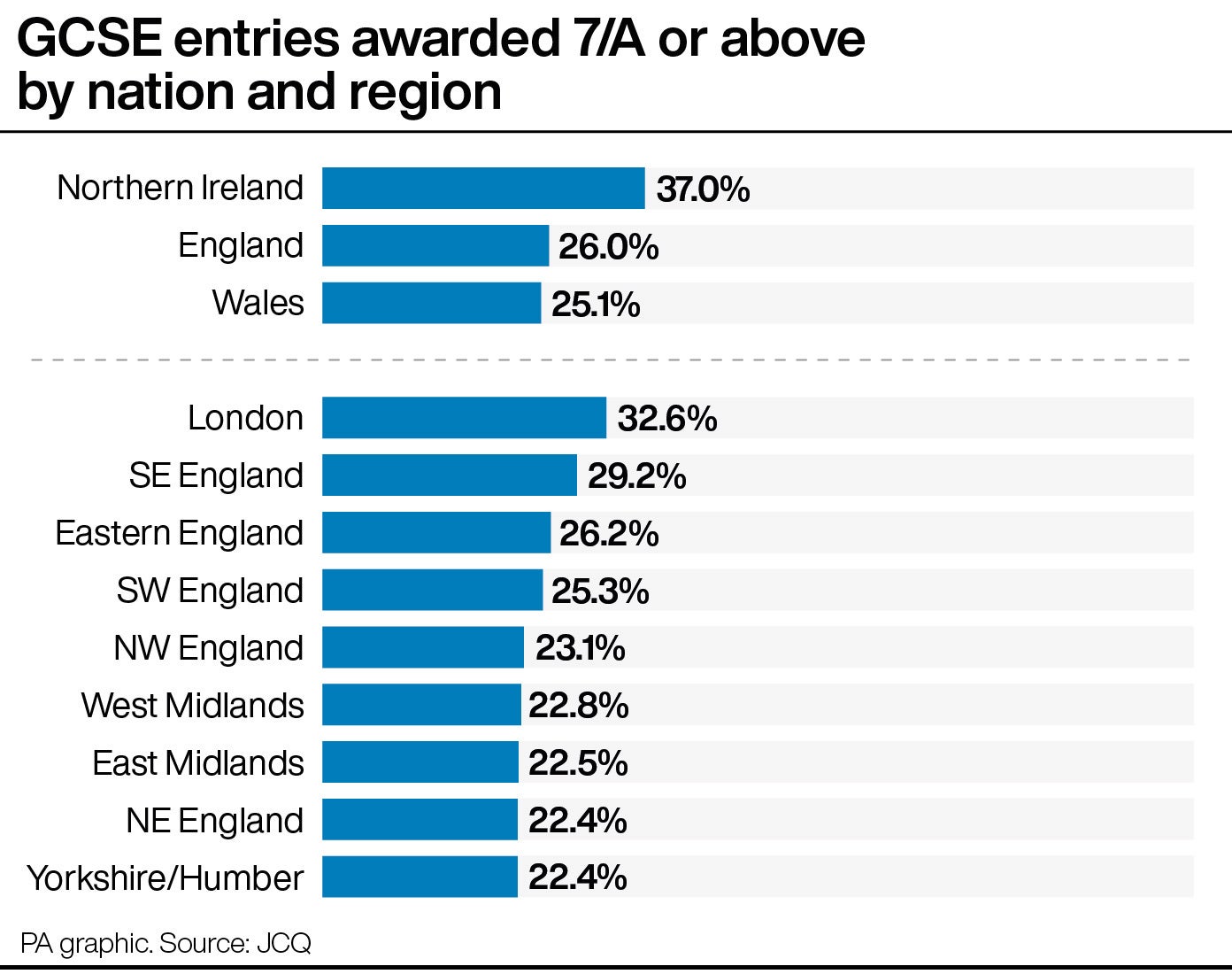

Schools are in urgent need of a recovery plan after the attainment gap in top GCSE grades between the north and south of England widened, an educational charity has said.

