For US tech entrepreneur Steve Johnson, the sentencing of an Australian national for killing his brother Scott in a gay hate crime in 1988 brings an end to a “long and tortuous” pursuit for justice.

Scott Phillip White, 52, was imprisoned for nine years, six without parole, in the New South Wales Supreme Court in Australia on Thursday local time, nearly 35 years after he pushed Scott Johnson over the edge of a 60-metre cliff.

In handing down the sentence, Justice Robert Beech-Jones said White “left Dr Johnson to die”.

“He had everything to live for,” the judge said.

In December 1988, Scott’s naked body was found at the bottom of cliffs at North Head, in Sydney’s northern suburbs, a known meeting spot for gay men.

The 27-year-old’s death was initially ruled a suicide, and it was only after three inquests, a $2m reward, and a diplomatic intervention from the late Senator Ted Kennedy, that Australian authorities were able to make the crucial breakthrough that led to Scott’s killer.

The sustained pressure campaign led by Steve Johnson also forced Australian authorities to hold a reckoning on their own bigoted past.

In 2020, White was arrested and charged with Scott’s murder after being caught in a police sting operation on a secret tape admitting to fighting with him at the clifftop. He later pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of manslaughter.

After Steve Johnson had exposed shortcomings in the initial investigation by police in the Australian state of New South Wales, his brother’s death was linked to dozens of grisly homophobic killings carried out in Sydney in the 1980s and 90s.

It later emerged that as many as 80 gay men were murdered by gangs of teenage boys and men, motivated by a “bloodlust” and hatred of their sexuality.

Hundreds more were beaten, robbed and tortured. Many victims didn’t bother reporting the crimes to police, who routinely turned a blind eye to gay bashing.

Steve’s quest for accountability, and antagonistic relationship with New South Wales police, is credited with helping to expose anti-gay bigotry among law enforcement in the 1980s.

Today, the city is home to the largest gay festival in the world, the annual Sydney Mardi Gras held in February.

