As fans swarmed outside her bus, cheering and waving homemade signs while television cameras rolled, Caitlin Clark realized she was in her pajamas.

She had been so exhausted by her pursuit of a championship that she hadn’t considered what awaited at the end of the ride. After a long few weeks away, Clark was back in Iowa, the only state she had ever called home, a place she had always loved and one that had come to love her back. What she did not initially grasp was just how much that had intensified while she was away.

Clark was returning to the same state but a different world.

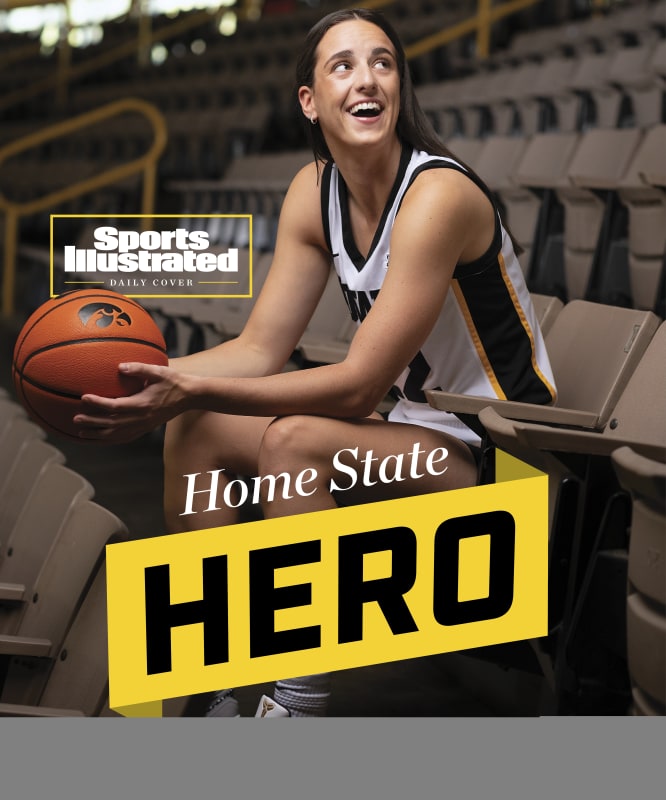

David Sherman/Sports Illustrated

This was the aftermath of the 2023 NCAA tournament for Iowa women’s basketball. An electrifying run had ended in the first championship game in program history, and the driving force was Clark, a junior guard who spent the month turning heads and smashing records. No college player, male or female, had scored as much in one tournament. No one had recorded a 40-point tournament triple-double. (Or, for that matter, a 30-point tournament triple-double.) No one had sunk so many postseason threes. Clark had elevated her play into something that felt closer to grand, jaw-dropping theater. She took what she had been doing for years—no-look passes, shots from the logo, tricky maneuvers in traffic—and delivered on the biggest stage. Clark finished short of a title, with Iowa falling to LSU in the final, 102–85. But she helped secure a new kind of attention: Viewership for the women’s national championship set records and doubled year-over-year. Clark had done something the game had never quite seen under a spotlight it had never quite experienced.

And then the bus came to a stop.

Clark found a simple answer for the moment in front of her. (She pulled a sweatshirt on before signing autographs and posing for pictures in her pajama pants.) But there would be plenty more questions. The 21-year-old’s star had been steadily rising over the past three years, and in the space of a few weeks, it had exploded. She now had to figure out what that meant.

And she’d have time to think about it. Clark has never been one to take a break, ease up, relax in any way. But Iowa coach Lisa Bluder told her after the tournament to take some time off—two weeks, at least, without so much as touching a basketball. This directive was partially for physical recovery. But it was more for her mentally. Before conversation grew too loud about what Clark’s performance had meant for women’s basketball, what it meant for women, period, and basketball, period, Bluder wanted to make sure that Clark had time to process what it meant for herself.

“She needed to do that,” Bluder says. “I really believe that she needed to have that time just to realize what she did, soak it in and be prepared to do it again.”

So for the next two weeks, Clark did not pick up a basketball, and instead she picked up everything that had come home with her. “I felt like I had collected all these NCAA items,” Clark says. “Like a million things from the whole trip.” The cowboy hat she and her teammates got at the Final Four in Dallas. Mementos from their sightseeing at the Sweet 16 in Seattle. As she unpacked, Clark went through every souvenir and scrap of paper, trying to commit the story of each to memory.

“Obviously, I remember the basketball games really well,” Clark says. “But it was all the little experiences in between.”