Every region across the country saw a fall in the proportion of pupils getting a 7/A or above, but the divide between the highest and lowest-achieving areas since before the pandemic grew.

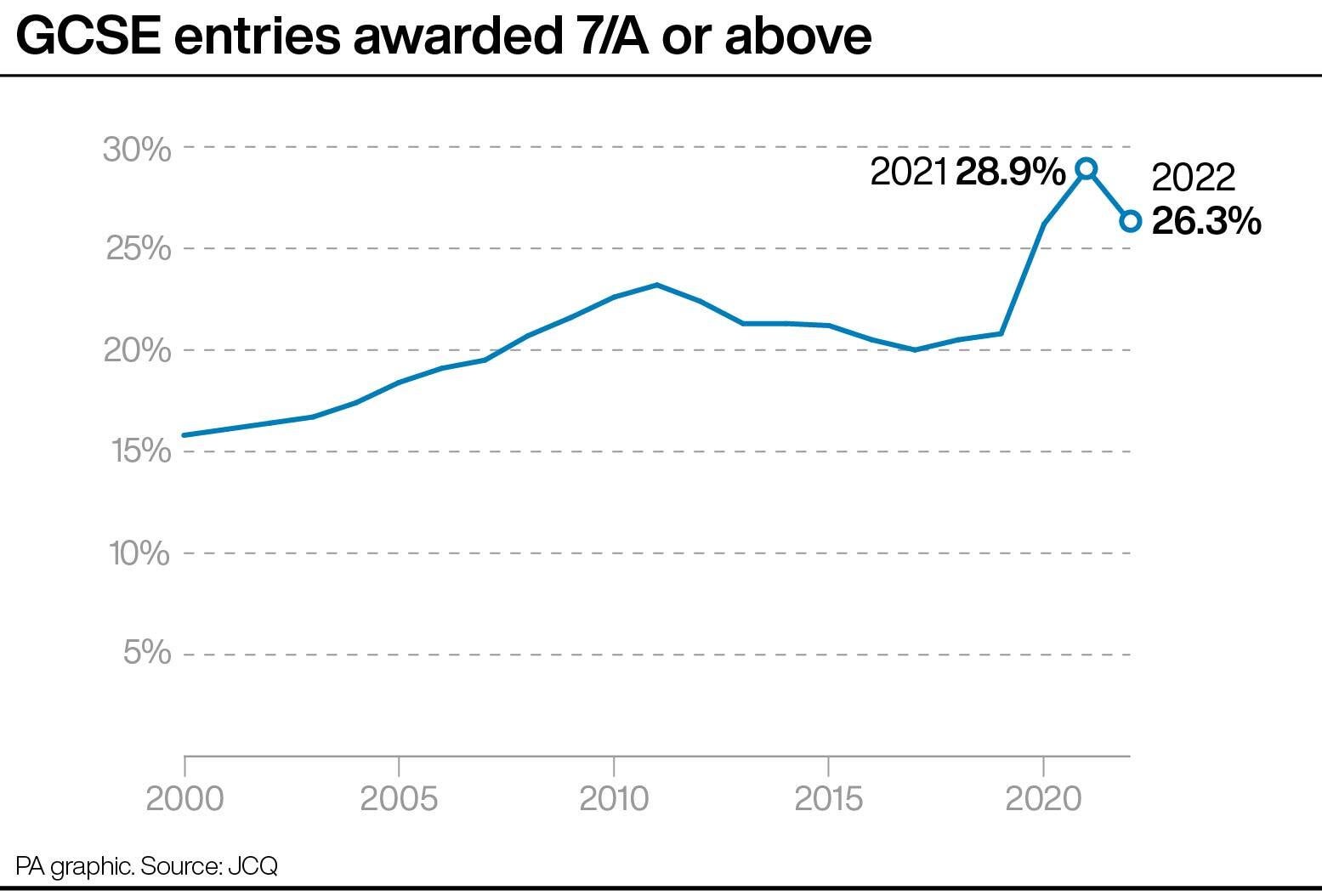

As expected, with the return to formal exams for the first time in three years, top grades fell from 2021 levels but remained higher than in 2019.

