PLAYWRIGHT, painter, screenwriter, costume and set designer, children’s author. John Byrne’s CV reads like a list of the occupations of the inhabitants of an unusually talented village, rather than the work of just one person.

Byrne’s dramatic writing includes the TV favourites Tutti Frutti and Your Cheatin’ Heart, and evergreen play series The Slab Boys (inspired by his time, as a young man, grinding paint in the soul-destroying “slab room” of carpet maker AF Stoddard and Co in the late-1950s and 1960s). His extraordinary body of visual art is as breathtakingly accomplished as it is stunningly diverse.

If ever the term “Scottish polymath” applied to anyone, it applies to John Byrne. That fact has never been underlined more emphatically than now, in 2022.

The superb retrospective exhibition John Patrick Byrne: A Big Adventure opened recently at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow (running until September 18). Meanwhile, not to be outdone, the Fine Art Society in Edinburgh, is currently hosting a delightful little exhibition of Byrne’s work (running until July 16), which is cheekily titled Ceci N’est Pas Une Retrospective (an allusion, not only to the Kelvingrove show, but also to the letter written to Byrne by the great, Belgian surrealist René Magritte, which features in both exhibitions).

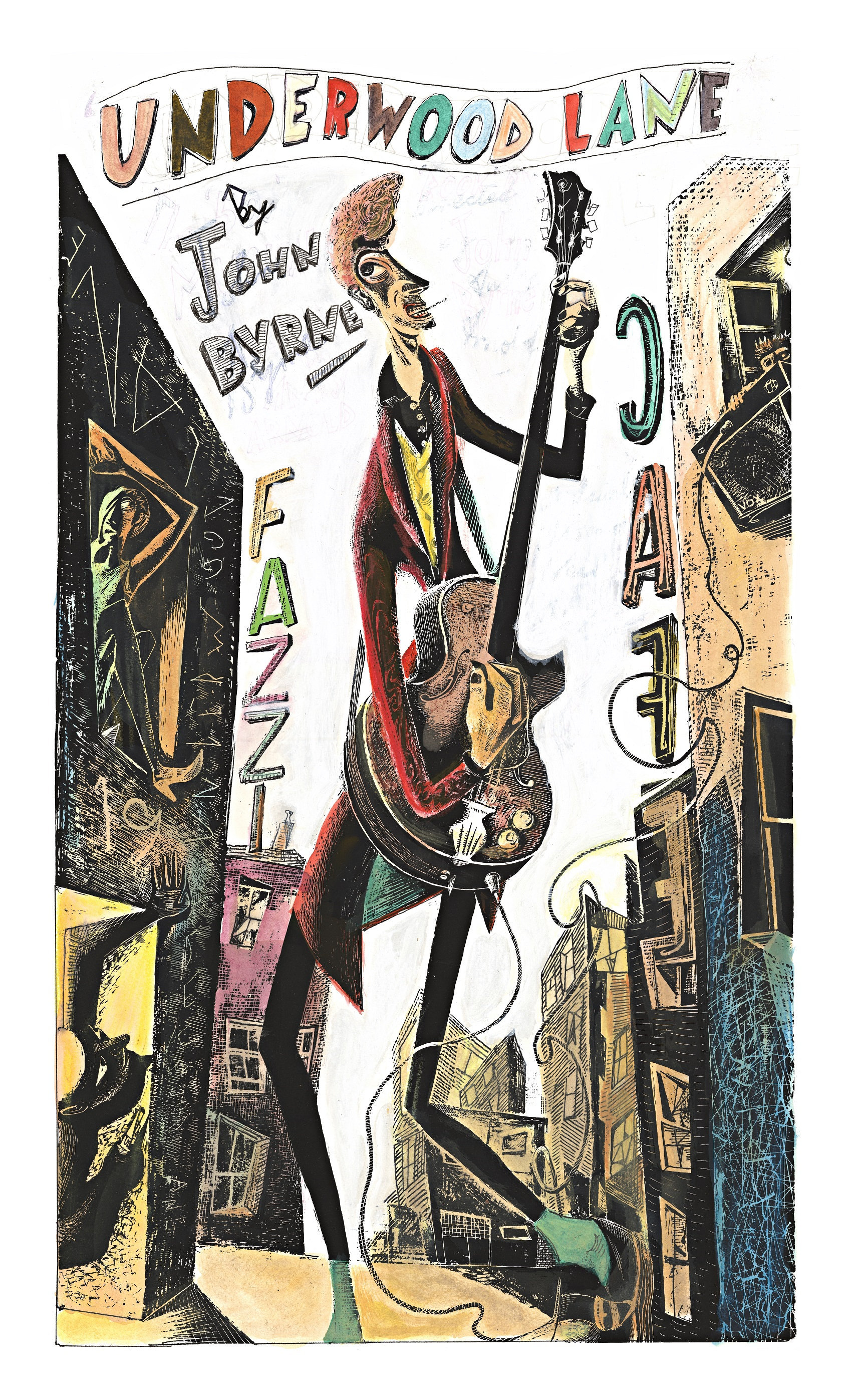

As if that wasn’t celebration enough, in a few short weeks, Johnstone Town Hall and Glasgow’s Tron Theatre will host the world premiere performances of Byrne’s play Underwood Lane (poster below). Dedicated to the memory of Byrne’s late friend, the singer-songwriter Gerry Rafferty (who grew up on the Paisley street of the drama’s title), this play-with-songs follows the travails of a fictional skiffle band made up of young, working-class Catholics in Paisley in the early 1960s.

In truth, it doesn’t seem possible to celebrate Byrne enough. He is that rarest of creatures, an uncompromising, popular artist.

His body of work has made a gloriously original and indelible mark on Scottish society. Not only that, but his artistic output, and indeed his very personality, have played a wonderful ambassadorial role for Scotland abroad.

