When Raul bought his home in 1999, he had no way of knowing that just two years later, Tropical Storm Allison, as it inundated Houston with more than 30 inches of rain, would submerge his street in a northeastern neighborhood called Lakewood. He rebuilt after Allison—and after major floods in 2008, and again in 2015, and most recently two years ago after Hurricane Harvey. When I ask Raul, who declined to share his last name, how much longer he thinks he’ll stay here, he points to the ground. He’ll leave when he’s returned to the earth itself.

Raul’s story is common in Lakewood, where a strong rainstorm can push water up to front porches. The neighborhood sits alongside Halls Bayou, a tributary of the larger Greens Bayou watershed, and its main drainage system is a series of open, concrete ditches between the curb and the road, where you might otherwise expect to see a sidewalk. The ditches, built decades ago and which in some places seem like hardly more than a gentle dip in the road, are designed to funnel water toward a culvert at the end of each block. The system isn’t structured to handle downpours like those sustained during Hurricane Harvey, but it should be able to shuttle water out of the neighborhood during regularly occurring storms. Yet the drainage infrastructure is so poorly maintained, it’s effectively useless. The grass has grown over the ditches, almost leveling them out in some places. Lawn signs, leaves, mud, and trash clog the entrances to the storm drain. Even when the ditches are funneling water away, it can take hours for them to empty completely. Residents often end up clearing out the ditches on their own.

“These communities outside the [city center] are stuck with this really primitive open ditch drainage that would normally be reserved for rural areas or small towns,” said Charlie Duncan, a director at Texas Housers, a nonprofit that advocates for low-income housing services.

When Lakewood was built in the 1950s, it was a rural area. Decades ago, when the neighborhood was still mostly middle-class and white, its open ditch drainage system was sufficient because the land upstream from the bayou was still undeveloped and could thus absorb runoff.

There’s been significant development in the area since then, but the neighborhood’s flood protections haven’t changed much. That’s true across large swaths of Harris County, where drainage infrastructure is an uneven patchwork. Some parts of the county have measures intended to protect residents against a 100-year storm, while others, like Lakewood, have far fewer protections, and experience small-scale, localized flooding on a regular basis. “The system wasn’t built all at once,” said Kyle Shelton, a director and researcher at Rice University’s Kinder Institute. “There was never a huge collection of money to say, ‘OK, we’re building all these [protections] to the same level.’ All of those infrastructure projects are usually piecemeal.”

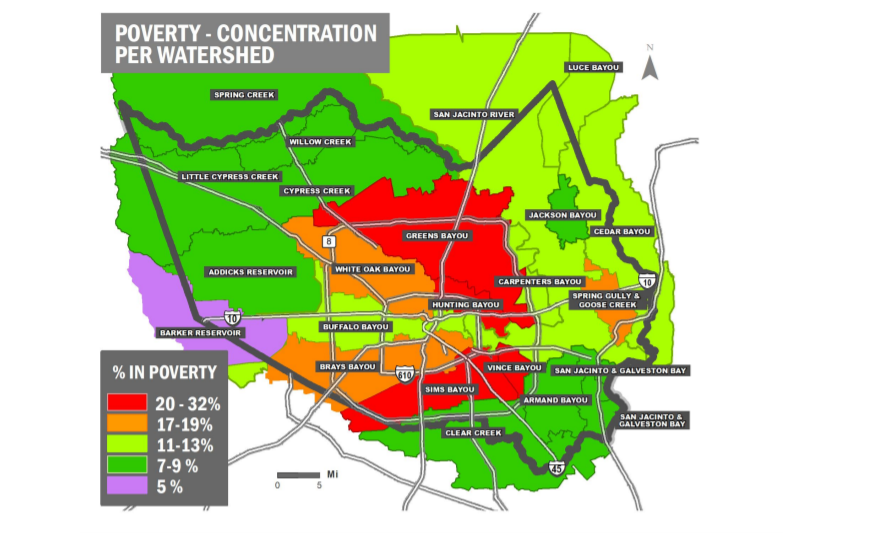

And then there’s the question of who gets funding for new projects. Greens Bayou has one of the highest concentrations of poverty in the county. Lakewood is predominantly black and Latinx, and the median home value is $56,200—nearly a quarter of the citywide median. In Halls Bayou, most of the 37 tributaries haven’t even been studied by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Homes along those tributaries may not be included in the floodplain maps, which means the risk of flooding isn’t officially quantified.

Federal projects are usually funded after complicated cost-benefit analyses which rely in part on property values. But that means low-income neighborhoods like Lakewood have long been passed over for resources that instead flow to wealthier Texans.

“Right away, that discriminates,” said Iris Gonzalez, the director of a Houston-based advocacy group called the Coalition for Environment, Equity, and Resilience (CEER). “It means that poor communities and communities of color just can’t score enough to get federal projects.”

But for communities like Lakewood, help could be on the way. Last year, on the first anniversary of Hurricane Harvey, 85 percent of Harris County voters approved a historic $2.5 billion flood infrastructure bond deal. The bond language states that “flooding issues do not respect jurisdictional or political boundaries,” giving the County Commissioner’s Court authority to “provide a process for the equitable expenditure of funds”—but what that equitable process looks like isn’t specified.

As Harvey’s second anniversary nears, community advocates worry that absent a tangible plan and process, the bond money—most of which hasn’t been disbursed—will likely benefit affluent communities first, before the studies are even complete on the types of detention ponds or channel improvements that Halls Bayou needs.