The killing of Scott Johnson

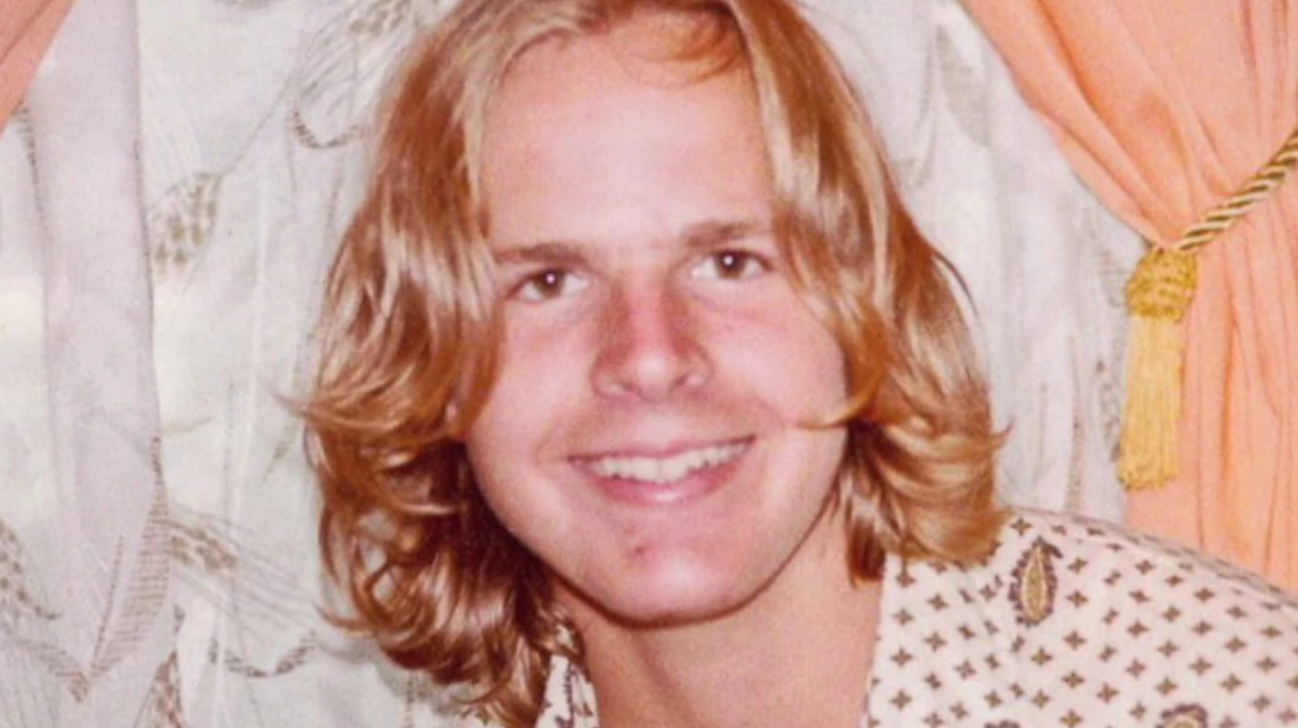

Scott Johnson had been dealt a tough start to life. Los Angeles born-and-raised, his parents split and he’d found his escape from poverty and the family’s regular relocations by reading JRR Tolkien and listening to classical music, his older brother Steve would say.

He showed an aptitude for mathematics from an early age, in particular a branch called category theory.

After graduating top of his class from the California Institute of Technology, Caltech, in 1983, he moved to the United Kingdom where he studied at the University of Cambridge.

There he met and fell in love with his partner, Australian musicologist Matthew Noone.

In 1986, he moved to Australia on a student visa to join Mr Noone and complete his PhD at the Australian National University in Canberra.

On 10 December 1988, spear fishermen found Scott’s badly broken body on rocks about 60 metres (200 feet) below cliffs at Blue Fish Point in the upmarket Sydney suburb of Manly.

Police believed his body had been there for two days.

His clothes were found “neatly folded” about 10 metres from the cliff edge, a police report stated. Police also found Scott’s watch, bank card, student ID and other possessions nearby. His wallet was missing.

After receiving the heartbreaking news that his brother and best friend was dead, Steve travelled to Australia two days later to try to find out more about what had happened.

Accompanied by a New South Wales police officer, he visited the spot where his brother had died.

In a 2020 interview with Insider, Steve recalled the police officer asked him: “Did you know your brother was a homosexual?”

Steve, who had a Masters degree in Public Policy from Harvard University, told the news site that police seemed to think that his sexuality was a motive for suicide.

Scott had come out to his brother four years earlier, the pair discussing it in depth while working a summer job programming computers in Los Angeles in 1984.

Steve never bought the idea that his brother had taken his own life. He showed no signs of depression and was not a heavy drinker or drug user.

The day of his death, Scott was told that his PhD had been accepted, and he had likely been looking to celebrate.

Different scenarios plagued Steve’s thoughts: maybe his brother had slipped or been pushed, he told Australia’s public broadcaster ABC in 2013.

“I didn’t know why we lost Scott.”

When Mr Noone reportedly told police about a previous suicide attempt that Scott had made, that was enough for them to close the case.

Steve lobbied for detectives to check his brother’s phone records, search his home or interview friends and potential witnesses and retrace his steps on the night he died.

They refused, and his death was ruled a suicide, without ever considering another cause of death.

