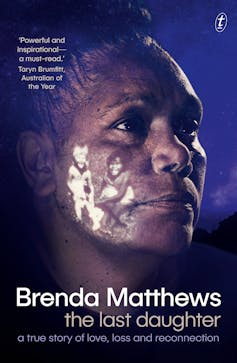

The woman’s face is in profile, her eyes looking into the distance – or the past, or the future. This is a quiet woman, a thoughtful one; possibly one who also carries sadness in her soul. This woman’s face is natural, a face with features as familiar as my own – a strong brow, deep-set and dark eyes, and full unvarnished lips set with an appealing cupid’s bow. Her hair is swept up, the background is purple-blue – evocative of a beautiful night sky.

I don’t know why it takes me the full read of her book before I see the photograph of two children superimposed on her right cheek: one child white-skinned with blonde hair, the other dark-skinned with dark hair. It’s a happy photo, as natural as they come.

Before this photograph of the children came into focus, my mind’s eye assumed it was white ochre, placed ready for a ceremony of some sort. The book, The Last Daughter, recounts the woman’s life to a certain midlife point. It ends with insight into the making of a documentary feature film, released this week.

Review: The Last Daughter – Brenda Matthews (Text Publishing)

The book is a ceremony of sorts: a bringing together of the woman’s story of families, Country, love, separation, heartache. And at its centre, a truth-seeking quest to right the wrongs perpetrated by a government hell-bent on doing “as they saw fit” when it came to Aboriginal peoples, with little regard for the consequences. The woman is Brenda Matthews, née Simon, born 1970.

This birth year renders her officially ineligible for being recognised as part of the Stolen Generations: the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Act was repealed and the Aboriginal Welfare Board abolished in 1969. She was removed from her family four years later, in 1973.

Stolen, again and again

Brenda was one of eight children, seven of whom were heartbreakingly removed from and then haphazardly returned to their parents, Brenda Simon née Hammond and Gary Simon. Brenda was the last to be returned home: after five years. She was two years old when she was taken and seven when she was returned.

She describes her mother’s memory of doing the household chores with a friend one day, “a few days” after she took her sick child Karla to the local hospital. “A car pulled up outside and two Welfare Department officers got out.” Her friend asked if they’d come to inspect the house. “Welfare officers were often inspecting Aboriginal homes to check if they were clean, which was often an excuse and a precursor to taking the children.”

But they had arrived “to take the kids”, on mysterious charges of neglect. Local knowledge about collusion between the local hospital matron and the Welfare Department does not escape mention.

After three months in a home, Brenda was fostered by a White family, who had a daughter of a similar age. “She is my younger sister and I love her,” recalls Brenda in the book. They believed they had adopted Brenda, and that a single mother had given her up. Five years later, she was returned home, with almost no transition. “I was ripped from both these families,” she writes later in the book, looking back.

This memoir reveals Brenda reconciling with this past, 40 years later, bringing her “Black family” and her “White family” together. The trauma impacts of these separations can be read through this life story, not least when 18-year-old Brenda tells no one she is pregnant and ends up giving birth alone in her bedroom:

I think deep down inside, I’m scared of this baby being taken from me because I was taken away from my Mum and Dad. I don’t want history to repeat itself.

Baby Keisha enjoys unbroken bonds with her parents and both extended families. Later, she is joined by four brothers, then by four more siblings, through her mother’s marriage to stepfather Mark. By the end of this book, Keisha has two children of her own – who become central to Brenda’s commitment to her story, her families, and a future free from cruel intervention.

History as told in The Last Daughter – family separation and its resulting trauma – does not repeat for future generations. But its effects continue to find sad reverberation in the life experiences of Brenda, her parents and her siblings.

Before her own children were “shoved” into a government car, Brenda’s mum had lived in fear of exactly this – as a teenager, she witnessed a cousin taken from her Aunty Greta.

Thinking about these removals under false charges, Brenda wonders what other lies are recorded as fact in government files about other family members, particularly after uncovering – with the help of historian and Wiradjuri woman Kim Burke – that Brenda’s maternal grandmother and great-grandmother were also stolen.

