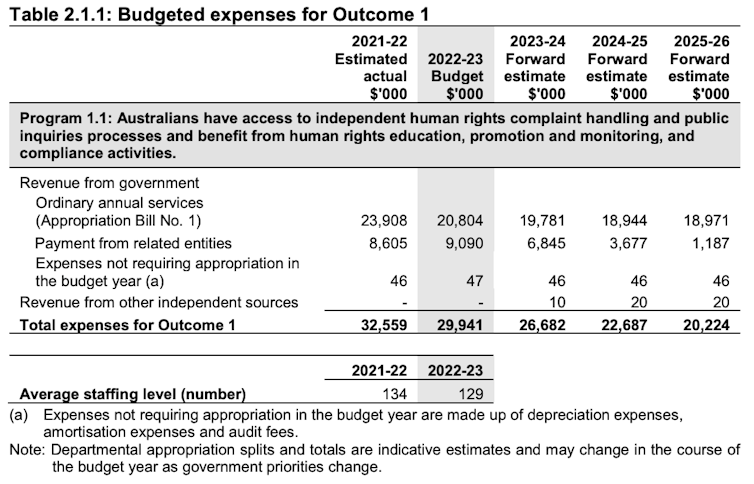

The budget for Australia’s national human rights institution, the Australian Human Rights Commission, will fall significantly over the next four years.

These cuts are outlined in the budget statements from the attorney-general’s portfolio:

These budget cuts couldn’t have come at a worse time, for two important reasons.

Read more: A cost-of-living budget: cuts, spends, and everything you need to know at a glance

The Australian Human Rights Commission is already struggling

First, the commission is already struggling.

Earlier this month its president, Rosalind Croucher, reported the Australian Human Rights Commission was already severely underfunded to perform its statutory functions.

The commission is an independent statutory agency, established by Commonwealth legislation. It has many responsibilities related to its core purpose of protecting and promoting human rights in Australia and internationally. These include:

the investigation and conciliation of discrimination complaints

law reform advocacy

human rights education, and

monitoring of Australia’s human rights performance in the context of its international legal obligations.

Even before the budget, Croucher expected the Australian Human Rights Commission would need to reduce its staffing by 33% to operate within budget.

Over the course of the pandemic, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of complaints made to the Australian Human Rights Commission.

The Australian Human Rights Commission’s 2020-21 annual report noted growing capacity constraints in dealing with this increase in complaints within its allocated budget.

Australia is already distinguished from like countries by its lack of comprehensive domestic human rights protection. This heightens the significance of the commission’s work.

Most Australians have very little recourse to complaints for human rights violations beyond the Australian Human Rights Commission.

Australia has committed to strengthening human rights institutions

Secondly, cutting the Commission’s resources affects more than its capacity to address complaints.

In 1993, the UN General Assembly resolved principles relating to the status of national human rights institutions, known as the Paris Principles.

These are minimum standards for the independent operation of national institutions. Australia has been committed to upholding them through the Australian Human Rights Commission since the principles were first agreed.

The principles say, in part:

The national institution shall have an infrastructure which is suited to the smooth conduct of its activities, in particular adequate funding. The purpose of this funding should be to enable it to have its own staff and premises, in order to be independent of the government and not be subject to financial control which might affect its independence.

This provision indicates that independence from government is essential to the status of a national human rights institution.

The Attorney-General’s department website notes the Australian Human Rights Commission is accredited as an “A status” institution, meaning that it is fully compliant with the Paris Principles.

An organisation known as the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions is responsible for that process of accreditation. It will review the Australian Human Rights Commission’s status this year, and may be compelled to downgrade it to “B status” as only partially compliant with the principles.

That’s because the commission faces a range of threats to its standing and independence, on top of the budget cuts.

In recent years, the Australian government has more than once handpicked a new commissioner for the Australian Human Rights Commission, rather than complying with the obligation to run a transparent, merit-based appointment process.

Former Australian Human Rights Commission president Gillian Triggs was subjected to extraordinary attacks from government ministers – including former prime minister Tony Abbott – particularly in response to a report it released criticising the treatment of children in immigration detention.

Former attorney-general George Brandis was later censured by the Senate over his failure to defend Triggs or the independence of the commission, and for trying to induce her to resign as president.

As she left office, Triggs called the government “ideologically opposed to human rights”.

All of these developments undermine a central pillar of Australia’s voluntary commitments to the UN Human Rights Council, when it commenced its first ever term as a member state on that body in 2018.

Australia pledged to build capacity and strengthen national human rights institutions, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region.

Twin crises

The Australian Human Rights Commission now faces twin crises of insufficient funding and threats to its global standing. The potential consequences are not only reputational.

If the Australian Human Rights Commission is downgraded to a “B status” institution, it will lose its right to vote or hold office in the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions.

It will be restricted to observer status before the UN Human Rights Council, and stripped of its current independent participation rights across UN human rights institutions.

Having made an historic commitment to human rights leadership through its 2018-20 Human Rights Council term, Australia is increasingly sending an opposite message at home regarding its interest in the protection and promotion of human rights.

Since this article was first published, The Conversation received the following comment from the office of the attorney-general, Michaelia Cash:

As is the case with most agencies, funding varies over the forward estimates due to time-limited projects that are funded at particular points.

The reductions in the “ordinary annual services” funding relate to terminating measures that fund the Commission to:

* the completion of the Parliamentary Workplaces Review (ending in 2021-22)

* support the Age Discrimination Commissioner in delivering on her key priorities as part of the aged care reform agenda (ending in 2022-23)

* support business to respond and support people who may wish to come forward with historical complaints of sexual harassment (ending in 2023-24).

The appropriation of the Commission to perform its core functions is more or less steady over the forward estimates.

Any suggestion that the conclusion of a time-limited project amounts to a cut in the AHRC’s budget does not accord with the basic tenets of accounting and gives the perverse incentive to have finitely timed projects with infinite resources.

Read more: Josh Frydenberg’s budget is an extraordinary turnaround – but leaves a $40 billion problem

Amy Maguire does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.