The existence of white privilege, the idea that unseen, unconscious advantages afforded to white people shapes systemic injustice, has been hotly contested since the term was popularized by women’s studies scholar Peggy McIntosh in 1988. Many working class and poor whites have questioned how they could possibly experience privilege while living through things like food insecurity, lack of medical care or stable housing, and low quality schools.

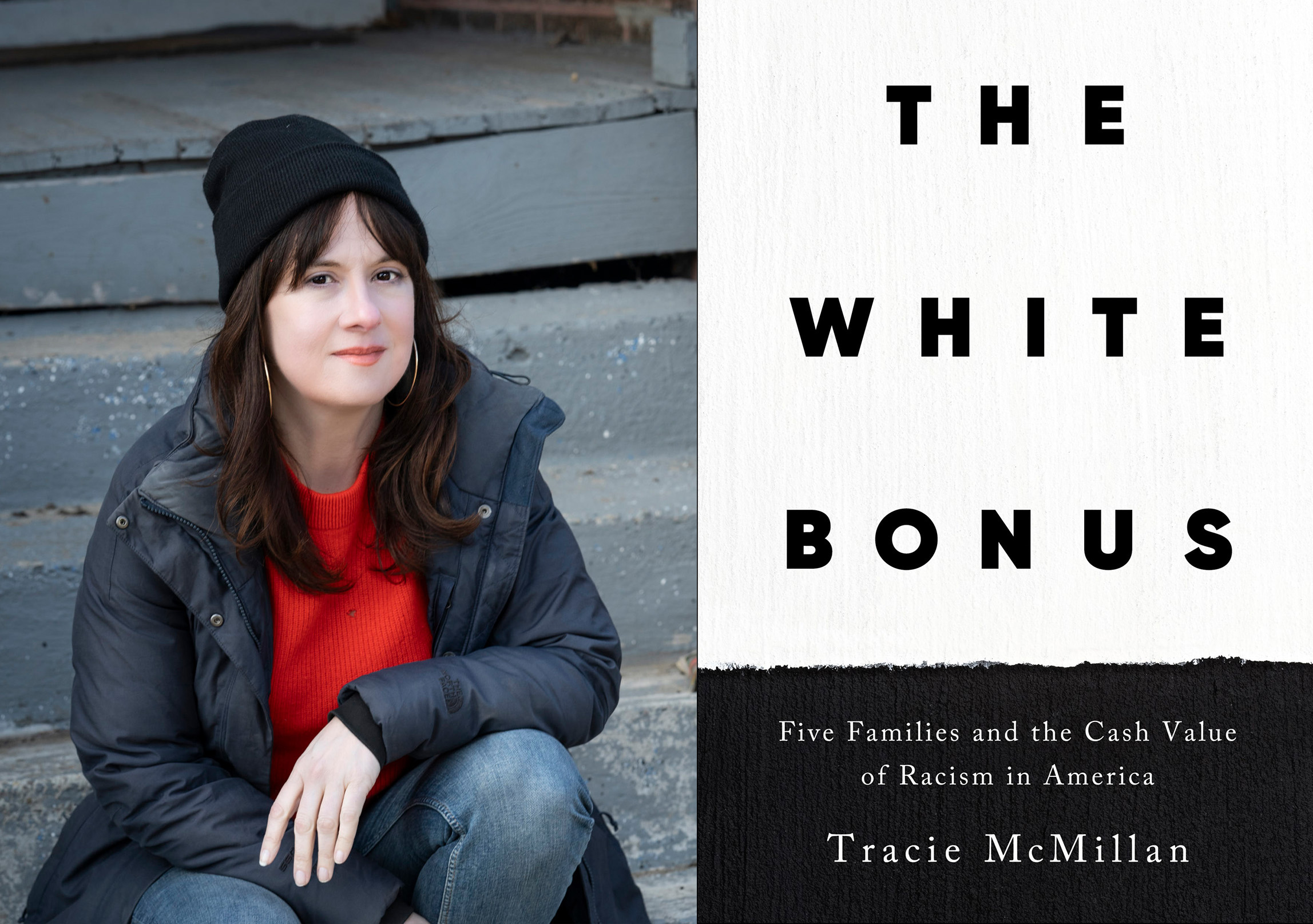

In The White Bonus: Five Families and the Cash Value of Racism, poverty and labor reporter and Capital & Main contributing editor Tracie McMillan seeks to put a dollar amount on the notion of privilege. In her own case, McMillan estimates a white bonus of about $146,000 in financial help from her family. Her family’s ability to build that wealth, she notes, was aided by discrimination in such areas as housing, employment and union membership. She follows three generations of her own family, documenting advantages that allowed them to get good jobs, buy homes and live comfortably. She also expands her investigation to four other white subjects to examine white America’s notions of who deserves to live well, and how one is expected to live when you are not one of the lucky ones.

