An open letter to American broadcasters:

Whether serendipity or luck; we seem to be in an exceptional place. As the following article summarizes, it seems that we have the only combination of assets and technologies that make for effective Emergency Mass Communications. There are no practical alternatives.

With NVISA and FEMA in the lab, and what we hear from several milieus about the interest and willingness to invest in public safety, we are at a tipping point.

Acting as if our goal is to return TV to its bygone role as primary alerting and informing appliance is not helping. Smartphones dominate and “mobile first” is a respectable adoption strategy.

Everything good and bad with emergency communications occurs at the user interface. No one is happy with the current brain-dead, inconsistently alerting everyone everywhere, test it until no one listens state of affairs.

Sure, with 3.0 we have vastly better distribution and IP support, and presently broadcast news is uniquely the highpoint of electronic mass communications in crisis—but none of that matters without a national, universal, quality app and first-rate user experience.

It’s time to ask Congress/FEMA/FCC… the people who represent and protect us from invasion to tornadoes… to build what saves lives and property with our 3.0/broadcast assets. Intentionally or accidentally, broadcasters have already done their part. We have coverage and a protocol begging to be used.

The field piece of development is probably best done in the "Switzerland" of PBS/CPB. The lab should be FEMA’s. The broadcaster’s role going forward is to make sure this works with and enhances our news and our other assets.

Or maybe there is a better path?

Fred Baumgartner

This article originally appeared in The Spectrum Monitor and is the third in a series about NextGen Broadcasting:

Radio and public safety have always and forever been bound together. The lives radio has saved and the reduction in human suffering is colossal. The Spectrum Monitor (TSM) readers, especially first responders, know this in ways others do not.

Mass communications during an emergency has been broadcasting’s highest calling. For the most part, outside of weekly (or more often) testing of the Emergency Alert System (EAS), broadcast isn’t about emergencies—until it is. A major fire, hurricane, earthquake, tsunami, eruption, industrial accident, etc., does tend to completely consume broadcast media’s attention when it occurs.

Historically, both amateur radio and broadcast justify their spectrum grants with the public role they play when things go badly. The FCC takes this very seriously, issuing more notices of violation and fines for EAS than any other infraction.

When EAS was launched in 1997, we were just learning that simply ringing the alarm bell was not enough, and frequently unintentionally deadly. Our world, threats and especially our behaviors have changed since then."

In 1990, AM radio was king, the World Wide Web was born, a radio telephone call needed an operator to assist, local TV news was an hour a day, and NOAA weather radio (NWR) was sparse. When EAS was launched in 1997, we were just learning that simply ringing the alarm bell was not enough, and frequently unintentionally deadly. Our world, threats and especially our behaviors have changed since then.

The Digital Era

Smartphones... Emergency Mass Communications (EMC) is smartphones. When people evacuate, they do not take their TVs with them. Only a very few scramble for their wind-up AM radio. People in danger take their purses/wallets and… phones.

The singular and growing dependance on smartphones for most human-to-human and human-to-machine interactions is fact.

Humans over the age of five have their smartphones with them at all times. If you need your phone to start your car, park, open a hotel room door, order a hamburger, shop, or your location is being tracked by friends, family and advertisers, you know the disconnected, helpless, empty feeling of having misplaced or discharged your phone.

There is some investigation that suggests that smartphone dependency has the unintended consequence of increasing milling time. AEA/AEI on the other hand, directly ties critical information to the alert, thus eliminating search time and one would think reduce milling saving lives.

Natural Hazards Center Director Dennis Mileti (1945-2021) defined and studied “milling” as EAS was being developed. It is human nature for people to want to validate and spread the word of an emergency following an alert. Milling wastes valuable time and is often fatal.

It’s not all bad; spreading the word quickly is probably why survival rates are highest in tight/dense communities. Milling ends, and survival activities begin, when the crisis “becomes real,” to the participants. In a world of two-minute emergencies, there is no time to search or text, just time to act.