Those were the parts she wanted to preserve. She wanted to hold on to how it felt to experience this alongside the people she loved most, part of a starting five that had been together for three years, representing the state that had always been her home. Clark had never struggled to visualize how success might look for her on the court. But the rest of this had been harder to imagine.

As her world was getting bigger—as she was getting bigger to the world—she wanted to savor these small pieces.

G Fiume/Getty Images

On a weekday morning early in the fall semester, Clark sits in a nearly empty Carver-Hawkeye Arena. She had spent much of her time this summer in this building—taking hundreds of shots in her daily gym sessions either alone or in small groups. (Off the dribble, cutting to the corners, from half court: As fluid and improvised as Clark’s game can seem, teammates note that she practices everything, with countless reps backing up each of her seemingly magical shots.) That was just like every recent previous summer for her. It was everything else that was different.

In August, Iowa announced that it had sold out the entire women’s basketball season: Demand for season tickets was so overwhelming they could not promise any single-game offerings. The Hawkeyes set a record for Big Ten attendance last year. But this was another level. The program had previously sold out just a handful of games in the 15,056-capacity arena, and now it was packing an entire season months before tip-off.

The mania had spread beyond campus, too: When the Triple A Iowa Cubs gave out a Caitlin Clark bobblehead in June, fans started getting in line at 6 a.m. When she played the John Deere Classic Pro-Am in July, just over the border in Silvis, Ill., organizers couldn’t recall a gallery so large since Bill Murray played in 2015. (At the event Clark was paired with U.S. Ryder Cup captain Zach Johnson, who demurred when asked whether she had the game-changing potential of Tiger Woods but called her “transcendent” and “spectacular.”) And Clark received perhaps the biggest honor of all in August: Her likeness was sculpted in butter at the Iowa State Fair.

“I mean, people go to the fair just to see the butter sculptures, especially the butter cow,” Clark says. “For me to be next to the butter cow, that’s a pretty big deal.” (Previous butter honorees have included Elvis, John Wayne, Abraham Lincoln and The Last Supper.)

The combined effect has been hard to fathom. That’s true not just for Clark, but for her teammates and coaches, too. Iowa associate head coach Jan Jensen has spent her entire adult life in women’s college basketball, 35 seasons, and she is sometimes bowled over by all that had to happen to allow for this kind of spotlight. “We have been working,” she says, “for moments for people to care.”

Clark wanted those moments, too. Shortly after she committed to Iowa, The Gazette in Cedar Rapids asked the five-star recruit out of West Des Moines why she had chosen the school over traditional bluebloods. “Iowa isn’t a program that has always been to the Final Four,” she said, “and I want to help do something different.” If that was an audacious quote for a player yet to step on campus as a freshman, well, Clark has always been an audacious person. And soon, a banner will be raised to commemorate that she did, in fact, do something different.

What she had not realized was how much she would have to change to make it happen.

Clark always chafed at the idea that staying close to home was a sign of modest goals or limited vision. If anything, her path felt more ambitious. Clark did not just want to go to a Final Four. She wanted to do it on her terms, elevating a program she grew up watching, making a team achievement into a state celebration. Clark knew she had options elsewhere. But she wanted this one.

This energy is reflected in her game. Clark regularly attempts moves that might otherwise be classified somewhere between unwise and impossible. Her most striking asset is her range: If shooting from the logo generally conjures images of desperate, last-second heaves, she makes it look so natural as to be downright practical. But what coaches praise most is her vision. The Hawkeyes know to be ready for a pass from Clark at any time—in transition, full court. Nothing is off limits. “She just sees the floor in a completely different way,” says former Iowa center Monika Czinano. That ambition comes with occasional costs. (Turnovers, namely, though Clark has made progress cutting down on those.) Still, it’s a show unlike anything else in college basketball.

So, naturally, Clark’s dreams for the Hawkeyes were bold. But they did not feel as dramatic as they might have a few years before. Iowa had experienced program-shifting progress just before The Clark Era: It graduated two future WNBA picks in forward Megan Gustafson, the program’s first National Player of the Year, and guard Kathleen Doyle. Together, the pair had led the Hawkeyes to their first Sweet 16 appearance of Clark’s lifetime, and, in 2019, they went to the Elite Eight, which Iowa had not done since 1993.