McMillan spoke to Capital & Main about how racism benefits white people, and whether it is worth it for white people to keep buying into those ideas.

This interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

Capital & Main: What drew you to writing about how systemic racism benefits white people?

Tracie McMillan: I started thinking about the cash value of racism probably around 2016 because I was watching the rise of President Trump as a candidate and reading things like Hillbilly Elegy. As a white person who doesn’t come from a lot of material wealth, I just felt like a lot of the conversation was getting stuck [around] ”What do I get for being white?” I think a lot of times people ask that question in a pugnacious, argumentative way. Like, “Well, what have I ever gotten for being white? You know, I don’t have a good job” or this or that. I think the instinct often is to just deflect that and be like, “Well, we’re not even going to talk about that.” And for me, I was like, “Well, what if we tried to talk about that?”

What is the white bonus?

The white bonus is an estimate of the money white people get because of white supremacy. It’s a variation or a variant of white privilege, but it’s specific and concrete. I don’t think I would have much understanding of the scale, scope and depth of racism in my country if I hadn’t taken that perspective.

When your privilege just gets real relative, for example, I put myself through university. I’ve been so poor I’ve been passing out from hunger. Like, what has whiteness ever gotten me? And I’m like, “Oh, well, a job that got me through college, which turned into the internship that got me into journalism. Which turned into another job. I got an apartment in New York because a very wealthy, well-connected white man signed on to my paper for me.”

“Racism is the language we use to justify the idea that some people are worth more than others.”

Can you talk a little bit about your methodology for calculating the white bonus?

This is like a rough back-of-the-envelope estimate. This is not social science. All of it I would say is like a drastic underestimate.

It’s got two parts. One is the family bonus and one is a social bonus. The family bonus is how much money your family has given you since you left home or turned 18, or spent on you paying for tuition, paying for an apartment, paying for a cell phone, car insurance. A little bit before 18, if they were paying for test prep or other things to help you sort of leverage social mobility. Then you go back through the family history and say, well, how likely is that? Your family would have had that money if they weren’t white?

That means looking at things like employment discrimination for your parents. Was that working to their advantage? And if it was, how important was that for them to be able to have money to spend on you or resources?

The social bonus is more looking at how much more money you were able to earn because you were white. If you got a job because you were white, that pays better than other jobs or you sort of can calculate that out. There’s really good data on sort of racial wage disparities, [loans] that you could access. You’re going to be looking at employment discrimination that works in your favor.

So much of the book is centered around the theme of deserving. Who deserves what? How does that notion of deserving, based on race and class, shape our culture and society?

I think Americans are really obsessed with making sure that folks deserve what they’re getting. Racism is the language we use to justify the idea that some people are worth more than others. The core thing is that, like we use skin color as the reasoning for it. But the point of it is not actually skin color. The point of it is just to justify some people getting stuff when others don’t.

Racism is the language and the vocabulary we use to sort of trick people out of thinking everybody’s equal. You just get people ginned up on proving who deserves something, as opposed to just being like, we all deserve to have enough. We have enough for everybody to be OK. And maybe we should stop fighting constantly over who deserves the tiniest scrap.

This is the concern I have when we focus only on racial equity and only on representation. It’s like, well, which point in the white class structure are you trying to bring folks up to? Because the bottom of the white class structure is still pretty crummy.

“There’s really good psychological research about how whenever a conversation about white racism comes up or white racial advantage comes up, almost all white people immediately deflect away from racial advantage to talk about class.”

There is a scene in the book where you are struggling to help your mother go to the bathroom, where you learn a really difficult lesson that is repeated when your father beats you when you leave for college. In both these instances, people are looking on and watching but are doing nothing to help you. And the lesson that you take from it that you write is if nobody was looking out, it’s silly for me to look out for everyone else.

I think this is a really deep part of white culture, honestly. Or at least that’s how I’ve observed it. I would say at least in the community I grew up in, particularly with women, the idea was if you are getting hurt by the system that’s around you, you just gotta grin and bear it and endure and persist and be resilient and push on through and figure it out.

I think that is something that’s repeated across generations, across entire communities. The idea that you would come from that community, you go out into the world, and then you hear people talking about racial equity or racial justice — it’s a really hard pill to swallow. You’re just like, “Why am I supposed to stand up for somebody else? But nobody would stand up for me.” That’s a really deep problem in our society.

