It was the retort seen ’round the world, and its origin lay, at least in part, with a player who was more comfortable letting a high-profile teammate send the message.

Guillermo Ochoa had spoken, and the U.S. men’s national team was itching to respond. During the buildup to November’s World Cup qualifier, Mexico’s veteran goalkeeper claimed that El Tri remained the Americans’ primary focus and measuring stick even after two consecutive defeats.

“Mexico has been that mirror in which they [the U.S.] want to see themselves and reflect, what they want to copy,” Ochoa said.

The Americans, who had already won the Concacaf Gold Cup and Nations League finals, took offense. And so before rolling Mexico, 2–0, in Cincinnati, the U.S. players plotted their response. The message was simple: Ochoa had it backward.

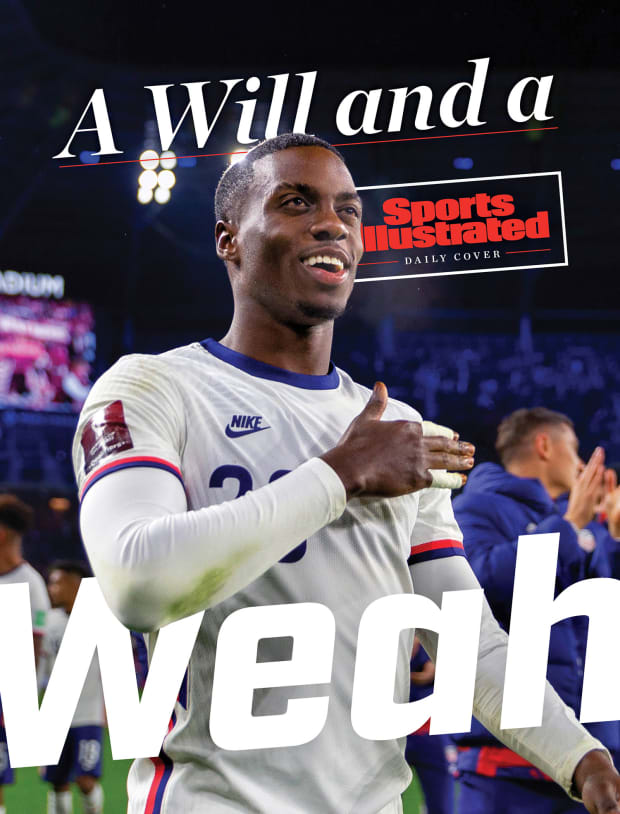

John Dorton/ISI Photos/Getty Images

“I think maybe Christian [Pulisic] was thinking about the same thing at the same time,” Tim Weah recalls. “But myself and DeAndre [Yedlin], we went down to the kit room and we were just making a joke about what they were talking about in the media, etc., and we just joked, ‘What happens if Christian wears “I’m the man in the mirror” on a T-shirt?’”

U.S. Soccer kit man Kyle Robertson whipped one up, and the rest is rivalry history. Pulisic entered the game in the 69th minute, scored five minutes later off a cross from Weah and then lifted his jersey and spread the word.

“It was funny. I think it’s one of our most iconic moments,” Weah says.

But why not wear the shirt himself? Pulisic was recovering from an injury and wasn’t pegged to start. Weah, 21, had shown well in October’s win over Costa Rica and was an integral part of the game plan in Cincinnati.

“Because I’m not that type of guy,” Weah answers. “I just like to be low key and in my own corner—do my own thing. I think Christian was the right player to do it. He’s our main guy.”

John Dorton/ISI Photos/Getty Images

Weah was happy to assist, both on the goal and with the Sharpied rejoinder. He’s comfortable deferring to the likes of Pulisic, a UEFA Champions League winner, even though Weah has been in the spotlight since childhood and has a multinational array of titles on his résumé. He’s thrilled simply to be part of a growing program that refused to leave him behind during a brutal stretch of injuries.

And there’s no reason to add even more weight to what he’s already wearing. There’s no need to draw attention to yourself with a T-shirt when the back of your jersey reads “WEAH.” It’s one of the most famous names in the football world, and it invites plenty of interest, scrutiny, hope and expectation all on its own. Weah surely would be considered soccer royalty if his famous father hadn’t been elected democratically.

