Sorry may be the hardest word — but obviously changing the Australian constitution is even harder.

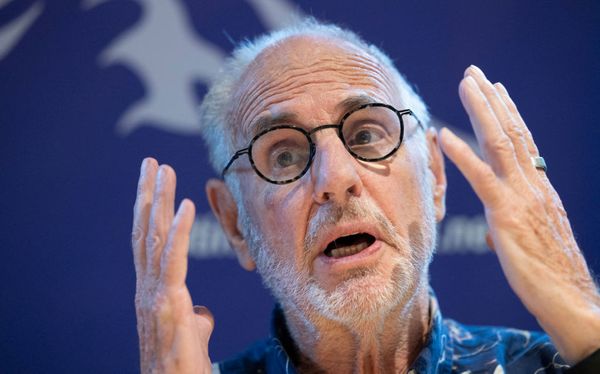

Former Kevin Rudd speechwriter Tim Dixon, who helped write the 2008 Apology to Australia’s First Nations peoples, is watching keenly as Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and his team work to convince voters to say Yes to an Indigenous Voice to Parliament.

“It’s interesting, because there is a parallel there — they’re not the same thing. It does feel like a natural evolution,” Dixon told Crikey. “The difference between 2008 and 2023 is politics is more polarised. And the fracturing of the media environment means that outlets tend to cater to the more highly engaged and more hard-line groups.”

Dixon also said he felt there was less diversity and “fewer liberal voices” inside the Liberal Party this time around than in 2008 when the Coalition reluctantly offered bipartisanship for the Apology.

“The [Liberal] Party did debate the Apology, as Dutton represents — he was one of the guys who didn’t support it — and likewise, they weren’t that far from supporting the Voice. Just look at half of the state Coalition leaders who support it,” he said.

“But part of the difference now is that the base of political parties are more polarised and the Liberal Party in particular is struggling with branches that are just significantly more extreme and hard-line than most Liberal voters.”

In the 15 months since Albanese was elected on a promise of calling a referendum on the Voice, support for the proposal has decreased.

Dixon said the solution to Albanese’s problem was to get specific and concrete to try to reach the “vast majority of people who are disengaged” with politics.

“The challenge is to point to the really concrete benefits of the Voice and reach the significant number of Australians who haven’t really made up their minds and are cautious — not politically conservative — but just cautious about change, and who don’t want us to do the wrong thing,” he said.

“For example, there is a problem [particularly among First Nations peoples] with rheumatic heart disease. We’ve been talking about it forever, but we don’t make progress on it, because those voices aren’t being heard. And you’ve got all these government bureaucracies but they’re not likely to change that.

“Or look at Juukan Gorge, where Rio Tinto blew up really important, historical rock paintings. Why did that happen? There was a local group there that had been fighting that issue for years.

“If you’ve got a Voice, you have a better mechanism [to deal with it] … I think in some ways, the strongest argument is: governments and bureaucracies keep failing. This is about giving the voice directly to Indigenous people — let’s cut through the bureaucracy. That would resonate with a lot of Australians.”

(Albanese might have recently made it harder for himself to use the Juukan Gorge argument, should he wish to — in the past 24 hours, he’s been pilloried for wearing a custom Rio Tinto shirt, helpfully marked “Anthony” on the chest pocket, during a tour of a Western Australian mine.)

In Dixon’s view, the challenge of reaching the politically disengaged explained why many recent conservative campaigns had succeeded where progressive ones had failed: “Because they are more attuned to the concrete reality, rather than concepts and ideas.”

Dixon spoke to Crikey ahead of an episode of the SBS show Insight, airing tonight, focused on the power of apologies, political and otherwise.

Dixon saw Rudd’s 2008 speech as a unifying moment that allowed Australia to begin moving forward.

“I think what we did was talk to the whole country in a way that was honest about the brutality and horrendous injustice of the Stolen Generations, but also kind of doing that in a way that could resonate with everybody, without abandoning every positive thing about Australian history,” he said.

He remembered the time spent preparing for the speech as “incredibly chaotic”: “A lot of people were involved … and also we had just come into government [months before]. I think from memory I had five speeches to write for that day.

“And Kevin Rudd’s style is always being kind of last minute — I think we went to Parliament at nine in the morning, and I was still making changes at quarter to eight.

“Most things in Rudd’s prime ministership were done somewhat by the seat of his pants, because he really did cram, like a student waiting until the last night. That was part of his undoing in the end because he burnt out too many people and his cabinet ministers.

“But I think in this instance [it worked] because of all the other work done beforehand and because he had emotionally engaged and had meaningful encounters with people who had been separated from their families.

“I think that’s why it worked, but in the end, it’s not about the prime minister. The significance is the milestone it represents for the country.”