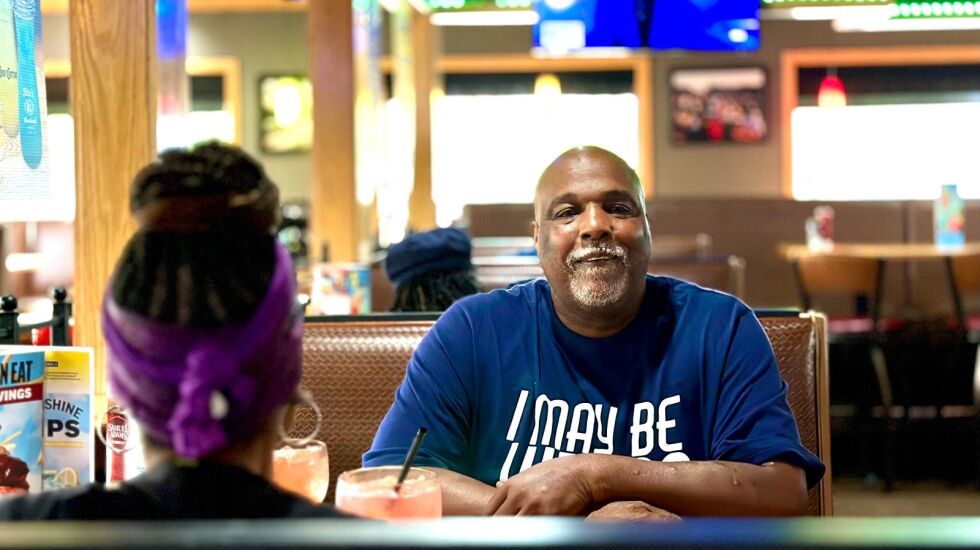

On a rainy day when his construction company calls off its workers, James Williams likes to go to the Applebee’s on Chicago’s Northwest Side and dine with his wife, Shawn.

Applebee’s has “decent deals, they have great prices, oh, and they have great drinks,” said Williams, 60, of Belmont Cragin.

He’s fond of the endless boneless chicken wings. He also likes the friendly service.

“They treat me the same as if I was a regular guy just walking off the street,” Williams said. “They have to accommodate the rich, the poor. They have decent everything, so this works for me.”

Williams is hinting at the wide appeal of his neighborhood Applebee’s, a characteristic that has an unintended effect: people from different economic backgrounds gathering under the same roof.

Applebee’s restaurants are among a handful of places in the United States where people from high-income and low-income neighborhoods encounter one another.

Chain restaurants represent places that have the potential to break class barriers, according to a new study titled ”Rubbing Shoulders,” co-authored by economist Maxim Massenkoff at the Naval Postgraduate School in California and sociologist Nathan Wilmers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Massenkoff said after reading Harvard economist Raj Chetty’s “Moving to Opportunity” study about segregation and its impact on children’s outcomes, he and Wilmers wondered, “Where in the world are we most likely to encounter someone different?”

Using large-scale cellphone data that tracks people’s movements throughout the day, Massenkoff and Wilmers found that in the U.S., “high-income and low-income groups are both isolated. When they do one of their typical outings, they’re a lot more likely to encounter someone else who is either rich or poor.”

According to the study, the places where people from high-income and low-income neighborhoods are least likely to mix are parks, churches, pharmacies and schools.

“One of the big reasons why is proximity … that’s going to explain a big chunk of the isolation that we see in the data,” Massenkoff said. He said people go to drugstores and attend school close to home, and most people live near others with similar socioeconomic status.

It came as a surprise to the researchers, then, to find that full-service, sit-down restaurant chains — with their expansive menus, reasonable prices and vinyl-booth seating — were among the few places where people from high-income neighborhoods came in contact with those from low-income neighborhoods.

The bottom 20% of neighborhoods, Massenkoff said, have a median household income of $37,000 and below. Neighborhoods at the top 20% have a minimum median income of $85,000 — with many residents in that neighborhood making more than that.

According to the study, among selected national chains, Olive Garden took the top spot for cross-class mixing, followed by Applebee’s and Chili’s Grill & Bar.

Massenkoff and Wilmers then connected their findings with data from a different study by Chetty and his team — about cross-class Facebook friendships.

“The places where you see a lot of cross-class friendships, you also see the kinds of chains where you see mixing under that roof,” Massenkoff said.

He added that chain restaurants appeal to a broad range of customers across generations with varying income levels and palates.

“These are restaurants which tend to offer pretty reasonable prices and a lot of consistency,” Massenkoff said. “And based on my experience, I think a lot of times, they might be the only game in town.”

Although the study is national, chain restaurants are ubiquitous and predictable: qualities Chicago-area residents appreciate.

Last week, West Lawn resident Valentin Rodriguez dined with his son at the nearby Olive Garden in southwest suburban Burbank, by Midway International Airport.

He was not surprised by the results of the “Rubbing Shoulders” study.

“Everyone likes Italian food,” Rodriguez said. But he offers a caveat. “There’s no chef here; you know it’s like microwave food, but … it’s consistent.”

Jennifer Hernandez, who had come with her family to celebrate her 20th birthday, said the restaurant is a versatile option.

“There’s something for every occasion,” she said. “You can come dressed up, you can come dressed down. You can come for special occasions.”

She said she has yet to befriend someone she met at Olive Garden, but “I wouldn’t be surprised if that happened.”

Applebee’s and Olive Garden did not respond to requests for comment on the study’s claims.

For Massenkoff, the study could provide a blueprint for those who are “excited about opportunities to mix across class lines.”

He adds: “It’s not saying that if you randomly plop an Olive Garden or an Applebee’s somewhere, that you’ll see a whole bunch of really beautiful new friendships blossom — but it’s consistent with that idea.”