“I would never ever call it a negative. I always think in the positive. Having a dad, having someone of that caliber to look up to, is amazing,” Weah tells Sports Illustrated when speaking of his father, George, the only African winner of FIFA’s World Player of the Year award and the Ballon d’Or, a former superstar at clubs like Paris Saint-Germain and AC Milan and now the president of his native Liberia.

“What he’s done is legendary and will always be legendary,” he continues. “It just sets the bar high, and it just makes me want to work even harder. Obviously, you get people who are going to be malicious about the situation and talk bad about you. That’s everyone, just trying to compare me to my dad. I will never be like my dad. I can only achieve what I can achieve.”

A global player of the year award is unlikely. That’s basic math. And reaching national hero or head-of-state status is going to be a tall order for a U.S. soccer player. George Weah has been honored by the United Nations and in 2004, ESPN gave him its Arthur Ashe Courage Award. Many consider him the best African player of all time.

But short of those lofty, singular achievements, Tim’s potential has few limits. He’s clearly got the ability. A versatile attacking talent, the Brooklyn native has the skill, speed, vision and creativity to unhinge a defense from multiple positions (the U.S. has been using him primarily as a right winger in its 4-3-3). He also seems to possess the proper temperament. Weah comes across as a young man devoid of entitlement. He’s eager to earn his birthright and already has overcome his share of obstacles, from long-term injury to the attention that accompanies his name.

Weah’s dexterity on and off the field was worth the commitment from U.S. coach Gregg Berhalter and his staff, who retained faith in the player as he recovered then rebounded from multiple severe hamstring issues. And upon Weah’s return, those qualities have lifted him quickly into a place of importance on this ambitious and historically young national team, which will continue its quest to qualify for this year’s World Cup on Thursday evening against El Salvador.

The core of now familiar American names climbing the ranks at some of the sport’s top clubs coalesced while Weah was injured in 2019 and ’20: Pulisic, Tyler Adams, Weston McKennie, Sergiño Dest, Gio Reyna and more. If Weah’s contributions to Lille’s stunning ’20–21 French Ligue 1 championship didn’t lift him to that level, then his performance during the U.S.’s November World Cup qualifying window certainly sufficed.

Weah made his qualifying debut in October. As an emergency starter in the vital home game against Costa Rica, he created the own goal that lifted the Americans to a come-from-behind 2–1 win. That performance in Columbus—the site of Thursday’s game—plus injuries to Pulisic and Reyna, helped thrust him into the starting XI a month later against Mexico. And he was electric that night in Cincinnati, frequently putting El Tri on its heels before delivering the backbreaking cross to Pulisic. A few days later, Weah scored the only goal in a gritty 1–1 draw at Jamaica, his mother’s homeland. Weah had arrived.

“With Tim, it’s about mentality. When he has it in his mind and he’s set, he can execute all day. And it’s just about him focusing on how he’s going to perform,” Berhalter said during the delirium that followed the win over Mexico.

“He’s a guy who suffered a horrendous injury, [and] getting back from that was difficult,” the manager continued. “And now that he’s back, especially with the national team, now it’s bringing him to that rhythm, continuing to develop him and talk to him about what the expectations are in this environment. But he’s been as open as anyone. … He wants to get it right and he really feels part of this group now, and I think that’s where things start to come together nicely.”

Berhalter’s team has a challenging and critical week ahead: three games in frigid conditions that will leave it somewhere on the continuum between coasting and desperate when the final qualifying window comes around in March. The Americans (4-1-3) are one point out of first place in Concacaf’s eight-team, double-round robin, which will send the top three finishers to the World Cup. But they’re also just a point above fourth, which would mean a nail-biting, one-game playoff in June. The March window includes visits to Mexico and Costa Rica, where the U.S. has never won a qualifier. That perilous schedule enhances the importance of the upcoming matches: Thursday’s against the seventh-place Salvadorans (1-4-3) at Lower.com Field, Sunday’s at first-place Canada in Hamilton, Ontario, and then the finale next Wednesday vs. Honduras in St. Paul, Minn. Three internationals in seven days are a grind, and Berhalter called in his largest qualifying squad yet—28 players—in an effort to manage fatigue, the coronavirus and the weather.