A brother’s quest for answers

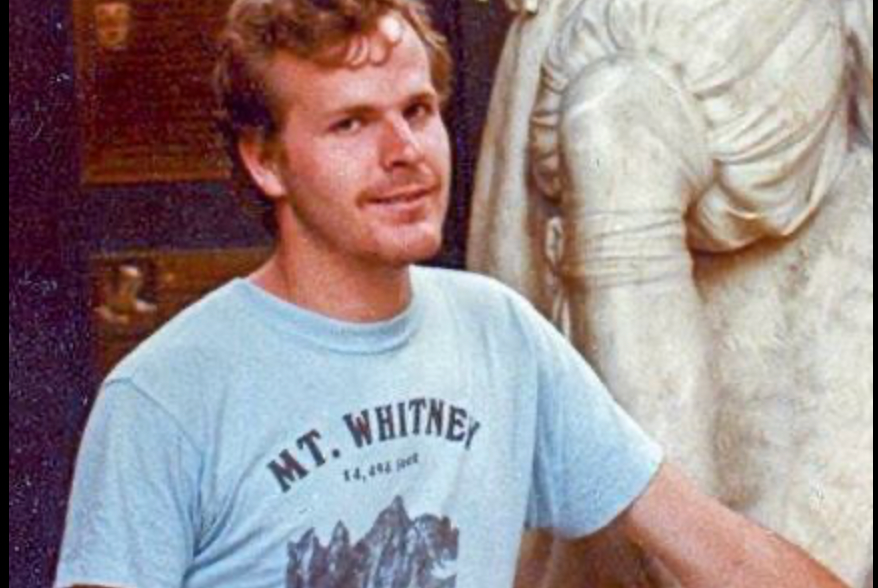

Haunted by his brother’s death, Steve decided to do whatever it took to find out what had really happened to Scott.

In the late 1980s, he was a married grad student with a young baby and next to no money.

Within a few years, the budding tech entrepreneur had developed an algorithm that compressed images enabling them to be sent much faster over phone lines.

In 1996, he sold his company to AOL for $100m.

He would later become a vice president at AOL’s software and technology development division, and has been described as a “central figure” in the early days of the internet.

The sudden wealth changed his life forever, Steve told ABC, so he decided to “roust some attention” on Scott’s case.

Prior to selling his company, Steve had already been making his own attempts to investigate the killing.

Steve learned that his brother would make the three-hour commute from Canberra to Sydney once a week to continue his doctorate work, staying with Mr Noone’s sister while there.

According to Insider, Steve then made contact with Senator Ted Kennedy through a Harvard connection to ask for his help.

The late senator reportedly contacted the US Ambassador to Australia to try to get them to encourage the New South Wales government to hold a coronial inquest into the death.

The plan worked, and the coroner agreed to hold the first of three inquests into Scott’s death in 1989.

At the hearing, Mr Noone testified that Scott had cheated on him six months before his death. He speculated that Scott may have done so again, and been racked with guilt.

Police officers told the hearing that they had not found any evidence that Blue Fish Point was a “gay beat”, local parlance for a spot where men would go to have sex.

The coroner would later rule that there was “no doubt” that Scott had taken his own life.

The official findings declared that being intelligent, shy and gay matched the profile of “the type of person who quite frequently does commit suicide”.

In a quirk of history, Ted Kennedy’s niece Caroline Kennedy was named the US ambassador to Australia in 2022.

A horrifying breakthrough

In 2005, and living back in Cambridge, Massachusetts, one day out of the blue Steve Johnson received a letter from his dead brother’s partner Mr Noone.

Steve told Insider the letter contained a handwritten note stapled to two articles that described recent inquests into the deaths of three young men who had been killed near cliffs in Sydney in the 1980s.

Their deaths, initially deemed inconclusive or accidents, had been reexamined and ruled as homicides.

The coroner described how packs of roving teenagers had been robbing and beating up men at known “gay beats” around Sydney.

The coroner criticised the earlier police investigations into the deaths as being “naive” and “disgraceful”. It determined that other murders may have been mistakenly classified as suicide or accidental by police.

In 2007, Steve hired former Newsweek investigative journalist Daniel Glick to investigate Scott’s death.

Mr Glick travelled to Sydney, and soon found the evidence that would challenge key aspects of the police’s version of events; that Blue Fish Point was in fact a place gay men frequented for sex, and that violent attacks had occurred there.

