Behind a fortress wall and razor wire and a few feet away from California's death row, students at one of the country's most unique colleges discuss the 9/11 attacks and issues of morality, identity and nationalism.

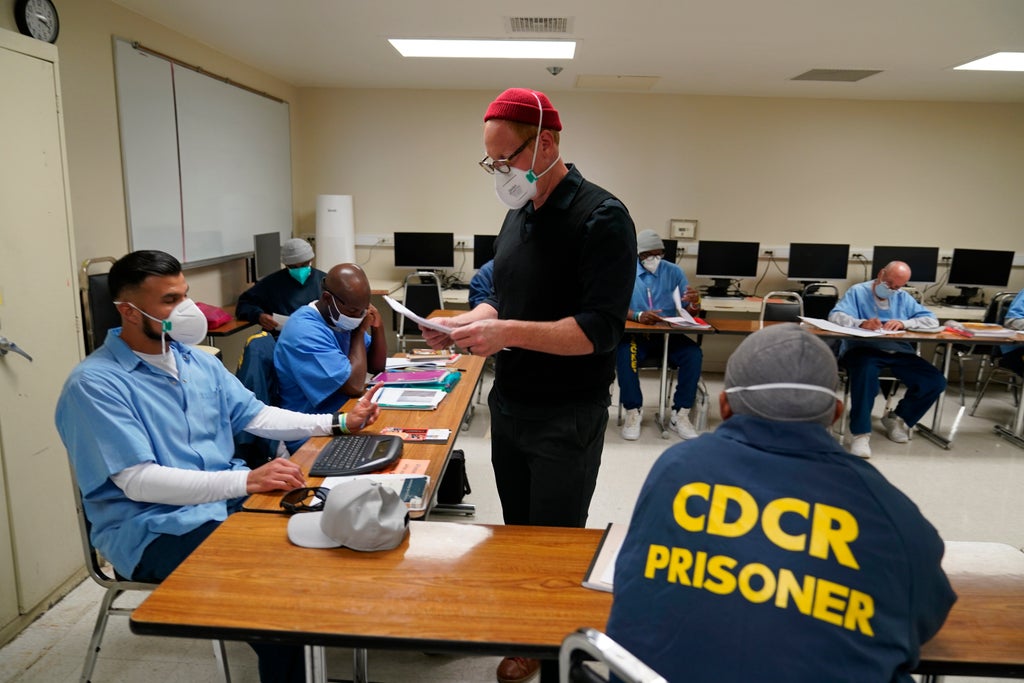

Dressed in matching blue uniforms, the students only break from their discussion when a guard enters the classroom, calling out each man's last name and waiting for them to reply with the last two digits of their inmate number.

They are students at Mount Tamalpais College at San Quentin State Prison, the first accredited junior college in the country based behind bars. Inmates can take classes in literature, astronomy, American government, precalculus and others to earn an Associate of Arts degree.

Named for a mountain near the prison, the college was accredited in January after a 19-member commission from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges determined the extension program based at San Quentin for more than two decades was providing high-quality education.

“This is a profound step forward in prison education,” said Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, the umbrella organization for all U.S. higher education institutions.

Mitchell said Mount Tamalpais College is “an extraordinary model" that will give it autonomy not seen in prison programs attached to outside schools.

The new designation will force the school to maintain the high standards set by the college association and hopefully catch the attention of donors to help the college expand, said President Jody Lewen. While it can accommodate 300 students per semester, another 200 are on a waiting list.

The college is one of dozens of educational, job training and self-help programs available to the 3,100 inmates in the medium-security portion of San Quentin, making it a desired destination for inmates statewide who lobby to be transferred there.

“I wish I had learned this way coming up; instead I was in special ed my whole life," said 49-year-old Derry Brown, whose English 101 class “Cosmopolitan Fictions," was discussing “The Reluctant Fundamentalist,” a novel by Mohsin Hamid.

Brown, who is serving a 20-year sentence for burglary and assault, earned his GED in prison and takes pride in now being a college student. He said he may pursue a career in music in his hometown of Los Angeles once he's released next year.

“There is joy in learning — that’s why I want to continue," he said. “Even when I get out, I’m going back to college.”

The college's $5 million annual budget is fully funded by private donations, with a paid staff and volunteer faculty, many of them graduate students from top universities, including Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley.