“Everyone knows how big it is,” Weah says. “But I think it’s really important to take it game by game and just stay humble about things—just do what we know how to do best.”

It’s the blueprint for Concacaf qualifying, and for Weah’s rise. It’s so tempting to look ahead and around corners and imagine this young, promising team performing on the world stage in Qatar. The U.S. has already learned, however, that qualifying will trip you up quickly if you’re not fully focused. Pedigree is pretty much irrelevant inside Concacaf’s quirky crucible. It’s also easy to imagine a young player such as Weah being seduced by his proximity to the glamour of the global game. Trophies, wealth and fame weren’t as foreign to him as they are for others. They were in the family. But Weah wouldn’t be where he is now—a player the U.S. will depend on—if he wasn’t willing to strive and suffer.

Pedigree was a benefit at the beginning. Weah’s parents met in New York City and married in 1993. After growing up on Long Island and Queens, with a childhood sojourn in Fort Lauderdale, he moved from the New York Red Bulls to France as a 14-year-old to play in PSG’s academy. His father’s French citizenship, secured during stints with AS Monaco and PSG, paved the way. PSG is an apex predator club, however, and playing time is tough to come by. Tim became friends with Neymar, but he wasn’t going to take the Brazilian star’s spot in the lineup. While on the fringes in Paris and on loan to Celtic in Glasgow, Weah started to accumulate titles—three league championships, a Scottish Cup, etc. Like his father’s honors, however, they were more personal trivia than personal achievement. Weah was still developing and played sparingly.

In 2019, after getting some time with the national team under interim coach Dave Sarachan, Weah moved to Lille, a smaller club near the Dutch border. Although modest compared to the Parisian giants, Lille was coming off a second-place campaign and was adding to a young squad eager to contend. The expectation was that Weah would play meaningful minutes at last. But reality didn’t cooperate.

A series of debilitating right hamstring injuries limited Weah to 86 minutes of action in 2019–20. He got hurt, rehabbed, got hurt again, rehabbed and then got hurt again. For a young man whose dream was repeatedly deferred, the ordeal cemented two invaluable truths: There are no shortcuts to success, and pedigree and ego are no substitute for genuine support.

JB Autissier/Panoramic/Imago Images

“That happening was kind of a test of my mental strength,” Weah says. “It was just a heartbreak. I had to be mentally strong, and I just knew I had to stay focused and get back into work.”

Combined with the pandemic, the injury led to some measure of isolation for a gregarious soccer junkie who feels most at home among friends on the field. Ask Weah about his team—club or national—and he defaults to discussing relationships, human interaction and atmosphere. It’s not that the soccer is of secondary importance. It’s that for Weah, it flows from the former.

“It can really work your mentality seeing your team on the field—seeing them play games and stuff like that, and you’re not able to be out there with your brothers and help them out,” he says. “It was tough. And obviously, when you’re playing, people are seeing you. People are watching you. People are loving you. And then just at the snap of a finger, it’s like no one cares anymore.”

That’s public. Privately, Weah had ample support on his long, anonymous road back. He’s close with his parents, who urged him to stick with it. And, crucially, he never fell off U.S. Soccer’s radar. Even as Berhalter, his staff and GM Brian McBride began to set the course for the national team’s new era, and as a lengthening list of exciting prospects began to accumulate international seasoning, Weah remained connected.

“I can’t even tell you—every single person that works for this federation has been amazing. Consistently sending me messages, checking up on me, checking up with the club. It’s kept my mentality really free and just kept me wanting, kept me hungry, to come back and be with the guys,” Weah says.

"Everyone’s on top of everything. So it makes you feel good as a player to know that you have so many people who care about you and care about your well-being—about you coming back and doing well,” he continues. “That’s also a morale boost. So when I’m in camp, I want to give 100% for them because they’ve done so much for me.”

Robin Alam/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

This has been a common theme among U.S. players in recent months. What this group lacks in raw experience, it compensates with chemistry. Berhalter has built an environment that players want to be a part of, and that in turn fuels a generation that appears to be inspired by camaraderie and supportive surroundings. They’re more likely to accept different roles and responsibilities, and rise to the occasion when called upon, when they feel part of something meaningful and validating. Not everyone is happy all the time, but player after player suggests in interview after interview that intangibles are one of this U.S. national team’s strengths. Those bonds are strengthened digitally during the season and in person when possible. Weah spent some of his summer showing teenage midfielder Yunus Musah, who was born in the U.S. but moved to Italy soon thereafter, around their native New York City.

