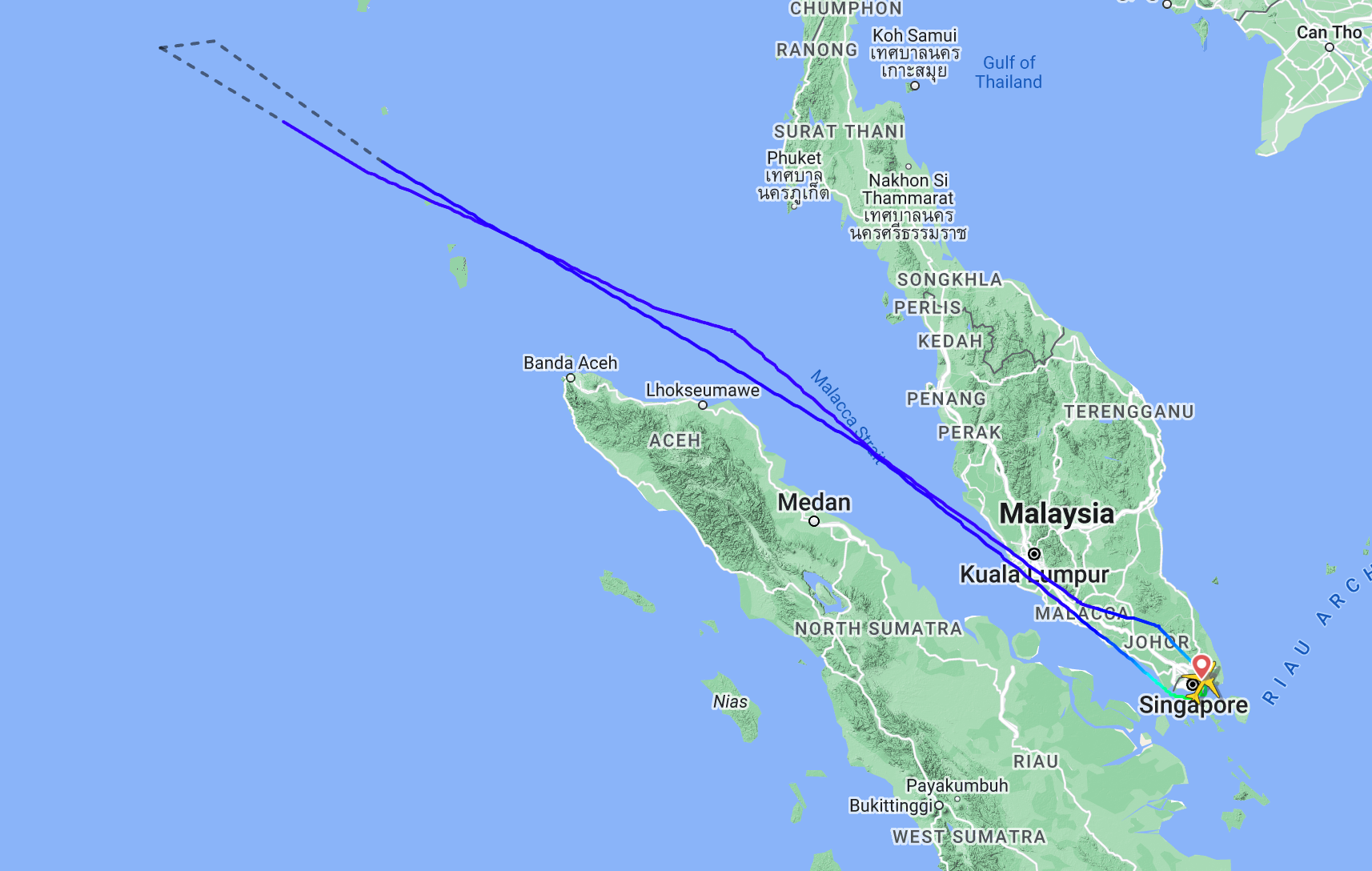

A British Airways flight from Singapore to London Heathrow hit such severe turbulence over the Bay of Bengal that the plane had to return to its starting point where possible damage was checked. Several BA cabin crew were injured in the incident in the early hours of 16 June.

One newspaper report was headlined: “We were in freefall for 1,000ft.” That did not happen.

But just how dangerous is turbulence – and is it getting worse? These are the key questions and answers.

What happened in this incident?

British Airways flight BA12 was flying normally from Singapore to London Heathrow on Friday 16 June across the Bay of Bengal, midway between Sri Lanka and Thailand and about two hours into what was expected to be a 13-hour flight. About 260 passengers were on board.

The Boeing 777-300ER was cruising at a ground speed of 598mph at an altitude of 30,000ft when it encountered severe clear-air turbulence (CAT). While the seat belt signs were on, meaning passengers should all have been strapped in, cabin crew were active.

Several members of cabin crew were injured. The captain decided to return to Singapore, which it did at an altitude of 29,000ft; this may account for some of the reports that the aircraft “fell” 1,000 feet, even though it will have been a controlled descent.

