Brazilian wandering spiders are aggressive spiders that belong to the genus Phoneutria, which means "murderess" in Greek.

These critters, also known as armed spiders or banana spiders, are some of the most venomous spiders on Earth. Their large mouthparts, or chelicerae, inflict painful bites loaded with neurotoxic venom that can be deadly to humans — especially children — although in most cases immediate medical care can prevent death with antivenom, according to a 2018 study in the journal Clinical Toxinology in Australia, Europe, and Americas.

Brazilian wandering spiders are frequently listed among the deadliest spiders in the world. They were named the world's deadliest spiders multiple times by Guinness World Records, although the current record-holder is the male Sydney funnel-web spider (Atrax robustus). But "classifying an animal as deadly is controversial," Jo-Anne Sewlal, an arachnologist at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago, previously told Live Science. Each bite is unique, and the damage it causes depends on the amount of venom injected, Sewlal said.

Classification/taxonomy

There are nine species of Brazilian wandering spider, all of which are nocturnal and can be found in Brazil. Some species also can be found throughout Central and South America, from Costa Rica to Argentina, according to a 2008 article in the journal American Entomologist. Study author Richard S. Vetter, a research associate in the department of entomology at the University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources, wrote that specimens of these powerful arachnids have been mistakenly exported to North America and Europe in banana shipments. However, Vetter noted, in many cases of cargo infestation, the spider in question is a harmless banana spider (genus Cupiennius) that is misidentified as a Phoneutria. The two types of spiders look similar.

The taxonomy of Brazilian wandering spiders, according to the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS), is:

Kingdom: Animalia

Subkingdom: Bilateria

Infrakingdom: Protostomia

Superphylum: Ecdysozoa

Phylum: Arthropoda

Subphylum: Chelicerata

Class: Arachnida

Order: Araneae

Family: Ctenidae

Genus: Phoneutria

Species:

- Phoneutria bahiensis

- Phoneutria boliviensis

- Phoneutria eickstedtae

- Phoneutria fera

- Phoneutria keyserlingi

- Phoneutria nigriventer

- Phoneutria pertyi

- Phoneutria reidyi

- Phoneutria depilata, according to a 2021 study published in the journal ZooKeys, which found that Phoneutria boliviensis actually included two separate species from different habitats.

Size & characteristics

Brazilian wandering spiders are large, with bodies reaching up to 2 inches (5 centimeters) and a leg span of up to 7 inches (18 cm), according to the Natural History Museum in Karlsruhe, Germany. The species vary in color, though all are hairy and mostly brown and gray, although some species have lightly colored spots on their abdomen. Many species have bands of black and yellow or white on the underside of the two front legs, according to the University of Florida.

Behavior

These arachnids "are called wandering spiders because they do not build webs but wander on the forest floor at night, actively hunting prey," Sewlal told Live Science in an interview conducted in 2014, before her death. They kill by both ambush and direct attack.

They spend most of their day hiding under logs or in crevices, and come out to hunt at night. They eat insects, other spiders and sometimes, small amphibians, reptiles and mice.

Research into one species of Brazilian wandering spider, Phoneutria boliviensis, revealed that these spiders eat a mix of arthropods and reptiles. DNA metabarcoding, a technique that examines the DNA and RNA in a sample, of the guts of 57 spiders identified 96 prey species, including flies, beetles, butterflies, moths, grasshoppers, locusts and crickets, according to research from the University of Tolima and the University of Ibagué in Colombia. Some of the female spiders also ate lizards and snakes.

While their bites are powerful and painful, "their bites are a means of self-defense and only done if they are provoked intentionally or by accident," Sewlal said.

When Brazilian wandering spiders feel threatened, they often assume a defensive position by standing on their hind legs and stretching out their front legs to expose their fangs, according to the 2018 study in Clinical Toxinology in Australia, Europe, and Americas. This posture is sometimes accompanied by side-to-side movements. The spiders can also jump distances up to 1.3 feet (40 cm).

Mating

In the Brazilian wandering spider, just as in most spider species, the female is larger than the male. Males approach females cautiously when attempting to mate, according to the biology department at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse. Males perform a dance to get females' attention, and males often fight each other over the female. The female can be picky, and she often turns down many males before choosing a mating partner. Once she does pick one, the male needs to watch out; females often attack the males once copulation is finished.

The female then can store the sperm in a separate chamber from the eggs until she is ready to fertilize them. She will lay up to 1,000 eggs at a time, which are kept safe in a spun-silk egg sac.

