The Government is committed to a target of getting investment to 2 percent of GDP as a way to 'help build a high-skill, knowledge-based and more productive economy'. This is not a Budget to get us there.

The science-related Budget numbers have plenty of noughts. There is $400 million to build three “multi-institution research, science and innovation collaboration centres” in and around Wellington, and $51 million to run them over the next four years.

There is $55.3 million for research fellowships and an applied doctoral training scheme, which the Government hopes will fund more than 260 researchers and PhD students.

There’s $37.6 million for New Zealand researchers to work on global challenges like climate change and health alongside the Horizon Europe Initiative – the EU’s €95.5 billion funding programme for research and innovation.

READ MORE: * Budget 2023: Climate fund slashed by $800 million * ECE expansion, prescription changes in 'pragmatic plan * Childcare boost to ease burden, but not yet

And there’s a 5 percent increase in funding for tertiary tuition from 2024, a little ahead of forecast inflation for next year and “the biggest increase in at least 20 years”, according to Education Minister Jan Tinetti.

It sounds good, but is it enough?

That depends a bit on what your goal is.

If the aim is to help stem redundancies which “are continuing to wreak havoc across our university sector in particular”, as MacDiarmid Institute co-director Professor Nicola Gaston puts it, the 5 percent tuition funding boost is a “massive relief”. The money won’t go directly into science and research, but should provide some security for staff, including researchers, Gaston says.

On the other hand, as University of Otago acting vice chancellor Professor Helen Nicholson points out, this is the sixth year of no funding boost for the Performance Based Research Fund, a more relevant measure of support for science and research in the universities.

“[The 5 percent tuition increase] must be viewed in the context of an ongoing lack of additional investment in the key research funding streams that are so important to Otago, and our researchers.”

There are other positives. Dedicated fellowships and awards for Māori and Pacific people are welcome, says Professor Travis Glare, director of the research management office at Lincoln University, as are boosts to provision of Mātauranga Māori in the tertiary sector, and applied postdoctoral fellowships.

"There are also specific increases in funding for PhD and research fellowships, which will improve the pathway for emerging researchers. Again this is welcome, but there needs to be a similar increase in research funding to allow these newly trained researchers to continue with their careers.”

How about the three new multi-institution research hubs set up to tackle climate change and disaster resilience, health and pandemic readiness, and technology and innovation?

Research, Science and Innovation Minister Ayesha Verrall says they will “bring scientists closer together to increase collaboration, ensure better use of expensive equipment and facilities, and position New Zealand to meet complex challenges and seize economic opportunities.”

Hopefully that will be the case, but still, for researchers there’s the fact that the biggest sum in the Budget – $400 million – will be spent on physical assets, not people. Existing facilities, some of which are sorely in need of an upgrade, will get it, and there will be new buildings and equipment.

But the Budget contains much less direct investment into research operations – maybe $140 million, of which $80 million could simply be money redirected from the National Science Challenges, which finish in June next year.

"I remain unclear as to exactly to what extent this Budget has moved the dial." - Professor Nicola Gaston, MacDiarmid Institute

“This is simply not enough,” the MacDiarmid Institute's Nicola Gaston says, particularly if we want to move the dial on a critical measure in the research, science and innovation world: total investment in research and development as a proportion of gross domestic product, or GDP.

There's plenty of international research which shows R&D is good for the economy of a country and the wellbeing of its citizens. From medical breakthroughs to cool new products you can sell overseas, research tends to lead to better goods and service and more efficient production.

Which is why, in the late 2010s, the Government set a target of raising the total amount of research, science and innovation funding in New Zealand from 1.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) to 2 percent, by 2028.

“This is expected to help build a high-skill, knowledge-based and more productive economy,” it said.