One local told Mr Glick that it was customary for men to fold their clothes neatly as a sign they were interested in having sex with a potential partner.

Steve and Mr Glick sent a report containing their key findings to police and the coroner.

The police showed no interest in reopening the case, and claimed the earlier suicide ruling meant their hands were tied.

‘It was a blood sport’

Steve’s investigative team had by this stage grown to include lawyers, journalists, a former police officer and activists in both the United States and Australia.

The group, dubbed Team Scott, continued to probe similar homophobic killings, court records, police documents and media clippings.

Their pressure campaign eventually led to a second inquest being ordered in 2012.

There, a coroner threw out the first ruling that Scott had died by suicide and returned an open ruling.

Then early in 2013, a documentary on the family’s fight to have the case reopened featured on the public broadcaster ABC’s flagship programme Australian Story.

The programme exposed how prisoners had been secretly taped boasting about having pushed gay men off cliffs. So-called “poofter-bashing” was apparently rife among violent gangs in Sydney at the time.

“It was a blood sport,” former Sydney detective Mark Page told the ABC.

Several months later, the Sydney Morning Herald published a bombshell report that as many as 80 men had been murdered in the late 1980s and early 90s, with 30 cases remaining unsolved.

Experts described it as an “epidemic of hate crime against gay men”.

New South Wales had only legalised homosexuality four years before Scott’s death. And the reports found that a wave of anti-gay hysteria, whipped up at the beginning of the Aids epidemic, meant many attacks were dismissed by police or went unreported.

Amid growing outrage at the homophobic attacks, New South Wales Police offered a $100,000 reward for information leading to his killers in 2013.

They announced the creation of a task force to investigate Scott’s murder. But within months, the investigation was wrapped up without identifying any suspects.

A third inquest

In a highly unusual move, a New South Wales coroner ordered a third inquest into Scott’s death in 2015.

The high-profile hearing, held in 2017, saw dozens of witnesses come forward to testify about how the hatred and violence towards the LGBTQ+ community had left many living in fear.

The then-NSW Coroner, Michael Barnes, found that Scott had fallen from the clifftop due to “actual or threatened violence” in a “gay-hate attack”.

Mr Barnes hit out at police for refusing to properly investigate the homicide.

In 2018, NSW Police increased the $100,000 reward for information leading to an arrest to $1m.

A few days after the announcement, Australia legalised same sex marriage.

Steve Johnson marched in the Sydney Mardi Gras that year in honour of his late brother.

Two years later, Steve doubled the reward by putting up $1m of his own money.

“With a reward of up to $2m on the table, I am hoping that Scott will finally get justice,” he told a press conference at the time. “Please, do it for Scott, do it for all gay men who were subject to hate crime, and now, do it for yourself.”

The enormous reward soon had members of Sydney’s criminal underworld spilling their secrets.

The arrest

In May 2020, New South Wales Police announced they had arrested 49-year-old Scott White for the cold case murder, news.com.au reported.

White’s former wife had tipped off authorities, and he had been caught on tape during an undercover police operation telling a niece: “I hit him. He hit me. He stumbled back. I went to grab him and he … just stumbled back.”

White, a father of six, reportedly told authorities he was gay, and that he had hidden his sexuality for decades from his family.

He claimed he had met Scott at a pub and gone to the cliff top together, before they got into a fight, and he shoved him over the edge. He was 18 at the time, and told authorities he was living on the streets and cognitively impaired.

In January last year, White entered a shock guilty plea to Scott’s murder, and was sentenced to 12 years seven months prison in November.

But the conviction and sentence were overturned on appeal, and White pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of manslaughter in February.

In a victim impact statement read to the court this week, Steve Johnson said he and wife Rosemary had “no sympathy” for the killer.

White’s decision to flee the scene without calling the police had prolonged the family’s grief and loss for decades, Steve said.

“He didn’t check on Scott. He didn’t call for help. He notified no one. He simply let Scott die,” Mr Johnson said.