Figures published by the Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) – covering GCSE entries from students predominantly in England, Wales and Northern Ireland – showed top grades of 7/A have fallen from 28.9% in 2021 to 26.3% this year, a drop of 2.6 percentage points.

But this remains higher than the equivalent figure for 2019 of 20.8%.

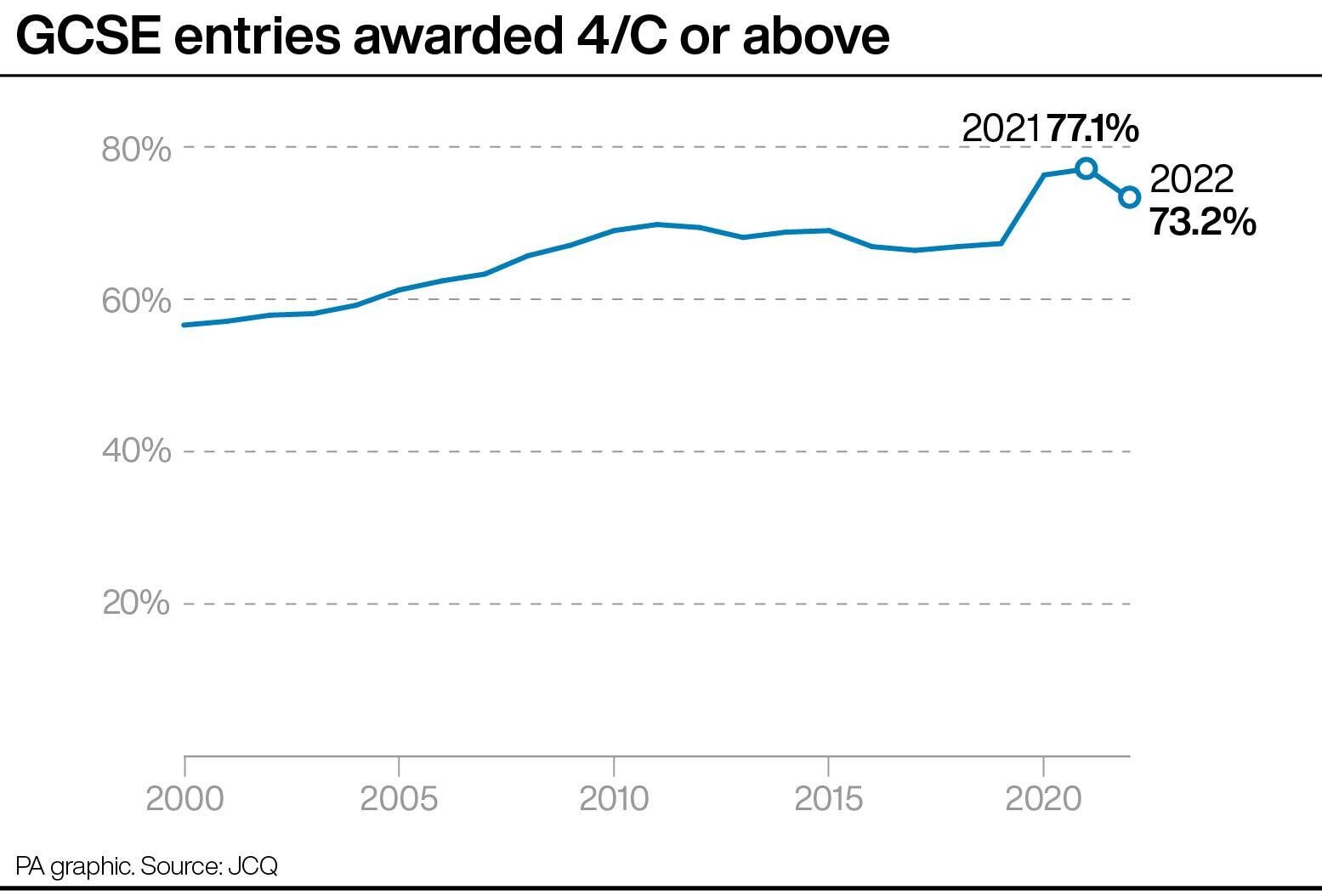

The proportion of entries receiving a 4/C – considered a pass – dropped from 77.1% in 2021 to 73.2% this year, a fall of 3.9 percentage points, but higher than 67.3% in 2019.