“The idea that some areas have been overlooked in the past—there is some truth to that in parts of Harris County,” said Matt Zeve, the deputy executive director of the Harris County Flood Control District, which will manage most of the infrastructure projects funded by the bond. “We can’t make up for lost time, but what we can do is recognize that the work hasn’t been done in the past, and we need to dedicate the financial resources to that work.”

–

“This neighborhood is affordable,” says Ben Hirsch, who works at West Street Recovery, a nonprofit that rebuilds homes in neighborhoods like Lakewood. For the most part, residents here wouldn’t be able to buy a detached, two-bedroom house with a yard in any other part of the city. “But it’s only affordable because of the risks.”

More than $100 million from the bond has been earmarked for Halls Bayou, but in the decade that it might take to disburse the promised infrastructure funding and complete the county’s master list of planned projects, Hirsch believes the area will continue to flood, in small storms or historic ones. “The most progressive organizations in the city will say, ‘Well, you know this money is coming’—because there is nothing else to say,” he said.

But even $100 million isn’t going to save these neighborhoods. It’s “only a sliver of what we need for resilience,” said CEER’s Gonzales. Many of the projects listed to receive funding “were already on the top of the list,” she said. Chrishelle Palay, the executive director of the Houston Organizing Movement for Equity (HOME), also points out that the bond’s equity provisions don’t establish a clear, transparent process. “There isn’t a policy in place to make sure that a resident in any watershed would know how the order [of projects] that are underway is determined,” she said.

The fact that the equity commitment is so vague has also led others to accuse the county of attempting to siphon funds away from wealthy communities that were also hit hard by Harvey. Houston City Council member Greg Travis advised the County Commissioner’s office against “conducting social engineering to decide which projects should be funded immediately.”

In February, state Representative Jim Murphy told County Commissioner Lina Hidalgo that prioritizing bond projects based on neighborhood income levels was “outside of the scope” of the bond program, and could therefore threaten the Legislature’s effort to provide disaster funding to Harris County. Hidalgo later clarified to the Houston Chronicle that income data was not being used to determine project timelines.

Of the 17 bond projects dedicated to Halls Bayou, seven are in the preliminary design phase; the rest have yet to make it to that first step. For most infrastructure projects managed by the Flood Control District, the design phase could take up to a full year, Zeve tells me. The timeline for the next stage—acquiring right of ways from private citizens and businesses, and environmental permitting—is messy and unpredictable. It could take a few months, a year, or longer, Zeve said. After that, the project moves on to the final design phase for another nine to 12 months. Then, and only then, does construction begin—which can last anywhere from one to four years depending on the size of the project. Throughout the yearslong process, Zeve said, “There’s a lot of work being done, but anyone who’s not in the contracting or engineering community doesn’t see anything happening.”

–

Shirley Ronquillo, a community activist from East Aldine, knows a few things about agitating for action. In her neighborhood on the far northeast side of the city, homeowners on opposite sides of the street are divided by city and county jurisdiction lines. For years, Ronquilo has been unable to get requests regarding even mundane issues like potholes addressed. Is it the city of Houston’s pothole, or the county’s? No one seems to know, or, she suspects, care. She points to the fact that when the county was conducting outreach ahead of last year’s bond vote, none of the community programs were held in Spanish in this primarily Latinx, working-class community.

“How much do you need to study the flooding? We know it floods,” she said. Earlier in our conversation, Ronquillo told me that when she was growing up, she and her family would swim across major roads toward safety whenever the flooding got too bad. East Aldine has the same poorly maintained open-ditch drainage system as in Lakewood.

What the county doesn’t know, Ronquillo said, is that residents in this corner of the city are often reluctant to apply for funds to rebuild and repair homes that were destroyed by floods because they don’t have the right paperwork: sometimes related to immigration status, sometimes related to property deeds or permits. Two years after Hurricane Harvey, children are still living in homes that show signs of water damage and mold.

As we drive through East Aldine, Ronquillo points to each block, listing off how high the water reached during Harvey as well as the last time it flooded from an unusually strong burst of rain. Streets that fall out of the city’s jurisdiction, and its commercial zoning laws, are lined by taco trucks, auto-repair shops, and mobile home parks. Men on horses ride past cars on the narrow two-lane road.

The unchecked growth that happens in unincorporated areas makes it harder to measure and mitigate flood risk. Every new patch of concrete means more runoff.

The City of Houston is unlikely to annex this portion of Harris County soon. (After the city’s expansion spree slowed in the 1990s, the state made it harder for cities to acquire new land.) But if the city were, someday, to annex the patchwork of streets that are part of unincorporated Harris County, the infrastructure issues here would be added to what Duncan, Texas Housers’ advocacy director, calls Houston’s “infrastructure debt”—one more network of poorly maintained ditches to upgrade and maintain. “It’s going to require a more concerted effort to improve that infrastructure that’s so far behind,” he said.

East Aldine won’t face the same fate as Lakewood, which became part of a forward-facing city with an economy larger than the state of Maryland, but is now stuck with the services of a small, unincorporated community from the past.

With $2.5 billion on the table, Harris County is poised to fix some of its longstanding issues. But only time will tell how much longer some communities have to wait.

READ MORE:

-

Sunk Costs: Back-to-back record flooding along the Brazos River forced people in Richmond to make an excruciating choice: Stay or go?

-

Sinking Land and Climate Change Are Worsening Tidal Floods on the Texas Coast: More than 10,000 homes along the Texas coast will flood at least 26 times a year by 2045, researchers say.

-

Floods Drown ‘High Ground’ in Uncertain, Texas: Time has always been a friend to those who live on the west side of Caddo Lake, but in March of 2016, time became their enemy.