Brazilian wandering spiders typically live for one or two years.

Bites and venom

Brazilian wandering spiders' venom is a complex cocktail of toxins, proteins and peptides, according to the Natural History Museum in Karlsruhe, Germany. The venom affects ion channels and chemical receptors in victims' neuromuscular systems.

After a human is bitten by one of these spiders, they may experience initial symptoms such as severe burning pain at the site of the bite, sweating and goosebumps, Sewlal said. Within 30 minutes, symptoms become systemic and include high or low blood pressure, fast or a slow heart rate, nausea, abdominal cramping, hypothermia, vertigo, blurred vision, convulsions and excessive sweating associated with shock. People who are bitten by a Brazilian wandering spider should seek medical attention immediately.

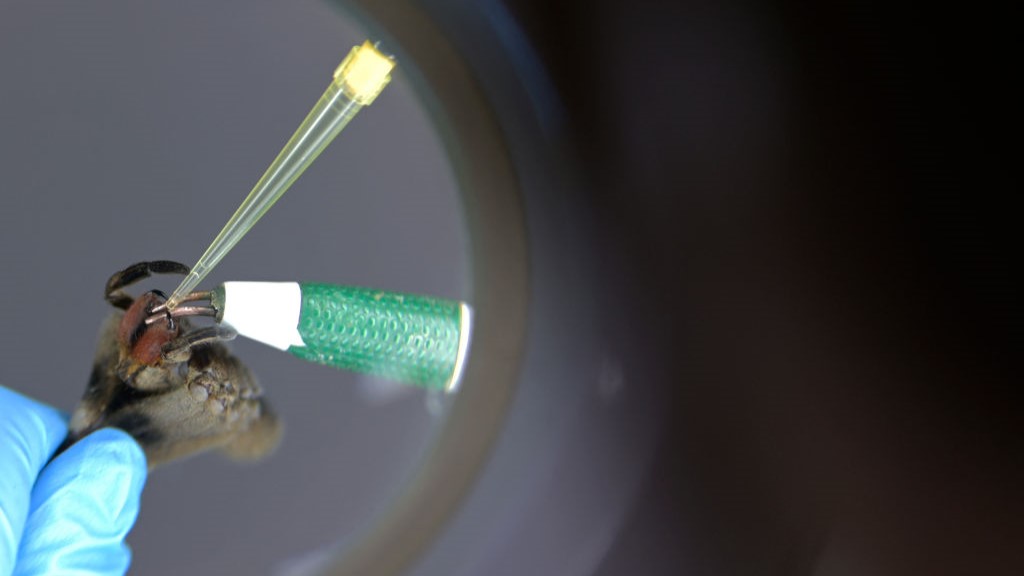

Their venom is perhaps most famous for triggering painful and long-lasting erections. For that reason, in a 2023 study, scientists reported that they were testing the venom in humans as a potential treatment for erectile dysfunction in those for whom Viagra didn't work.

However, these bites are rare, and envenomations, or exposure to these toxins from a spider bite, are usually mild, Vetter said. For instance, a 2000 study in the journal Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo found that only 2.3% of people with bites who came to a Brazilian hospital over a 13-year period were treated with antivenom. (The other bites did not contain enough venom to require it.) Most of the bites were from the species P. nigriventer and P. keyserlingi in eastern coastal Brazil. About 4,000 bites reportedly happen each year in Brazil, but only 0.5% of those cases are severe, according to the 2018 study. Meanwhile, 15 deaths have been attributed to Phoneutria in Brazil since 1903, the 2018 study reported.

"It is unlikely that the spider would inject all of its venom into you, as this venom is not only needed as a means of defense but to immobilize prey," Sewlal said. "So if it did inject all of its venom, it [would] have to wait until its body manufactured more before it could hunt." That would also leave the spider vulnerable to being attacked by predators.

Furthermore, Sewlal pointed out that venom production requires a lot of a spider's resources and time. "So if the spider were to attack frequently and use up all of its venom, it [would] be safe to assume that it has a ready food supply to replace the energy and resources used. This situation does not exist in the wild."

Additional resources

- Learn more about Brazilian wandering spiders from the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

- Read about several species of Brazilian wandering spiders, including several images of the arachnids at the University of Florida.

- Find a spider in your bananas? It may or may not be a deadly species, according to the University of California, Riverside.

This article was originally published on Nov. 20, 2014.