The overall rate for grades 1/G or above this year was 98.4%, down from 99.0% in 2021 but slightly above 98.3% in 2019.

Schools minister Will Quince has insisted closing the attainment gap is a “huge priority” for the Government, as Labour accused the Tories of having “failed” children amid regional disparities in results.

Both the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber were at the bottom of the table when it came to top grades this year, some 10.2 percentage points below London.

While 22.4% of students achieved a 7/A or above in the two northern regions, the figure was 32.6% for London.

This is almost unchanged from last year, which saw a gap between London and the North East of 10.0 percentage points.

But the divide has widened from 9.3 percentage points in 2019, when 16.4% of students in the North East got a top grade, compared with 25.7% in London.

Schools North East, which describes itself as dedicated to improving outcomes for young people in the north-east of England, said the increased gap shows that adaptations made this year such as more generous grading and focused revision topics had not gone far enough.

The organisation said: “It is clear that the disproportionate impact of the pandemic in regions like the North East has not been effectively taken into account.

“This year’s results can be seen as a ‘map’ of the impact of the pandemic on students and schools.”

The group’s director, Chris Zarraga, said the pandemic had exacerbated “serious perennial issues, especially that of long-term deprivation”, as he called for a support plan.

He said: “Schools urgently need a properly thought-through and resourced ‘recovery’ plan, that recognises the regional contexts schools operate in, with a long-term view of education and a curriculum that is appropriate and accessible to all students and schools.”

Mr Quince told Times Radio: “Ensuring that wherever you live up and down our country that you have access to a world-class education, and you have the same opportunity – whether you live in Bournemouth or Barnsley – is really important to us, and every year up until the pandemic we’ve been closing the attainment gap.”

