Astronomers have developed a new way to trace the paths of potential “city-killer” comets years before they come close to the Earth.

The breakthrough technique, described in a yet-to-be peer-reviewed study, finds such space rocks by detecting the crumb-like trails they leave behind in their orbits as meteor showers.

Most long-period comets, or LPCs, which take over 200 years to complete one orbit around the Sun, remain undiscovered until they near the Earth.

Some of these comets that pass close to the Earth are classified as “potentially hazardous”.

LPCs may cause up to 6 per cent of all impacts on the Earth and those about the size of a skyscraper could destroy a major city.

But only a small number of LPCs that could pass very close to the Earth have been found.

Comets with even extremely long orbital periods of about 4000 years that pass by the Earth produce “crumb trails” that can be detected as meteor showers.

The trails form as heat from the sun vaporises the comet’s ice. The streams of rocks and dust ejected from the comet as a result may sprinkle down as meteor showers on the Earth when the planet passes through the debris trails.

Researchers can now analyse a meteor shower to locate its parent comet. They can find the rock’s speed and direction of travel from the properties of the meteor streak.

The upcoming Legacy Survey of Space and Time project at the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile may boost the detection of comets this way years before they pose a threat to the Earth, the researchers say.

To test the new technique, the researchers analysed 17 meteor showers whose parent LPCs were already known.

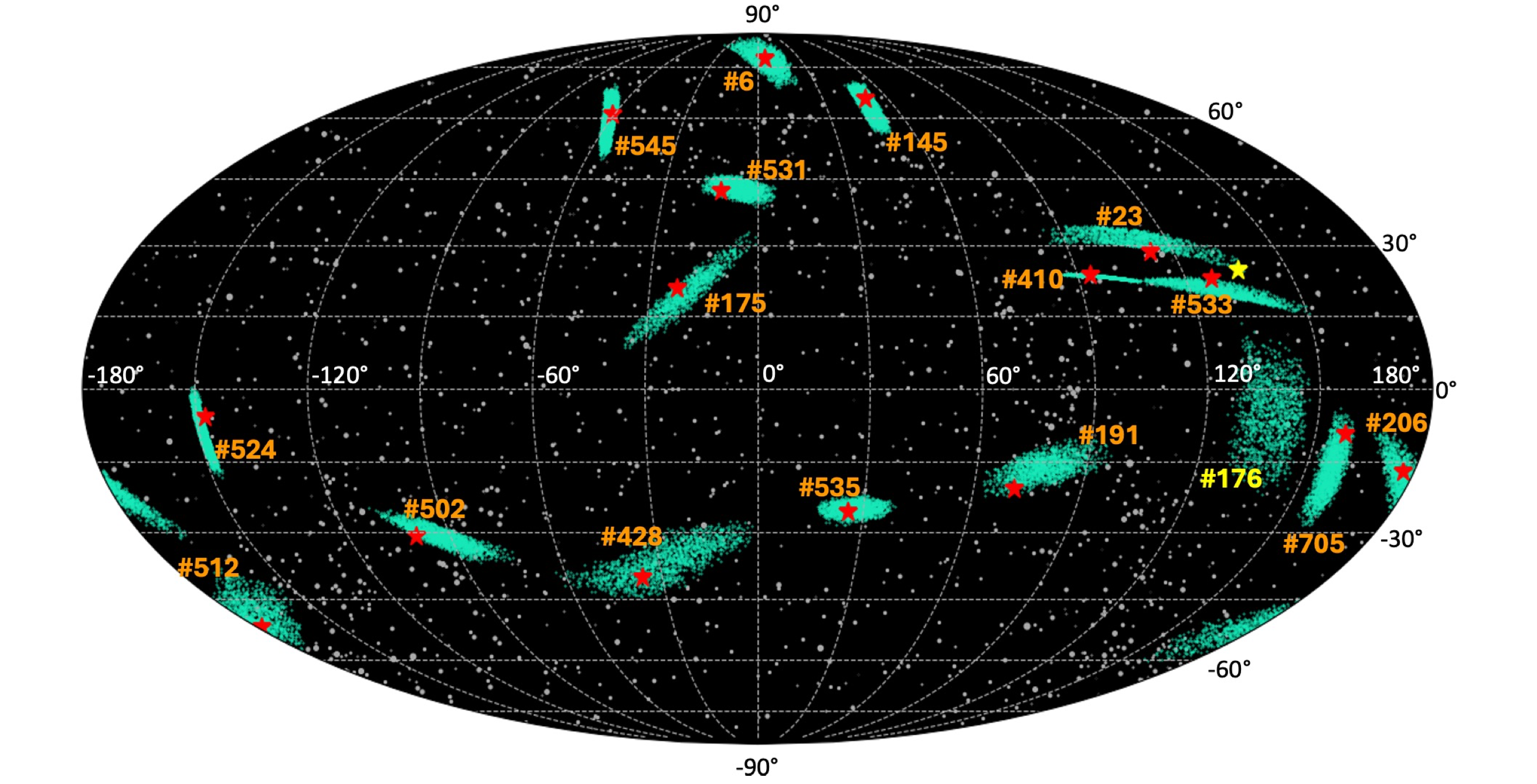

They assessed the properties of the meteor showers and created artificial models of their LPCs, one comet cluster for each meteor shower.

They placed these comet clusters virtually in space at distances which could be seen from the Rubin Observatory.

They compared the locations of the virtual comet clusters with the positions of the real comets to see how well they matched.

The astronomers found that the positions of the actual parent comets were largely within the clouds of the virtual projections.

“We find that the synthetic comets predict the on-sky location of the parent comets at the time of their discovery,” they said.

Analysing the properties of the comet particle streams can also help trace back and narrow down the area to look for their parent comets.

“The meteor shower informs which region of the sky the parent will be in as well as its speed and direction of motion,” the scientists said.

This could help identify comets that could potentially impact the Earth when they are billions of miles away, giving researchers enough time to track them and plan countermeasures.