And then came the most-hyped recruit imaginable. Here was a player who came in with big talent and big talk. Her impact was immediate, and until she got to exactly where she wanted, she kept making it bigger. As a freshman, she led the nation in scoring. As a sophomore, she led the nation in scoring and assists per game, something no one had ever done. As a junior, she scored more (27.8 points per game), dished out more assists (8.6), ran the table on national awards and made it to that Final Four. As a senior—put a ceiling on her this year at your own risk. Viewed at a distance, Clark’s time in Iowa coheres neatly into a narrative arc. But the trajectory wasn’t that straightforward.

How do you develop a player who feels like the exception to every rule? What does it mean to shape her without constraining her? And how do you cultivate a team dynamic that can withstand the weight of this much star potential?

“Caitlin is the challenge of a lifetime,” Jensen says. “We’re so fortunate, so blessed, but it’s not easy. . . . You have to know what to do with that strategy-wise but also culture-wise.”

From Clark’s first practice, it was “super obvious her skill level was off the charts,” Czinano says. She was stunned by how directly Clark’s highlight reel translated to a scrimmage, with passes that made her wonder how anyone could find those angles, let alone execute them, never mind as an incoming freshman. But Czinano picked up on something else, too. “There was a lot of growth to be done in the team compartment,” she says. “She’d had to be The Person for so many years that it was apparent that she was going to need to trust us. . . . That takes time when you’re, like, a child prodigy.”

Jensen, who did much of the recruiting work on Clark, remembers seeing this as early as seventh grade. “She’s wired crazy competitive,” she says. “So she’s doing everything. She just hates losing.” Clark’s skill set was incredible. But she wanted to win so badly that she tended to deploy those skills at max effort all the time. And her frustration was obvious when anything went awry. Clark’s intensity was palpable, which could be a great thing, until suddenly it wasn’t.

And so began the defining project of Clark’s time at Iowa: a quest for balance. She had to learn when to take control of a moment on her own and when to hand it to a teammate, when to splash out and when to go for something safer, when to embrace her fire and when to understand it as a liability. The Hawkeyes had to refine Clark. But they didn’t want to break her.

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

This started with developing a greater feel for context on the court. “There were some frustrating moments her freshman year,” Bluder says. “She’d go off-script so much.” In 20 years at Iowa, Bluder had traditionally coached an offense that was high scoring and free flowing, but here was a player who pushed the boundaries. Bluder had no interest in taking away Clark’s creativity. She did not want to (literally or figuratively) limit her range. “A person like Caitlin, who’s special, you’ve got to let them have a little bit of freedom,” Bluder says. But she had to use her talents more judiciously.

For Clark, obsessive about film and stats, this became a puzzle, a problem she could solve. Her shot selection remains unique. (If it goes without saying that she made more threes last year than any player in D-I, know that she made more from beyond 25 feet than several entire teams made beyond the arc, period.) But she’s learned to shift that within the flow of a game. “Understanding time and score, pace, when and why—I’ve seen her grow tremendously,” says Iowa assistant coach Raina Harmon. And the staff has given a little, too. Bluder has come to realize that a bad shot for most anyone else might be the best shot for her point guard.

Clark faced a steeper learning curve in modulating her emotions. “That’s what’s been more challenging, or more time-consuming,” she says. “I’ve put more work into that.” She’s always been competitive: Her younger brother required staples in his head after a game on their basement Nerf hoop during elementary school. (It was an accident, she says, but Colin Clark still has a scar.) When asked about her intensity, teammates cycle through standard responses like golf, cornhole and video games but then move on to activities without any competitive structure. Like, say, a pizza-making class on their foreign tour this summer in Italy.

The result can be supremely fun to watch. Clark’s ferocity has the same theatrical quality as her playmaking. If you boo, Clark will only feed off the energy. (A well-circulated high school video shows Clark going off for 42 points as the opposing student section chants “overrated” at her.) “It’s really enviable,” Jensen says. “She doesn’t second-guess.” And she makes sure everyone knows it.

Yet being demonstrative can also be destructive—say, the occasional technical foul. But there was a less tangible effect on teammates that could be just as detrimental. The guard has always had punishingly high expectations for herself. (Early in her freshman season, Clark recorded Iowa’s first triple-double in five years, only to criticize her performance afterward: “Everybody is going to have off nights,” she said, disappointed with her shooting percentage.) But her personal frustration could spill over to those around her. “You’re just mad at yourself, but your teammates don’t know that,” Bluder would say.