WEA predates the smart in smartphone. About five years into WEA, several emergency alerting apps made bids to intelligently fill the information gap. FEMA, the Red Cross, some schools, companies, and many local emergency management offices, and much of social media, offer many apps that residents can subscribe to… so many that there are posts and sites dedicated to advising which emergency apps and how many anyone should have on their phone. This fragmented EMC delivery.

By their nature, these apps address pieces of EMC, not the whole of EMC. The apps that focus on a few threats, where there is some intelligence (usually in the form of a local emergency management office or weather service) work well for their sphere of emergencies. The local or county emergency management office that invested in an app to deal with wildfires and has diligently marketed their app to citizens with the time and patience to download and the skills to configure the apps and maintain them, does well in their narrow circumstance.

Social media that scrape other sources for the grist that they warp into the attention-grabbing notifications that fuel and package EMC in click bait, might be notably delayed, unreliable, and soaked in crowd sourced misinformation… but they do work.

Bottom line? The state of EMC is a fragmented mix of the ancient and many emerging apps.

Missing Platform

It seems logical that that EMC should use every distribution platform it can. Radio, TV, Wireless, and social media (for better or worse) are ubiquitous. Signage and sirens (the ones with voice message speakers being most useful). However, streaming and satellite don’t help and cable support ranges from nonexistent to rather mature and well developed.

Arguably, smartphone dependence is so domineering that no other platform is required. As our dependence on smartphones continues to increase, soon enough the people reached by broadcast radio, etc., will become insignificant. But, if life is precious, and not everyone has their smartphone on their person, and wireless isn’t 100% reliable, it makes sense to alert on all platforms simultaneously… if for no other reason than to alert people to check their phones.

In addition to smartphones, NextGen Broadcast’s AEA/AEI (Advanced Emergency Alerting and Advanced Emergency Informing) is a good fit for cable, satellite, and internet.

Smart is Good

Some think that technology constantly pushes intelligence to the edge. Nowhere does this make more sense than in EMC. In EAS, and WEA, the radio, TV or device is dumb. It simply makes noise or displays the messages that are broadcast to it and every other receiver. In EAS, there is “where, what, when” information encoded in the FSK signaling we hear at the start of every alert.

This information allows EAS decoding receivers—a small brain is required—to activate when wanted. Most people might own an automatic NWS radio, but home EAS receivers are rare. The only people who directly receive an EAS activation are those watching or listening to a participating station where everyone gets everything because unlike AEA/AEI, EAS supersedes programming.

This forces the broadcast station into a “Sophie’s choice” situation as to what alerts are passed on. Is a tornado on the edge of the coverage area worth interrupting the Dallas Cowboys game? WEA is somewhat better, but the practical installations are still challenged to effectively target EMC. Occasionally waking to a 2 AM Amber alert for an adjacent state is where the state of WEA is after 10-years.

For EMC, a smart, location aware device that is always with us is a godsend. The smartphone has already displaced weather radios… along with cameras, watches, cash…

Smartphones have an amazing user interface with incredible flexibility and full bidirectional connection. TV remotes are inflexible molded plastic devices with a few or many molded buttons."

Want the same functions on a TV? There are only man-made barriers to this. Developing AEA/AEI on smartphones and gateways is fairly straightforward. These are well known mature and stable environments. Porting AEA/AEI to TVs is fairly easy for those TVs that have the memory, processing power, hooks, and storage to support it. Developing on multiple TVs from multiple manufacturers? … no one has that much money or patience.

Smartphones have an amazing user interface with incredible flexibility and full bidirectional connection. TV remotes are inflexible molded plastic devices with a few or many molded buttons. The best you can say about TV remotes is that navigating information is ugly. Some TVs use smartphones as a remote control (so called “second screen”). In this case, the TV becomes superfluous.

Assuming the code isn’t written with the same process that gave us healthcare.gov and is more like the low friction apps you find while online shopping (and there is adequate intelligence behind it) AEA/AEI solves all the problems we’ve substantiated since EAS was adopted.

First and foremost, AEA/AEI stops over-testing, over-alerting and mistargeting. Second is the availability of critical follow-on information. Having to search on an overloaded network for life and death information kills people. Language and disability access are no longer obstacles.