Now aged 82, Byrne is a Paisley Buddie and, more specifically, a “Feg” (that is someone from the working-class, Paisley community of Ferguslie Park – an economically and socially neglected area throughout Byrne’s post-war childhood, and indeed, ever since). That experience – from his loving, Irish Catholic upbringing in Paisley, to working at Stoddard’s, to the influence of American popular culture on him and his friends – has shaped a remarkable artistic career that spans six decades.

A visit to the Kelvingrove exhibition confirms Byrne as a painter of eclectic brilliance. As his teachers at the Glasgow School of Art are reputed to have observed, Byrne can turn his hand to any artistic style, and be equally accomplished in each one.

He is no “jack of all trades, master of none”. Byrne seems to be able to master any artistic style almost effortlessly (although, no doubt, an extraordinary amount of dedication and hard graft lies behind that seeming God-given gift).

Take, for example, his paintings in the so-called “naive” style. Signed “Patrick”, in homage to his beloved father, pictures such as Owl (1968) and Jock (1967) are wonderfully reminiscent of the work of the master of naive painting, the great Georgian artist Niko Pirosmani.

In the painting Writer’s Cramp (1975) – which foreshadowed his acclaimed debut play of the same name – Byrne paints an obscene, militarised figure with all of the disquieting brilliance of the Weimar German artists George Grosz and Otto Dix. The fabulous room of self-portraits – painted in a dazzling array of styles – includes a Cubist piece (Dollar Point, about 2009, below) that could have come from the brush of Pablo Picasso, save for the hilarious, cartoonish lit cigarette that protrudes from Byrne’s transmogrified visage.

The Kelvingrove exhibition showcases Byrne’s excellence as a draughtsman and his versatility as a stylist (his fine portraits of his former partner, actor Tilda Swinton, and his current wife, the theatre lighting designer Jeanine Byrne, could easily be mistaken for the work of two different painters). The show also testifies to the artist’s personal humour, intelligence, compassion and humanism (as evinced in his decision, rightly highlighted in the exhibition, to return his MBE in protest at the invasion of Iraq).

There is a strong connection between Byrne’s paintings and his dramatic works for stage and screen. One only needs to look at the painting that graces the poster for Underwood Lane.