“With this group, we’re all pretty much young, and with that being said, it’s like a real brotherhood,” Weah says. “I think because we’re all around the same age, we really jell together well. Number one, there’s no egos in the team. Everyone’s a team player. Everyone’s happy for each other when someone’s doing well. I feel like that energy and that vibe is amazing.”

Weah finally healed and was a key contributor to Lille’s championship last season, making 28 Ligue 1 appearances and scoring three goals as Les Dogues beat PSG by a point.

“I hold this one closer to my heart because obviously I contributed way more than the other titles that I have,” Weah says.

Watch CONMEBOL World Cup qualifying online with fuboTV: Start with a 7-day free trial!

Weah earned his first national team minutes in two years in November 2020, then he entered as a sub in June’s wild Nations League win over Mexico. After missing the September qualifiers and coming up big in November, he suffered a quadriceps injury last month. The race was on to be fit for Thursday.

“I don’t really have PTSD,” he says. “Whenever I get hurt, I don’t really think much about it. I just think about what’s next.”

Weah made it back to start for Lille last Saturday. Speaking to media Wednesday afternoon, Berhalter said, “Timmy looks great. He’s worked extremely hard getting back. … [He’s] at a great point and we’ll look forward to seeing what he can do this window for us.”

Look forward, but not too far. That’s been Berhalter’s mantra since the U.S. stumbled to a 0-1-1 start in qualifying. Don’t think about Canada and star striker Jonathan David, Weah’s good friend, Lille teammate and fellow New York native. Don’t think about Honduras, the March trips to Costa Rica and Mexico or the World Cup in November. Focus on “what’s next.” It’s like rehab. Pondering months of physical therapy and lonely gym sessions, not to mention an escalating number of DNPs, will break you.

So, “you wake up in the morning, you come in, you eat breakfast and you do your work,” Weah says. Don’t worry about being left behind. Don’t lament the distance between where you are and where you hope to be. Don’t let someone or something else, from skeptics to your father’s résumé, determine your destiny.

“Two years ago, that was always my mindset—to just continue working and continue working to come back with the team,” Weah says. “I was hoping for great performances and good games and fast forward to the present day, [the November] window was definitely that. That’s why I always say it’s a blessing.”

Buzzi/Imago Images

George Weah can look forward, however. If anything, following Tim’s career offers some respite from governing. The elder Weah, now 55, has attended the World Cup only as a spectator (he took Tim to the 2010 final in South Africa). Liberia’s national team program was so frail that Weah famously financed it himself. And the Lone Star still nearly qualified in ’02. But Weah’s fate was to be included toward the top of every list of the greatest players who never made it to a World Cup, alongside the likes of Alfredo Di Stéfano, George Best and Ryan Giggs.

Tim Weah can’t quite wrap his head around the idea that he’s on the cusp of achieving something his legendary father didn’t.

“We talk about this every time. Anytime I talk with my dad, he’s always talking about things I did that he never did. And I’m just like, ‘This guy’s crazy,’” he says with a laugh. “He won the Ballon d’Or! He’s one of the greatest to ever play! But one of his dreams was to take his country to a World Cup, and I feel like now that I’m playing, I just want to give it my all to hopefully, hopefully make that dream come true.”

He can remain “low key,” fit in and be just one of the boys only to an extent. If Weah isn’t technically soccer royalty, he’s at least the guy whose father might wind up watching a World Cup game in Qatar from a FIFA suite rather than U.S. Soccer’s family section.

“They have protocols, so he’s in the president’s box,” Tim explains.

Nothing about Weah’s journey has been normal. But it’s brought him to this moment, to Columbus and to a point where he’s finally taking his place among what he calls the U.S.’s “golden generation.” His path and his play are catching up to the promise of his name. And now, with a few more “great performances and good games,” he’s in position to add to an already significant family legacy.

“That’s another reason why I want to hopefully qualify for the World Cup one day, is to make my dad happy,” Weah says. “Make him proud so that he can say, ‘My son did that.’”