A tremendous cosmic explosion 2.4 billion light years away temporarily changed the electric field in Earth’s ionosphere (the electrically-charged upper layer of our atmosphere that helps shield life on Earth from dangerous ultraviolet and other radiation from space).

The results shed some light on how our planet’s protective layers of plasma interact with radiation from faraway events in space — and how we can use the ionosphere to detect and study gamma ray bursts.

University of Aquila astronomer Mirko Piersanti and colleagues published their work in the journal Nature Communications.

Earth’s Energy Shield Takes a Hit

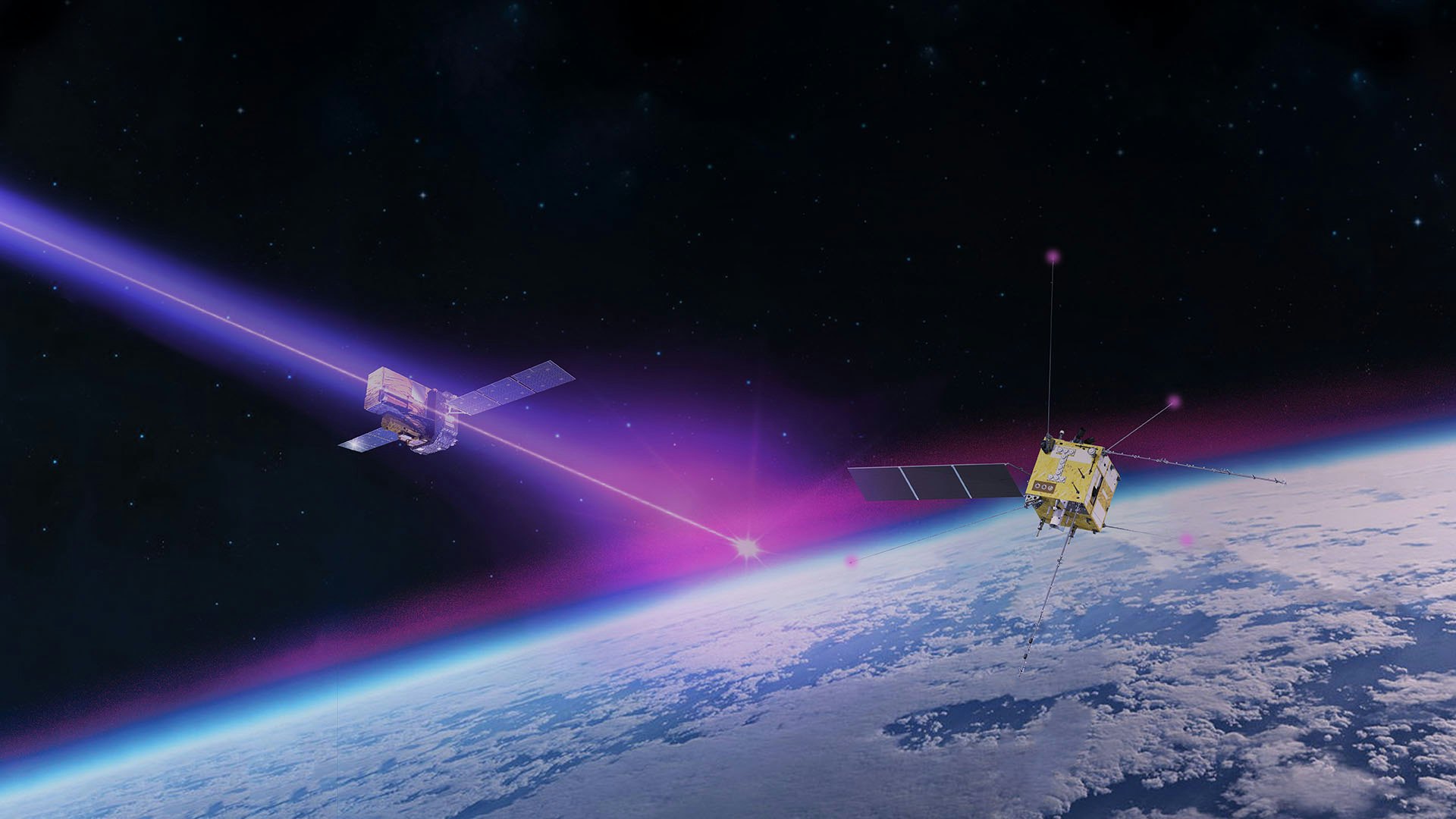

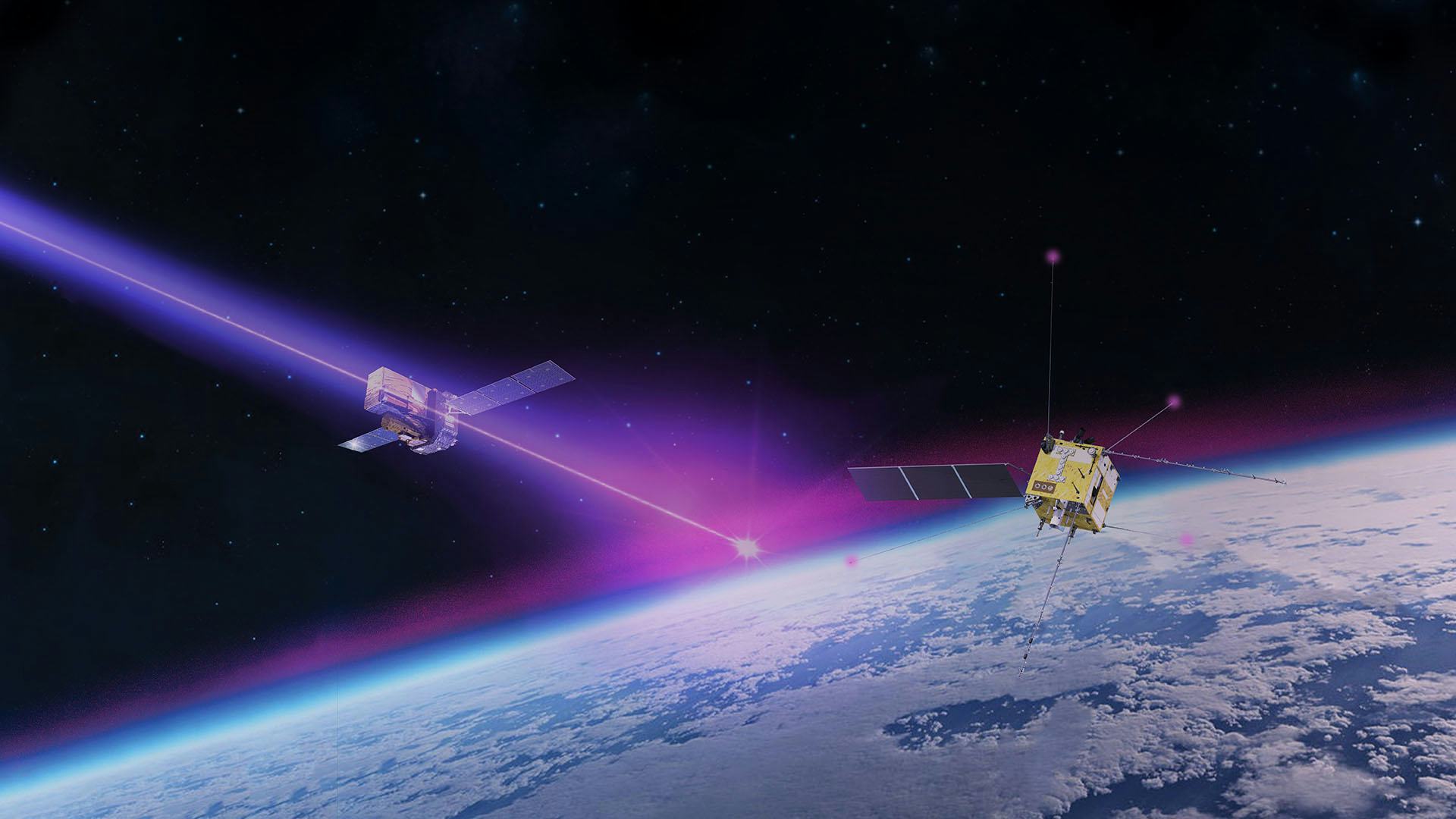

In October 2022, a galaxy 2.4 billion light years away suddenly flared with the brightest gamma ray burst astronomers had ever seen. Piersanti and colleagues used radio transmitters and satellites to measure what happened when the gamma rays struck the upper layers of Earth’s ionosphere. It turned out that the high-energy radiation caused more of the gas than usual to ionize, or take on a different electrical charge, which changed the electrical field of the whole upper ionosphere.

Earth’s ionosphere is actually several layers of electrically charged gas, called plasma, floating at different altitudes in the upper atmosphere. Those layers help block harmful ultraviolet and other radiation, making our planet livable. They’re also handy for radio operators, who can bounce radio signals off the plasma layers to reach receivers on the far side of the horizon.

That means scientists can measure properties of the ionosphere, like its density and its electrical charge, based on how it reflects radio waves back to Earth or to satellites in orbit. And in October 2022, at the same time that astronomers detected a tremendously bright gamma ray burst in a distant galaxy, other scientists noticed that the upper ionosphere’s electrical field was seriously perturbed.