Bottom line? EMC is about smartphones. With a smart, well-designed, self-configuring, pre-installed app—AEA/AEI resolves the human behavior issues and user limitations—even the ones we inadvertently created.

UHF High Power

Smartphones on the wireless network have one serious, fatal, but resolvable limitation. In any medium to major crisis, the wireless network collapses.

While broadcast supports an infinite number of simultaneous users, common carrier wireless cannot support the flood of individual demands for information typical in an emergency. The capacity required does not exist. Intuitively, one would think that when the network chokes, the milling time increases dramatically and of course the lost information would have often been lifesaving.

Wireless requires multiple towers with often single-thread interconnect. This wireless architecture is far more fragile than broadcast which tends to be hardened, staffed and secured with backup power and everything else. When a wireless carrier or a tower fails, the people it serves are disconnected. When a high-power UHF broadcaster fails… the receiver simply retunes to the next strongest signal of many.

UHF is vital. UHF is necessary for building penetration and its big service area. It also needs to be built into the smartphone. Qualcomm put UHF TV into cellphones a decade ago, but no one has been able to do acceptable AM or FM reception. TSM readers know well the laws of physics and the inferiority of VHF and MW transmission in an urban or indoor environment.

In an emergency, you want to “carpet bomb” the population with a multitude of resilient high power RF. Wireless is extremely useful as events evolve, but EMC distribution shouldn’t rely on a low power, countless single-points-of-failure system that can’t survive a “scraped earth event.”

Further, the complex and exposed wireless network is vulnerable to cyber-attack and instabilities. Consider that AT&T, including Firstnet (the wireless service that AT&T contracts to independently serve first responders) failed nationally on Feb. 22, 2024 for hours. In July 2022, KDDI in Japan and it’s 39 million customers experienced, “…the biggest glitch in our history,” according to KDDI chief Makoto Takahashi, taking the entire system down for two full days. Rogers Canada has had multiple outages over the last three years impacting all of its Canadian customers.

And it’s not just wireless carriers. CenturyLink took three states of their internet customers “off the air” pre-Covid.

The unfailing and simple architecture of broadcast makes it much less likely to fail or fall victim to cyberattack. There has never ever been a time or event where more than one broadcast signal didn’t survive.

Intelligence

EMC is only as good as the information disseminated.

“Rich media,” beyond simple text, audio and video, is valuable. Searchable data, maps and visuals are very useful, expected, and rare. Emergency management organizations generally have neither the staff, equipment, nor expertise to prepare much more than simple text alerts.

TV news organizations are the American machine that aggregates information from all of the stakeholders, federal, state, and local governments, power companies, utilities, first responders, and the scene itself. Broadcast news can put cameras on the ground and in the air and put authorities in front of a microphone. Nothing new here. Broadcasters routinely forgo advertising revenues to cover major news of emergencies. However, legacy alerting is at best loosely attached to news.

Indispensably, broadcast news has the relationships to validate information.

NextGen AEA/AEI

Conelrad, EBS, EAS, WEA, sirens, signage, are or were all alerting systems under the control of broadcasters and to some degree emergency management, that could interrupt programming so that sometimes on-air talent or automated weather service speech synthesis can speak to the situation.

AEA/AEI directly connects all of emergency management to a user’s smartphone where the decisions of what to alert for and in what manner are made under the user’s control. AEA/AEI can share information in the manner that we are used to, without pre-NextGen broadcasting’s analog era limitations.

NextGen AEA/AEI smartphones (and other equipped devices like TVs) periodically check for AEA/AEI messages in addition to alerts via native WEA. For the OTA part, there is a balance between battery life and urgency. When a pair of bits in the ATSC 3.0 bootstrap (the lowest most secure data path) indicate that there is a message, the smartphone grabs it and runs it through filters.

The filter asks if this affects my location and if this is a situation where people should be notified or awakened. An Amber alert might wait until people wake up. An F-5 tornado in the neighborhood demands immediate attention.