Heading into last season, Iowa’s coaches challenged Clark. “It was getting her to understand that you’re never going to reach your full potential if you’re always playing angry or playing upset,” says Harmon. Clark began to work with a sports performance coach and the team sport psychologist, both one-on-one and in group settings, watching film to pinpoint where emotion crossed the line into visible negativity. And like the work on her gameplay, this was seen as a matter of balance and context, not of trying to erase her spirit completely.

“If this was a guy? He’d be edgy, he’d be great, he’d be confident,” Jensen says. When people have fussed over whether Clark popping her jersey or giving a Michael Jordan–esque shrug is over the top or cocky or (God forbid) unladylike: “No. This kid is golden.”

By the end of last year, Clark was still passionate, but she was noticeably more poised. She’d taken “huge leaps and strides,” says Iowa guard Kate Martin. The championship game sparked a national conversation about trash talk when LSU forward Angel Reese repurposed a hand-waving gesture that Clark made toward Iowa’s bench in the Elite Eight. But amid the endless hot takes that followed was the fact that no one involved seemed particularly upset afterwards. This was just part of the game. Which, of course, was easier to handle after so much attention had been paid to self-composure.

Clark has always been known as a good teammate. Off the court, she’s “silly and goofy,” Czinano says, “like a little sister.” But her development as a leader and facilitator has been striking. Bluder points to her growing assist numbers. And while Clark’s scoring increased once again last season, she did it taking fewer shots. She’s become more sensitive to individual styles of motivation—understanding which teammates appreciate a little heat and which thrive with a softer touch.

“She has passion, for sure, and it can get a little aggressive on the court, but it’s all out of love,” says Hawkeyes sophomore guard Taylor McCabe. “She really, really cares about our program and our team and our coaches. She’s very selfless.”

Clark enters her senior year with the Wooden Award and the Naismith Trophy, the Honda Sports Award and the Wade Trophy, the AP Player of the Year Award and the ESPY for Best Female College Athlete. And she will have one more honor, one she treasures, one that her coaches have finally decided she is ready for. She will be an Iowa team captain for the first time.

Matthew Putney/Iowa State Fair

Clark’s senior season does not have to be her final one. Under the NCAA’s pandemic policy, she has the choice to return for a fifth year in 2024, but she insists she’s genuinely unsure whether she will.

It’s a “really, really hard decision,” she says, one that will depend on her performance this year, the state of the team and the WNBA draft lottery, among other factors. “Either I’m going to be coming back to something that I’ve really loved,” Clark says, “or I could start my pro career, which was my dream ever since I was a little kid.”

She doesn’t have a timeline. But she says that she wants to head into this season treating it like her last so as not to finish with any regrets. It will certainly be different: Czinano has graduated, along with McKenna Warnock, taking away the program’s second- and third-leading scorers and rebounders from last year. That doesn’t mean another deep tournament run will be impossible. (An increased role for sophomore Hannah Stuelke should help: The forward was Big Ten Sixth Player of the Year as a freshman.) But it will certainly be difficult.

The question about when to go pro is not just about her career or her earning potential or when to let one childhood

dream overtake another. It is about when to leave home. Which is tied to another question: Where, exactly, did she come from?

Clark’s first coach was her father, Brent, who insists he did nothing extraordinary with her. He was just as surprised as everyone else in that first co-ed league at the local YMCA. “She just wouldn’t miss,” he says. She’d grown up in a family of athletes in a neighborhood full of boys, constantly tagging along with older brother Blake, who’d ultimately play football for Iowa State. She had to be tough to keep up. Clark pushed that toughness into everything she could find—basketball, of course, but also softball, volleyball and especially soccer, which she played into high school, learning to anticipate movement and see passing angles.

All this produced a singular talent. But Clark did not rise out of nowhere. Iowa as a state has historically embraced women’s basketball, if never quite like this. In 1970, before Title IX, 20% of girls playing high school sports in the U.S. were in Iowa. Many of them played basketball—six-on-six, a fast-paced variation just for girls. This is the game that Bluder first played, and Jensen, and the team’s special assistant, Jenni Fitzgerald. Some of that DNA lives on in the basketball they coach today. Therefore, it lives on in Clark, too. She could have thrived anywhere. But there is something in the way this state was set not just to produce her or to embrace her, but also to shape her.

Soon, Caitlin Clark will belong to the world, a player without much precedent in terms of skill and personality and ability to draw the spotlight. But for one more year, at least, she is Iowa’s. “She’s been great for Iowa,” says Jensen. “But I’m telling you, Iowa has been really great for her.”