Studies published earlier this year already measured similar effects in the lower layers of the ionosphere, but scientists hadn’t managed to measure how a gamma ray burst impacted the upper layers until now. Piersanti and colleagues say the work gives us a more complete picture of how our planet’s protective shield reacts not only to outbursts of plasma and energy from our familiar Sun, but to higher-energy radiation from much bigger events far off in space. Studying the ionosphere may even be another way for astronomers to detect and study gamma ray bursts in the future.

Don’t Panic (at Least Not About GRBs)

Gamma ray bursts are the most energetic explosions in the universe, and they seem to come in two varieties. The short ones last just a few seconds, and those seem to be what happens when two neutron stars – the extremely magnetic, super dense cores of dead stars – collide. Longer ones, like the seven-minute-long burst in October 2022, happen when massive stars collapse and form black holes.

Every gamma ray burst astronomers have ever recorded — and there have been a lot of them, since satellites like NASA’s Swift and Fermi space telescopes record at least one every day for the last ten years – has come from well outside our galaxy. And that’s a good thing, because a gamma ray burst here in the Milky Way could wipe out all life on Earth, if its beams happened to be pointed in our direction. At that range, the gamma rays would strip away our ionosphere and irradiate the surface of our vulnerable little planet.

Don’t panic: the chances of that happening are extremely rare. First, a massive star in our galaxy would have to collapse into a black hole, and the energetic beams of gamma rays and x-rays that blast outward during a gamma ray burst would have to actually be pointed at Earth. The odds of that are pretty slight.

How slight, exactly? The October 22 gamma ray burst was the brightest and the closest one astronomers have ever seen — and it was 2.4 billion light years away. According to NASA, that was a one in ten thousand year event.

In fact, even though astronomers record a gamma ray burst from somewhere in the universe at least every day, only a handful have had measurable effects on Earth’s ionosphere at all. And now we understand those effects a little better.