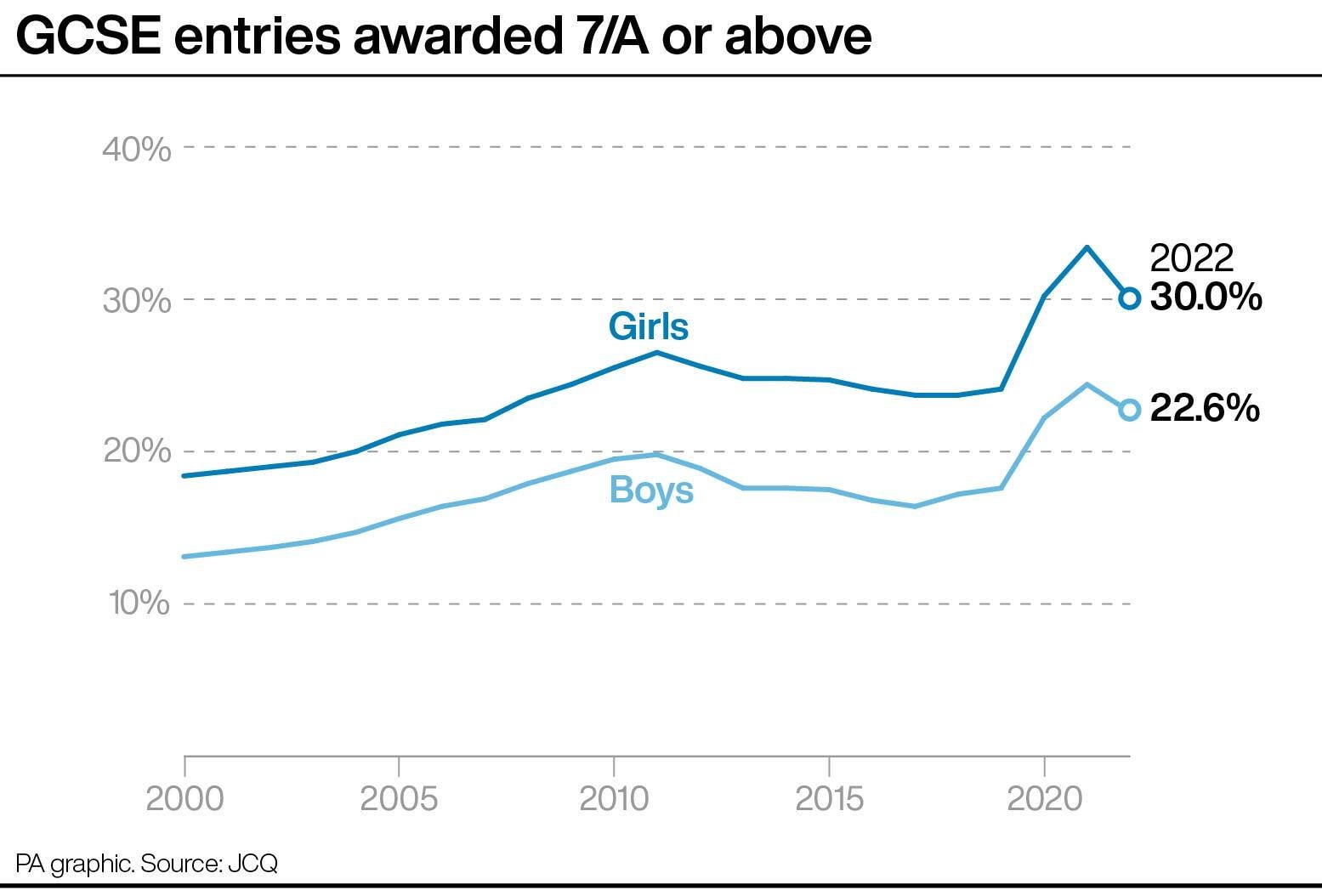

Girls continued their lead over boys this year, with 30.0% of entries achieving a 7/A, compared with 22.6% for males.

The gap has closed slightly from last year, when 33.4% of female entries were awarded 7/A or above compared with 24.4% for males, a lead of 9.0 percentage points.

Business studies saw the biggest percentage rise in entries of any major subject, while computing overtook PE for the first time since the subject was introduced in 2014.

Separate figures, published by exams regulator Ofqual, showed that 2,193 16-year-olds in England got grade 9 in all their subjects – including 13 students who did at least 12 GCSEs.

While traditional A*-G grades are used in Northern Ireland and Wales, in England these have been replaced in with a 9-1 system, where nine is the highest.

A 4 is broadly equivalent to a C grade, and a 7 is broadly equivalent to an A.

Kath Thomas, interim chief executive officer of JCQ, welcomed the return of exams, describing them as “the fairest way to assess students and give everyone the chance to show what they know”.

Dr Jo Saxton, Ofqual’s chief regulator, said the results were “a testament to students’ hard work and resilience” and that she had met students and staff who wanted exams and formal assessments to take place, with pupils keen for “a chance to prove themselves”.

The Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL) said there has been a “strong indication” from its members that they want mitigations put in place again in 2023 “because next year’s cohort will have also been heavily impacted by Covid”.

An Ofqual spokesperson reiterated its position that it wants to “get back to pre-pandemic standards” but added that it will “reflect on the results this year” and make an announcement on 2023 arrangements in the autumn.

A spokeswoman for the Department for Education said it is their intention “to return to the carefully designed and well-established pre-pandemic assessment arrangements as quickly as possible, given they are the best and fairest way of assessing what students know and can do”.

Meanwhile, exam board Pearson apologised to students after thousands were deemed ineligible to be awarded BTec grades on Thursday, a week after other pupils faced delays in getting results from the same awarding body.