Palmer Square Park likely were planted when the boulevards were first laid out in the 1860s. American elms, known for their majestic, arching boughs, were wildly popular across the U.S. and Europe. Then a fungus, native to Asia and carried by beetles, arrived and largely wiped out native species of elms.

Logan and North Kedzie boulevards once were lined like a virtual archway of elm boughs, until the trees were taken down almost overnight.

“The city had contractors that were getting paid by the pound to take down those trees, and they’d come through one day and they’d be gone,” said Stephen “Andy” Schneider, president of Logan Square Preservation, a community organization that helped with the drive for historic status for the boulevards.

Options for saving the trees were limited in the 1970s, and treatments that would protect elms from the Dutch elm fungus cost hundreds of dollars. Chicago and cities across the nation sawed down their elms en masse before they withered and toppled into the streets on their own. Homeowners likewise took down trees on private property rather than risk a dead elm falling on their house — or someone else’s.

But also in the 1970s, the Morton Arboretum was beefing up its staff to do more research. Staff dendrologist George Ware was one of the leading lights in the field of breeding new hybrid elms that could withstand Dutch elm disease.

After Mell called off the chainsaws at Ware’s suggestion, Hier and his neighbors festooned their trees with flypaper-like traps to catch the beetles known to spread the Dutch elm disease. Then they chipped in several hundred bucks each for fungicides. Only one tree, likely infected before it could be treated, didn’t make it. Hier and his neighbors still share the $600-per-tree cost of fungicide treatments every three years.

“It’s well worth it,” said Michelle Warner, who’s paid to treat the tree in front of her house at least five or six times during the 21 years she’s lived across from the park. Warner notes trees disappearing across the city because of the emerald ash borer, which in recent decades has been tearing through North America’s ash trees the way Dutch elm wiped out elms decades ago.

“I can see why the city wouldn’t want to treat all the trees. There are so many of them; maybe you have to take them down,” Warner said on a recent morning, as she watched a tree service boring small holes in the elms’ roots to begin pumping in around 50 gallons of fungicide. “But it would be nice to see the city be a little more proactive about protecting some of the ones that have been here for 100 years.”

This spring, Warner and Hier fended off a crew preparing to dig up the parkway to install cable lines, persuading them to dig up the sidewalks opposite the parkway.

First Ward Ald. Daniel La Spata said he had yet to dive into Heir’s proposal for the city to treat the elms and flag any permits to dig near designated trees.

“I would say that I broadly support protecting our urban forest, including in these particularly historic trees,” La Spata wrote in a text to the Chicago Sun-Times. “We’re in a very preliminary place of understanding what a historic designation or protection would look like and at what level of government.”

In the meantime, Hier and his neighbors are on guard. Based on his experience on the campaign to win historic designation for the boulevards, Hier estimates there are another two years before a tree-focused ordinance lands in front of the City Council.

“Well, if they leave them alone, these trees will live 300, 400 years,” Hier said. “So we’ve got time.”