No television station has to decide whether to interrupt programming, because AEA/AEI unlike EAS… doesn’t interrupt programming. On a TV, the video squeezes back, and there are three loud “attention” beeps with a text crawl. A viewer can dismiss, dig deeper… or grab the smartphone, which is doing the same things, and run for cover.

Every AEA alert is on every transmitter nearly simultaneously and goes to every phone without delay. Following the “in emergencies, all delivery methods are used” guidance, the internet and wireless are also useful paths. Ideally, the phone sees the same message from many places—and filters out the redundancies.

Where are We?

Both EAS and WEA have devolved into systems that neither broadcasters nor wireless providers have a positive incentive to maintain or improve. The public and emergency community complain about both. The last time we heard anything about EAS, broadcasters through the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) got Congress to force car manufacturers to continue support of AM radios, claiming that AM/EAS plays a critical role.

The reality is somewhat nuanced.

Today, “full service” radio stations are almost always AM/FM or FM only; only larger metropolitan areas support the necessary full-service station. While radio news operations have declined, TV and digital news has boomed. Radio on the dashboard is far more difficult and distracting to tune than the days of five buttons and a tuning knob. When you see “tune to 1610” traveler information signs while driving a rental car, you are unlikely to figure out how to listen safely without first pulling over.

My own experience is that I have not received a useful emergency message via my AM radio in many years. On the other hand, my cellphone has warned me of bad weather and with the help of the smartphone, I have navigated around hail, etc. at least a few times each year. AM radio used to do that, but not anymore—which is OK because the smartphone does this so much better—WEA messages are even displayed on my dashboard via the car/phone handsfree Bluetooth link.

As you might expect, most of broadcaster’s activities surround reducing their investment in EAS (including NAB and largely iHeart’s move to virtualize EAS to avoid replacing hardware), news and other staff intensive programming.

EAS does little good for broadcast news, sometimes interrupting live tornado coverage with a less informed and often delayed NWS issued tornado warning. Broadcasters, especially the ones that embrace the vision of a broadcast digital news operation that is ubiquitous, interactive, and low friction, do have motivation to develop AEA/AEI.

It expands the news department’s reach and gives them a lower friction platform for disseminating information from the trivial to the ultra-critical. AEA/AEI builds on and can deepen a station’s relationship with its viewers. Unfortunately, EAS drives viewers and listeners away with constant false alarms, tests and untargeted use.

So Where is the NextGen EMC Application?

The broadcast app that supports AEA/AEI has yet to be written. There have been several starts, each of which stalled at the mockup stage. We’ve seen what it might look like, but not how it works.

Unfortunately, vaporware is impossible to demonstrate and very difficult to describe outside of abstractions. If you want to show emergency management, broadcasters, regulators, or the general population AEA/AEI, we will have to build it.

Within ATSC is the “I-team.” The only implementation effort under the ATSC umbrella is to develop AEA/AEI. In the I-team’s long history, they have only had access to BAs (aka "Broadcast Apps" installed on the smartphone by the broadcasters) that function on an EAS level, meaning that they have yet to experience a BA that does the advanced filtering functions, or supports rich media information dissemination. ATSC and their I-team have nothing close to a deployable AEA/AEI app.

As this is written, NVISA and FEMA have set up a NextGen Emergency Mass Communications laboratory in Maryland. This is all very good. For now, without an AEA/AEI app and mobile devices, all that can be done here is to play with TVs and basic prototype BAs able to do little more than alarm. When we do have a BA, this is the place to test it and make it work before it is released into the real world. FEMA has a test version of IPAWs very useful for this.

3.0 Enabled Smartphones

NextGen AEA/AEI depends on a smartphone running an AEA/AEI app that receives information via the wireless network when available, and information embedded in NextGen UHF Broadcast high power, big tower transmission when wireless access becomes impossible.

India seems to be the place where NextGen smartphones are taking off. Not so much in America.

Next Step

Without a BA and 3.0 chips in smartphones, we do not have resilient, intelligent EMC.

