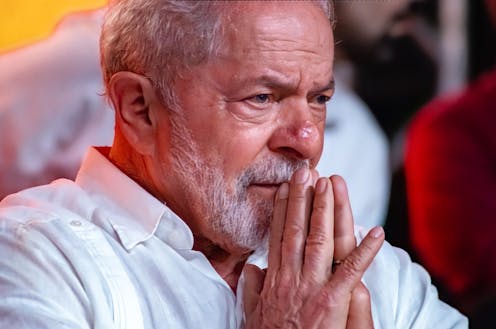

The newly elected president of Brazil is an experienced politician, having already served two terms in the role. But Lula da Silva will take the reins of a country that looks very different from the one he presided over before.

Much of this change was caused by COVID. Brazil had the world’s second-highest death toll (after the US) and the government spent about US$60 billion (£52 billion) in mitigation measures, including cash transfers to the poorest.

Such high levels of public spending by President Bolsonaro (which some viewed as a ploy to boost his popularity ahead of the 2022 election) have significantly deepened the country’s level of debt.

Now the country faces a serious economic hangover. Restoring fiscal sustainability is Lula’s first major task, as he attempts to strike a difficult balance between protecting the poor and ensuring sustainable public finances.

The international context for this could hardly be more challenging. Global levels of inflation and interest rates, as well as supply constraints caused by Russia’s war with Ukraine have drastically increased the cost of imported goods.

In the past, high commodity prices had supported Brazil’s growth, given its substantial exports of things like iron and oil. But the situation today is very different. China, Brazil’s largest trading partner, has seen a cooling of its economic growth, and the price of those same commodities has decreased.

Added to this, Brazil remains a relatively closed economy that has failed to diversify away from mining and agribusiness. And while the farming industry accounts for over a quarter of Brazil’s GDP, with the country’s exports of crops and meat totalling US$100 billion in 2021, the sector does not have enough scope to provide new jobs, limiting national prospects of employment recovery.

Despite a recent decrease, unemployment levels in Brazil remain high. And combined with inflation rates of around 8% this year this is hurting the poorest most, causing 33 million Brazilians to go hungry – an increase of 14 million compared with two years ago.

But Lula has some form in this regard. While in office from 2003 to 2011 he was credited with lifting 33 million people out of poverty, reducing extreme poverty by 25%, and expanding access to healthcare and education.

Now protecting the poorest and most vulnerable could not be more urgent – but the global and national economic picture gives him little room for manoeuvre. One option open to him is to focus on attracting green international investment by developing Brazil’s flourishing renewable energy sector and acting quickly on his campaign promises to eradicate deforestation in the Amazon.

But Lula will need to reassure investors over his broader vision and economic plans. During his campaign he promised higher welfare spending and higher investment, but also fiscal responsibility. There have been no indications of how he will pay for his spending wish list so far.

Negotiation over confrontation

Yet his commitments to prosperity and the protection of the Amazon seem sincere. Within hours of winning the presidency he pledged to halt the destruction of the rainforest and restore Brazil’s credibility as an international leader on climate issues.

These are immense tasks. Bolsonaro was elected on an anti-environmental platform back in 2018, and deforestation had soon reached its highest level in 15 years. Every day, an area of the Amazon the size of 2,000 football pitches is eradicated and prepared for crops or pastures.

The Bolsonaro government weakened environment protection agencies at the same time as it empowered the powerful agricultural industry that harms indigenous people and the forest they live in. Some environmental experts have argued that, while the goal of zero deforestation is credible, it is practically impossible within the next decade.

Brazil is also deeply divided after four years of polarisation and political violence. Nearly half the country did not vote for him, and many did so only to keep Bolsonaro out. The fact that many pro-Bolsonaro politicians were re-elected means the new president will have to make concessions and secure the support of opposition parties if he wants to implement changes.

Equally important is the need to consolidate Brazilian democracy after years of erosion. Bolsonaro implemented a massive return of the military to national political life. Today they occupy more positions in the public administration than during the 1964-84 dictatorship.

Establishing the preponderance of civil power over the Armed Forces is crucial for the democratic strengthening of Brazil.

A glimmer of hope lies in the fact that as one of the few heads of state to command respect from nations as diverse as the US, China, Germany and Russia, Lula may prioritise negotiation over confrontation. In a polarised world maybe he is the one who can promote peace and stability, and live up to some of the great expectations Brazilians have placed on his shoulders.

Nicolas Forsans does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.