Neglected and impoverished though Ferguslie Park was (and is), Byrne’s hyper-realist picture fills the titular street, not only with sinister elements and dereliction but also the reflected glamour of rock ‘n’ roll. That beautifully stylised hyper-realism is the hallmark of Byrne’s writing style (which the playwright David Greig calls Byrne’s “idiolect”, a form of Scots-English that is specific to Byrne and his idiom).

When I meet Andy Arnold and Hilary Brooks – director and musical director, respectively, on Underwood Lane – they agree that Byrne has a unique style as a writer. “He’s definitely got a distinctive voice, there’s no doubt about that,” says Arnold.

Like The Slab Boys trilogy, the play attests, the director says, to the “musicality” of Byrne’s writing. It also testifies to the theatrical brilliance of his portrayal of characters.

The figures in Byrne’s plays are “not naturalistic”, Arnold comments. “They’re all slightly larger than life.

“There’s a stylised aspect, which is great for staging a piece like this. It gives you great licence.”

The piece is, Brooks explains, a play-with-songs, rather than a musical, which has “a band at its core.” The band, Arnold adds, could “in some ways… be the young Gerry Rafferty, couldn’t it, and his band when he was a teenager?”

The young Byrne used to hang about with Rafferty’s older brother. The story goes that Byrne had a beaten-up old banjo which he brought into the slab room at Stoddard’s.

Rafferty’s sibling is reported to have said, Arnold recalls, “My brother’s trying to learn to play the banjo, can he borrow that?” The rest, as they say, is musical history.

The music the band plays in the show – rock ‘n’ roll and R&B classics, mainly from the United States in the 1950s and early-1960s – is, Brooks explains, “all John’s favourite songs”. The John Byrne jukebox that is laced through the play includes: Baby I Don’t Care, by Elvis Presley; It’s Only Make Believe, by Conway Twitty; and Crying In The Rain, by The Everly Brothers.

The legions of fans of The Slab Boys can look forward, says Brooks, to a drama that is a “sister play” to the famous trilogy, “rather than a successor”. That is to say that the narrative of Underwood Lane – in which we follow the members of the fictitious band and their travails in love, life and death – is entirely distinct from the adventures, and misadventures, of the denizens of the slab room.

“John would never have one word of overt politics in any of his plays,” Arnold observes. Yet, as in so many of Byrne’s dramas, Underwood Lane carries a political undertow. These characters are working class and Catholic in the west of Scotland in the early 1960s. Whilst the play is very funny, says the director, it also has a sense of its characters struggling to break free from the restrictions that society has placed upon them.

The drama (which has taken 16 years to travel from Byrne’s desk to the stage) is, Brooks comments, “a great ensemble piece, for 10 actors, eight of whom play instruments!” Arnold shares the musical director’s excitement about being able to stage a play with such a large cast (which is a relatively rare occurrence in Scottish theatre these days).

The Tron is only able to afford such a large-scale show, he explains, thanks to the involvement as co-producer of One Ren (the arts and culture arm of Renfrewshire Council). The production will open at Johnstone Town Hall in Renfrewshire, before transferring to the Tron.

Arnold has worked on a number of Byrne plays in the past, including Colquhoun And MacBryde, which traces the lives of the titular artists and lovers. The director remembers reaping the benefits of Byrne’s famous versatility as a painter.

“John just painted all these Colquhoun and MacBryde-style paintings, so we could dress the set with them,” Arnold recalls.

“There’s a moment in the play when we reveal this massive, great Jackson Pollock painting, a huge canvas. [Colquhoun and MacBryde] are looking at it and saying, ‘if that’s the future, we’re finished’.”

The scene raises the question of how the Pollock piece is to be represented on stage. “John said, ‘I’ll sort that for you’,” Arnold recollects. “He came up one weekend and just painted a complete Pollock replica.”

From Picasso to Pollock, by way of Colquhoun and MacBryde – such are the diverse talents of John Patrick Byrne.