The plane landed safely just after 3am local time and was checked for structural damage, while medical care was arranged for the injured. The aircraft later positioned (flew without passengers) to its base at London Heathrow.

What does British Airways say?

“Safety is always our priority and we’re looking after our crew after one of our flights experienced a rare episode of severe turbulence. Our highly trained team on board reassured customers and the aircraft returned to Singapore as a precaution.

“We’ve apologised to customers for the delay to their flight and provided them with hotel accommodation and information on their consumer rights. We’re rebooking customers onto the next available flights with us and other airlines.”

What is clear-air turbulence?

The US National Weather Service says: “Turbulence is caused by abrupt, irregular movements of air that create sharp, quick updrafts/downdrafts. These updrafts and downdrafts occur in combinations and move aircraft unexpectedly.”

The Federal Aviation Administration defines clear-air turbulence as “sudden severe turbulence occurring in cloudless regions that causes violent buffeting of aircraft … CAT is especially troublesome because it is often encountered unexpectedly and frequently without visual clues to warn pilots of the hazard.”

How much danger was the aircraft in?

The experience was doubtless highly alarming and uncomfortable for passengers, but turbulence at high altitude does not bring down modern commercial jet aircraft.

Planes are designed and tested to withstand severe forces, and weather radar is good at avoiding the worst visible turbulence. But injuries on board an aircraft are alarming – with cabin crew particularly vulnerable.

Writing for the British Airline Pilots’ Association (Balpa), former pilot and flight safety specialist Steve Landells says: “The injuries we see tend to occur when people aren’t strapped in. This may be because the turbulence is encountered without warning but we also see quite a lot of people hurt because they don’t obey the ‘fasten seat belt’ instructions.

How often does this sort of incident happen?

One study suggests aircraft encounter severe clear air turbulence at least 790 times a year, which works out at once every 11 hours. But climate researchers say the incidence at a typical point over the North Atlantic increased by 55 per cent between 1979 and 2020.

According to Paul Williams, professor of Atmospheric Science in the Department of Meteorology at the University of Reading, a doubling of carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmosphere would increase the average amount of severe clear air turbulence at 36,000 feet over the North Atlantic by 149 per cent.

As a result, hazardous turbulence on commercial flights could increase to five serious cases a day on average.

Environmentalists will say that airline passengers are causing the very problems that they are alarmed about – since aviation contributes to the amount of carbon in the atmosphere.

Should passengers worry if they’re planning a flight?

No. You would be extremely unlucky be one of those 790 annual cases; severe turbulence affects only one departure in 50,000.

If the science is correct, the numbers will increase – but only slowly. Passengers should already be taking precautions about the risk of hitting turbulence – the most basic of which is keeping your seatbelt at least loosely fastened whenever seated. (In any event that is good practice because it means the crew don’t have to wake you up if the seatbelt sign goes on).

Steve Landells of Balpa says: “Don’t be tempted to get up when the captain has told you to strap in; we are always talking to the pilots of aircraft ahead of us and, even if it is smooth when we put the signs on, we may know it is going to get bumpy soon.”

In my experience, if the pilot instructs the cabin crew to strap in, you know you’re in for a particularly lively ride.

What’s the worst turbulence you have encountered?

Both while flying over south-east Europe: a small Airbus flying from Vienna to Cairo, and a very large Airbus flying from London Heathrow to Singapore. On both occasions it was very uncomfortable. I’d liken it to a theme-park ride in which you keep going round and round without a chance to get off.

It was made all the most disconcerting because the pilots did not fully explain what was happening and why, and what – if anything – they were doing about it. (Neither flight was on British Airways – the carriers were Austrian Airlines and Singapore Airlines respectively).

There have been a lot of storms lately – what happens if a plane is struck by lightning?

Aircraft should be in no danger. Steve Landells of Balpa says: “When an aircraft is struck by lightning, the energy within the lightning is kept on the outside of the fuselage either by the metal that the aircraft is made of or, in the case of modern composite materials, by a metal mesh that is built into the skin.

“This allows the lightning to track around the aircraft to a point where it can be discharged into the atmosphere. On occasion, some energy from a lightning strike will not stay on the outside so all electrical components within the aircraft are shielded against lightning and it has been many, many years since lightning caused an airliner to crash.”

What other sorts of weather changes might impact flying in the future?

Storms: already this summer they are causing very large numbers of cancellations, with easyJet grounding around 100 flights to and from London Gatwick on Sunday 18 June alone – blaming “adverse weather conditions”.

High winds: these cause problems mostly on take-off or landing. Particularly on crosswind landings, of the sort that happened in February 2022 with Storm Eunice creating some spectacular scenes at Heathrow – but also causing diversions, with implications for passengers and airlines.

Flooding: as we saw at Gatwick over Christmas 2013, when hundreds of flights were cancelled on 24 December. In addition, a number of airports are very close to the sea, and rising sea levels could cause problems – as could storms that bring waves onto the runway.