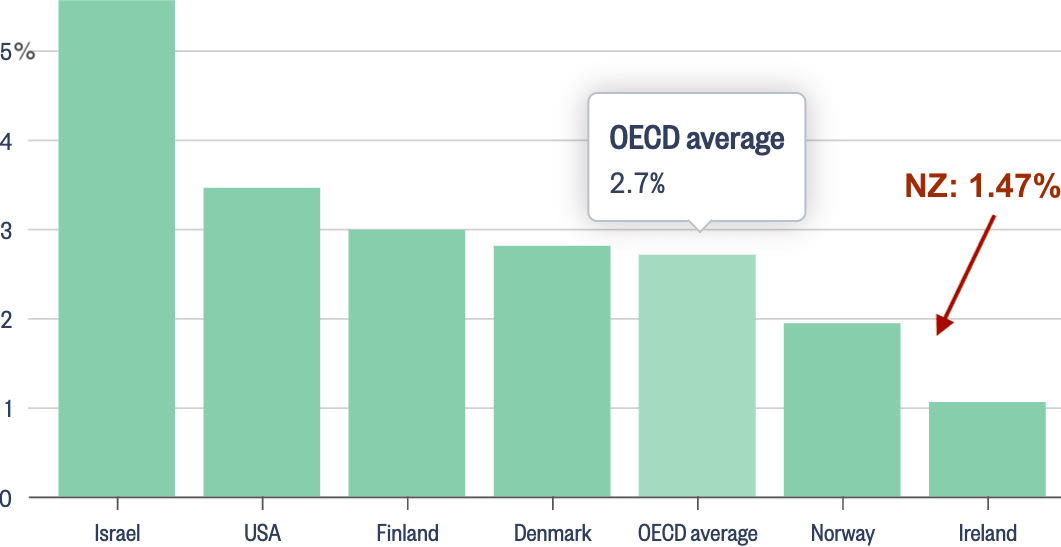

At that time, the OECD average was just under 2.4 percent.

Five years later, the most recent Stats NZ figures show total NZ R&D expenditure as a proportion of GDP was 1.47 percent in 2022, a tiny increase from 1.46 percent two years earlier. By then, the OECD average was 2.7 percent.

Research and development expenditure (% of GDP)

The 2 percent of GDP target is still in the 2023 Budget; in fact it’s mentioned twice, including in the investments section: “Budget 2023 includes significant investments in research and development to deliver on the Te Ara Paerangi Future Pathways reforms of our public research system, consistent with our commitment to increase research and development expenditure to 2 percent of GDP.”

Te Ara Paerangi Future Pathways is the Government’s reform programme for public sector research, science and innovation – a White Paper was released in December 2022.

The target is still there, but the timeframe is not.

That's more like a $600 million budget hole hole, Gaston says, and puts New Zealand four years behind in terms of the $150 million a year increase needed to hit 2 percent of GDP.

Gaston says she’s “very relieved” to see the commitment to getting to 2 percent in the document. “However I remain unclear as to exactly to what extent this Budget has moved the dial.”

She refers to what opposition parties love to call a 'budget hole'. In 2019, MBIE estimates released by the National Party suggested Government spending would need to rise by at least $150 million each year to get to the 2 percent of GDP target, while at the same time business expenditure on R&D needed to increase by 10 per cent each year.

The Government was already behind, National’s research, science and innovation spokesperson, Dr Parmjeet Parmar, said at the time. Now it’s worse, not better, Gaston says.

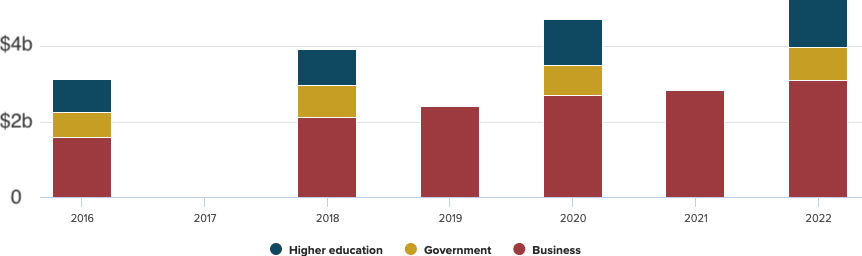

Stats NZ figures suggest over the six years from 2016 to 2022 Government R&D spend went from $658 million to $900 million. That's more like a $600 million budget hole hole, Gaston says, and puts New Zealand four years behind in terms of the $150 million a year increase needed to hit 2 percent of GDP.

Over the same period, business R&D expenditure went up from $1.6 billion to $3.1 billion – not far off the 10 percent a year increase MBIE suggested was necessary. The 2022 figure, for example, was 9 percent higher than 2021.

Research and development expenditure by sector (2016-22)

At the same time, Government spend towards the 2 percent target is going backwards, Gaston says, and that’s seeing emerging and established scientists leave their research – or their country.

“It makes me sad, because there’s a massive opportunity cost in not getting this right,” Gaston told Newsroom after the 2023 Budget announcement. “So many people understand what needs doing and it fails to happen. It’s clearly understood that investment in R&D ads economic productivity, so it will pay for itself.”

She points to a sentence in the Te Ara Paerangi white paper which says: “The research, science and innovation system is not well-placed to absorb the increased funding that is necessary to prepare us for the future”.

That’s the Government calling for structural change in the R&D sector before, it says, it can put significant investment in.

Gaston says that’s ‘cart before the horse’ thinking.

“We need to get money into the system to support people – that’s the ‘capacity’ the Ministry white paper blames us for not having.”

She challenges Government’s statement that 2 percent of GDP is an “ambitious target”; instead Gaston thinks we should be aiming for at least the 2.7 percent OECD average – if not higher.

“When I think of the specific challenges New Zealand faces, it’s like [founding MacDiarmid Institute director] Sir Paul Callaghan said, we have a critical mass problem.

“There are a lot of areas of research where the effort we put in needs to scale with the size of our country, not the size of our population.”

When New Zealand loses scientists, it can be hard to rebuild capacity and capability, Gaston says. “We need to be over-delivering against the OECD average.”