The previous program started in 1996 and was later known as the Prison University Project and it also offered associate’s degrees but Lewen, who started as a volunteer instructor in 1999, said she began the process to have an autonomous college three years ago when the university they partnered with closed.

“Very often in the field of higher ed, people will look at educational programs in prisons and they’ll say, ‘Well, that’s a program or project. It’s not a school.’ Our hope is that by being an independent, accredited, liberal arts college that operates in a prison we make it more difficult for people to overlook those inside and we help them imagine our students differently,” Lewen said.

Any general population San Quentin inmate with a high school diploma or GED certificate is eligible to attend. The prison's 539 death row inmates are excluded.

Guards check the IDs of students coming to classes held in trailers set up on one edge of the prison's exercise yard, where students stop to discuss their assignments — corrections officers watching from four towers above.

Overhearing those yard conversations made a big impression on Richard “Bonaru” Richardson after he was transferred to San Quentin in 2007 to finish serving a 47 years-to-life sentence for a home invasion robbery. Former Gov. Jerry Brown commuted Richardson’s sentence, and he was released last year after serving 23 years.

“In other institutions, we were used to talking about gang activity, violence, knives, drugs, the next riot,” he said.

In San Quentin, the conversations were often about what classes they were taking, how to write a thesis or how to defend an argument.

“I was taken aback. It was kind of like, ‘Hold on, isn’t this supposed to be a prison?’” he added.

He decided to sign up after seeing a group of female volunteers walk across the prison yard.

“I got into the classroom for all the wrong reasons, but I realized that I was actually learning something and that there were people who believed in you more than you believe in yourself. When you see that, you start believing in yourself,” he said.

In his 14 years at San Quentin, Richardson, 47, rose to become executive editor of the inmate-led San Quentin News, a monthly newspaper distributed to California’s 35 prisons that has highlighted the prison programs and often publishes inspirational stories of men who pursued higher education while incarcerated.

He now works as an advancement associate helping the college's communications and fundraising departments.

“Like me, some of them might be the only person in their family to ever have a college degree and that inspires your children to continue their education. For some of them, it’s the greatest achievement of their lives,” Richardson said.

Doug Arwine, a high school humanities teacher, began volunteering this year and teaches English 101, which focuses on developing critical thinking skills.

He said he cherishes helping his students “share experiences and share their humanity with one another."

“There's also moments of success when a student realizes that they’ve crafted a really elegant paragraph in their essay, and they’ve made some interesting points. As with any student, regardless of where you are, you can see how that helps them build confidence,” Arwine said.

Teaching at San Quentin is also a unique experience. The process of going through layers of security, teaching the two-hour class, then clearing security again at the end of the day takes about five hours, Arwine said. He invests many more hours grading papers and preparing for his twice-a-week lessons.

Many of his students dropped out of school at an early age or went to dangerous public schools, Arwine said.

“I really believe in the values that Mount Tamalpais College espouses, in terms of offering free educational opportunities for incarcerated people because as we know from social science research, the best way to reduce recidivism rates is through offering educational programming while they’re incarcerated. It’s arguably the best form of rehabilitation,” said Arwine, whose father spent time in prison.

A 2013 Rand study found that inmates who participate in correctional education programs had 43% lower odds of re-offending than those who did not and were 13% more likely to obtain employment.

Jesse Vasquez, 39, said he was serving multiple life terms for attempted murder, a drive-by shooting and assault with a deadly weapon at a maximum-security facility when he read about the program in the San Quentin News and decided he would transfer there one day.

Vasquez had taken correspondence college programs at other prisons but studying in a classroom at San Quentin helped him see his potential and he realized he was at a “hub of rehabilitation."

The courses challenged him to question what he was learning and helped him build up critical thinking skills, which he called “a pivotal moment."

Vasquez’s sentence was commuted by the governor in 2018 after he had served more than 19 years. He was released in 2019 and now works for Friends of San Quentin News, a nonprofit that supports the newspaper.

He said having the students be enrolled at an actual community college will be an even greater incentive for them to pursue higher education and hopefully encourage other prisons to have their own colleges.

“All of a sudden, more people might be more open to the idea of, ‘Hey, what if we try this revolutionary idea somewhere else?’” he said.