What chance did we have? Stolen, again and again and again. This is one family heirloom that didn’t need passing down, and the only blessing is that Mum was not stolen.

‘This is real history’

Members of Brenda’s White family are also left affected by the brutality of government policy: they provided a home to a little girl they fell in love with and whom their biological children considered a sibling. The youngest of this family, Brenda and Rebecca, are the girls on the cover image. And while there was nothing natural about how they became siblings, the love and joy between them is impossible to ignore.

Brenda tells the story of reconnecting with her White family. The young ones – Mark’s daughters – prove pivotal in this; their internet sleuthing and Facebook friend requests prove the bridge to the reconnection. Kiara gets a notification ping while in class and her teacher “reminds her that she is in a history lesson”. Kiara replies, “this is real history”, as she walks out. Later, she is able to confirm with Brenda that her White mum wants to see her.

Brenda’s ability, with the help of her husband Mark, to blend a new family across culture and history – despite the intergenerational trauma – is another feature of this life story.

There are many moments in The Last Daughter that make a reader pause and reflect on the power of love and belonging. When Brenda and her mum uncover, with the help of historian Kim Burke, that they are Wiradjuri rather than Wailwan, it’s a difficult adjustment to make. But after much work, Brenda is now comfortable saying she is a proud Wiradjuri woman.

“I can see her wrestling with this new information and who she thought she was all along,” writes Brenda of watching her mother in their moment of discovery. “This is common for a lot of Indigenous people who were taken from their Country and placed somewhere else,” Kim tells them.

Reconnecting with Country and culture is part of Brenda’s story. She learns the ancient art of weaving and works with Mark running camps on Country, in northern New South Wales and South East Queensland (with the endorsement of influential Indigenous figure Kyle Slabb from Fingal). This informs and deepens Brenda’s strength of Aboriginality.

It is at one of these camps where Mark encourages Brenda to tell her story:

I walk up to the line that Mark has drawn in the sand where he’d like me to stand, and I rub it out with my foot, drawing a new one a bit further back where I’m more comfortable. I am about to tell my story to strangers for the first time in my life. I’m fiddling with my hands and fingers. I take a deep breath and as the words start coming out of my mouth, memories come flooding back, and tears roll down my cheeks.

Read more: Friday essay: we are the voice – why we need more Indigenous editors

Countering lies and bearing witness

Finding voice, being heard and validated, is part of the human condition. The Last Daughter expresses it so well.

Brenda tells her story simply, with nothing exaggerated for effect; known facts, recalled memory and renewed encounters are drawn together in spare, first-person prose. A memoir born from journal entries reproduced as exposition throughout, The Last Daughter is inspired by Brenda’s need to know and share the truth.

She is motivated to counter lies about her parents, grandparents and great-grandparents – recorded as fact in government files. In just one example, the files record Brenda’s mother requesting a photograph and progress report on Brenda while she was with her White family; it says these were supplied, but Brenda’s mother never received anything. Even the date Brenda was returned to her family was incorrect.

Brenda’s motivation increases when she and her siblings are excluded from formal recognition as being part of the Stolen Generations.

The letter leaves me feeling like a microcosm of this land. It has been declared terra nullius – empty land – despite my people living here. Now my emotions, my memories, my trauma don’t exist in the eyes of the government.

Brenda’s pursuit of truth is reflected in the difficult conversations she has with herself, and with so many others in her Black, White, own (and eventually blended) family.

I can’t fully imagine the courage, fear, heartache and dedication it took for Brenda to peel back the years and the layers to find truth for so many. The book is a project of love and reconnection.

Keeping everyone inside the warmth of that fire cannot have been easy. That fire and its warmth are offered with immense grace to readers – and now viewers – of Brenda’s story. It is up to us to step inside that embrace and bear witness.

The documentary feature film, The Last Daughter, will screen in cinemas Australia-wide from 15 June 2023.

Sandra Phillips receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.