I think with where both our politics and our policies are right now, you see how dangerous that makes the world for people.

You mentioned the instinct is to deflect and not talk about it. Is that a protection mechanism for white people?

There’s really good psychological research about how whenever a conversation about white racism comes up or white racial advantage comes up, almost all white people immediately deflect away from racial advantage to talk about class.

I think for me, it was really striking to realize how much recent history in the place that I grew up had been sort of buried or hidden from me.

The school district my parents had bought a home in initially, right, had been sued in 1968. It was the first northern school district to be sued by the feds for operating a segregated school district. And that [Michigan] district, Ferndale [Public] Schools, fought tooth and nail to preserve segregation for 13 years. Journalists at the time documented that the district went without about $2 million in public funding from the feds because they refused to integrate one of their elementary schools. So they integrated in January 1981. And my parents move us to an exurb in June, and I start kindergarten in September.

The district we moved to was Holly Area schools. And I thought this meant that Holly schools must be really good schools. And that’s not the case at all. I did well in high school. Once I went from like a rural public school that I now know was underfunded to a private university on the East Coast, I understood real quick how poor my education had been. When I went digging into the history of it, right, the district we had moved to was poor and was underfunded. And was so underfunded that it was not running a full school day and it was in danger of losing its accreditation. So there was no way you would have moved to that district for the schools.

I did interview adults, people who had been adults in the community where I grew up, about the schools and about race in the community. Everybody knew that Holly had a bump in population because white folks were trying to get away from integration in the smaller cities outside of Detroit.

White folks, you know, certainly my parents’ generation and my grandparents, would say, “Oh, well, we didn’t know anything about that.” I think before I reported this book, I would have been pretty credulous about that. And honestly, now I’m pretty angry about it.

“When you join forces across different lines, including across class lines or across race lines, you can get something that benefits everybody and in fact is more than you get for yourself individually.”

Why do you think those topics weren’t discussed in your home or in other white households?

I think white people think racism isn’t about them, right? Which is one of the great sort of tricks of American society. Which is a lie, right? Racism is about white people. And also, if we don’t talk about it, then we don’t have to worry about having to defend the things that we got because of it.

I think a lot of the reason that white folks don’t speak up about racism as white advantage is because we don’t know how to talk about it. We think that if I say anything about this, it’s going to get taken away, right? And the fact is, like, we don’t have to give it up. We just have to share with everybody. And I think that’s been a real stumbling block for a lot of white folks that fear that things will get taken away, as opposed to saying, “I don’t have to give this up, I just have to fight for everybody to have it.”

What do you want people to take from the book?

I would love it if a lot of people came away from it really wondering if racism is worth keeping. Every time white people keep our mouths shut about it, we’re helping it continue. Are the things that we are getting from it worth it? Worth the things that it does to Black and brown folks, and also worth the way that it contorts our democracy and ruins our social safety net?

For me, I just felt like as a white woman, I could not credibly walk around being like, “I don’t think racism is worth it” if I didn’t have some idea of how much it was worth in the first place.

One bright spot that I enjoyed in the book was you speaking about solidarity dividends toward the end. Could you just explain what a solidarity dividend is?

A solidarity dividend is a concept that Heather McGhee developed, which is that we all benefit from collective institutions that work in our favor. When you join forces across different lines, including across class lines or across race lines, you can get something that benefits everybody and in fact is more than you get for yourself individually.

I’ve seen this in my life. I’m a rent stabilized tenant in New York. That has been key to me having the life that I had. There’s no way I would be a writer if I had to pay market rent. And that’s something that was a multiracial coalition of tenants back in the Depression era, when they were first getting rent controls and then preserving a version of it as rent stabilization in the 1960s.

How do we build toward more solidarity, dividends and more support?

The general thing is to build cross-race and cross-class movements.

For folks that sort of take the story and ask, “Well, but what do I do now?” I say, “Well, work to end racism.” That would actually be the thing that’s helpful. I don’t think that means just going to Black Lives Matter protests. I think that means get involved with a union, get involved and push for racial equity in your union because it will make it stronger. Get involved in fights to fix health care, like things like that, really getting involved at the grassroots level to build political power. I mean, that’s the thing that actually makes change.

Tracie McMillan will appear in conversation with author and columnist Erin Aubry Kaplan on May 16 at 6 p.m. at Chevalier’s Books in Los Angeles. The event is free. For more information, go to Eventbrite.com.

Copyright 2024 Capital & Main.