For broadcasters, what revenue potential there is in funding the BA is maybe from licensing what has never been licensed before (EAS is public domain) and/or betting that broadcast news can someday benefit from the AEA/AEI platform. It is also uncomfortable for broadcasters to depend on a competitor for a critical piece of broadcast architecture.

There have been rumors of various players crafting a proprietary BA, usually more focused on monetization issues than AEA/AEI. So far, there is no AEA/AEI progress. There have been two efforts to cooperatively advance this endeavor within the industry.

NAB Pilot’s effort ended quietly, apparently lacking broadcaster support and some member opposition to NAB supplying a universal “free” app. Later, NVISA invited broadcasters and vendors to cooperatively do such. NVISA (NextGen Video Information Systems Alliance) received no response from the major players.

As mentioned above, ATSC’s I-team dedicated to AEA/AEI implementation has no resources beyond the power of the regularly scheduled meeting. Also, ATSC is a standards organization, so as one would expect, implementation—as much as it is needed—is well outside ATSC’s tradition and resources.

AEA/AEI serves the public good. As a nation, we do invest in our security and safety. In 2006, Congress put $106 million into the Warning, Alert, and Response Network (WARN) Act. This funded Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) as well as other upgrades to EMC. More recently, congress has designated funds to upgrade EMC, in several different “buckets.” While AEA/AEI is likely the most important thing we should do, a lot more expensive and less important things seem to be on current agenda.

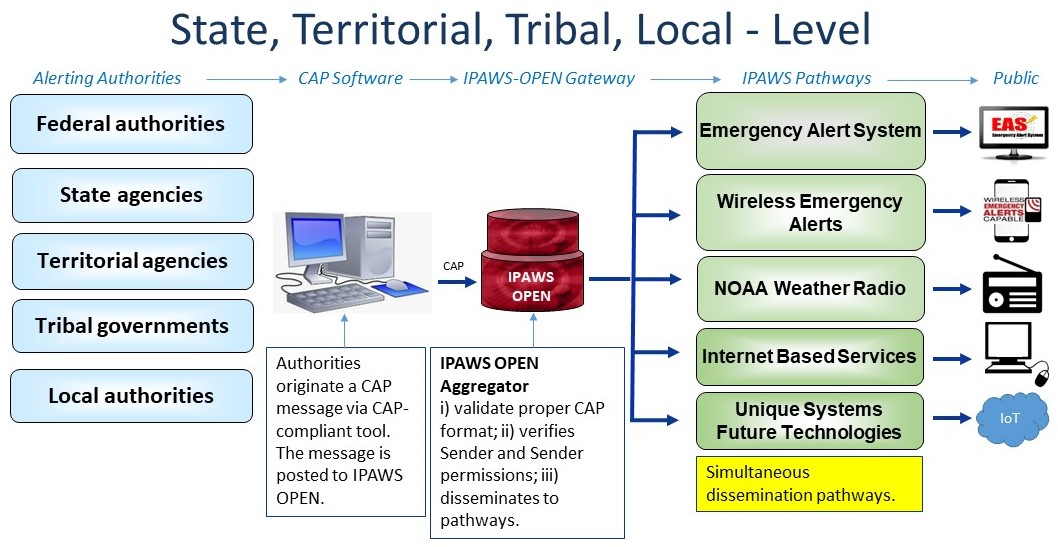

This is also close to the charter of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, who with PBS, have a history of nurturing similar technologies such as closed caption in the early 1970s. That lead to the passage of the Television Decoder Circuitry Act of 1990. PBS has been active in the EMC field with WARN, a system that backs up IPAWS (Integrated Public Alert & Warning System) internet delivery. There have been several NextGen proof-of-concept demos within public broadcasting for the benefit of first responders and EMC.

It is also better that there be just one AEA/AEI BA that operates in a manner where everyone everywhere can easily understand it and navigate. Competing BAs can create unnecessary friction. This is software and NextGen is “extensible,” meaning that the system can be updated and fine-tuned over time.

The bottom line is, that if we want reliable and powerful Emergency Mass Communications, FEMA and the FCC, if not congress, have to say so.