Brandon Staley’s quest to destroy NFL secondaries in 2023 began with his love of the Chicago Bulls in the 1990s.

Their guard play was exceptional and, when considering their size for the era, most of them were outliers. Michael Jordan, Ron Harper and Scottie Pippen were all 6'6" or taller, allowing the entire offense to play a hybrid style of basketball—multiple players slashing, driving, shooting and playing inside—at a time when the game was more positionally rigid. The team could dictate their own matchups, placing players with advantageous traits on defenders ill-prepared to counter them (a faster guard drawing a slower forward, a bigger guard drawing a smaller guard, etc.).

His hypothesis—that this could be applicable to the Chargers—was solidified during a predraft visit with the Warriors before their Game 3, first-round matchup with the Kings in April (Staley and Warriors head coach Steve Kerr are friends). It’s about being large, handling the ball and spacing it all out efficiently. Size, he says, increases your margin for error.

Staley says over the phone a few weeks into training camp: “I’ve always wanted a receiver group built like that.” During the coaching interview process in 2021, when Staley was a burgeoning commodity, he felt the Chargers were the most fertile place to implement an offense that can “change the spacing on the field.”

A week after the Warriors defeated the Kings en route to a surprise conference semifinal berth, the Chargers were on the clock with a handful of needs and a 6'3" wide receiver from TCU on the board, Quentin Johnston. On tape, Johnston looks a little like Kevin Garnett in football pads. In Staley’s mind, he’s picturing slotting Johnston next to Mike Williams (6'4"), Keenan Allen (6'3"), Donald Parham (6'8"), Gerald Everett (6'3") and Joshua Palmer, who, despite being the runt of the group, is a solid 6'1" with thickness and a diverse route tree, and is discussed by his coaches as a fourth starter of equal importance to what they are trying to present.

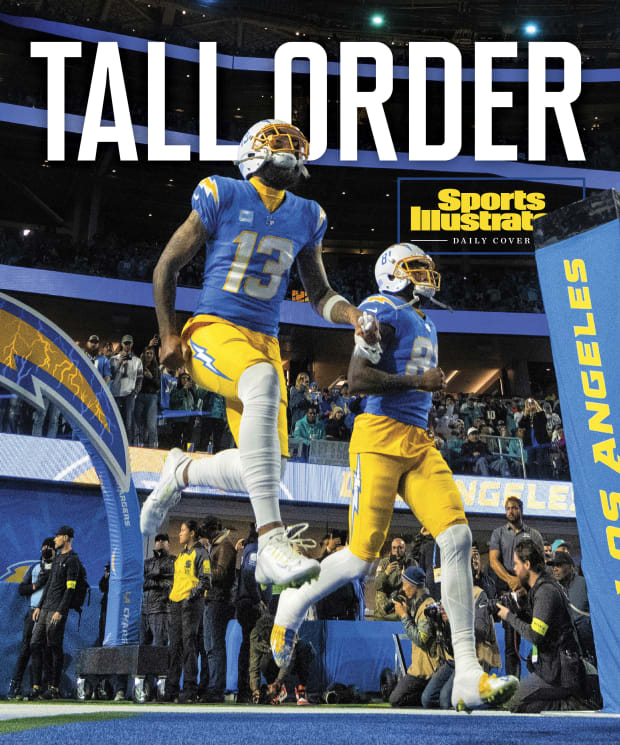

Kyusung Gong/AP

Having been a defensive coach for the majority of his career, Staley says he’s aware of how one player of that size alters the mathematics of a defense given the extra defenders it likely takes to cover just one person.

“Now, if you’ve got two of those guys, what does it do?”

He keeps going …

“Now, if you’ve got three of those guys, and one of them is among the best slot receivers to ever play, Keenan Allen, that’s when it gets tough out there. The nickels in this league are 5'10", 5'11" at best.”

There are currently three projected starting cornerbacks in the Chargers’ division who are 6'0" or taller. I asked Staley whether the Chargers mapped out the remainder of the schedule as a kind of analytical exercise heading into the draft. He said—confidently—that they didn’t need to.

“It just doesn’t exist,” he says of the requisite size at the position. We spoke just days after Johnston ran a deep route in the preseason against Rams defensive back Tre Tomlinson, who is generously listed at 5'9", drawing a chuckle from the broadcast crew.

Welcome to Staley’s search for new heights. At a time when one specific kind of receiver and a few specific kinds of offenses are seemingly coveted league wide—more on that shortly—Staley and his staff are borrowing more from modern basketball. It’s not only to use size to stress the limits of a defense physically, but also to space out that size to consistently disrupt the comfort of defensive backs. Size not only gives Los Angeles a margin for error, but it will also lighten the number of players defenses can put in the box, it will force defenses to constantly fear the deep shot (thus hampering their ability to cover option routes being run by the second and third wide receivers), it will result in more pass interference penalties called in its favor and, most notably, it will demoralize secondaries when the true reality of the situation hits. Quarterback Justin Herbert can put the ball almost anywhere, and if all of his receivers are bigger than all of the corners, he can almost certainly put the ball where your defense is not, even if the defense is playing it perfectly.

“Defensively, it becomes a lot more challenging when we’ve got a basketball team out there,” Staley says.

Williams put it more bluntly: “I don’t want to spill too much, but just know there’s going to be some numbers put up.”

“It’s interesting,” Staley says. “A lot of the guys in the NFL that people consider great offensive coaches, Kyle Shanahan, Sean McVay, Kevin O’Connell, Mike McDaniel—guys who are good friends of mine—the kinds of receivers they are looking for, I haven’t believed in that.”

Staley said he was specifically referring to the “multicut route runner, who can run the whole [route] tree.” While he did not name any specific receiver (and, tonally, was not denigrating any of these players, just simply stating a preference), I would assume he’s referring to players with a similar scouting report to a Brandon Aiyuk, a 6'0" wide receiver Shanahan drafted in the first round of the 2020 draft.

He pointed out that the best receiver Shanahan ever had was Julio Jones while serving as the offensive coordinator for the Falcons. In Jones’s prime, he was a bruising, physical pugilist at 6'3". He was talented and versatile, but he was also massive.

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated

“Julio changes everything because of his size,” Staley says.

In a typical Shanahan offense and, to some degree, a McVay offense, they often played from a more condensed formation, which presented its own unique challenges to a defense. With the Rams, there is often an explosion of activity at the point of a handoff or fake handoff that prevents defenders from properly gauging the direction of a play. The Rams’ best blocker may also be their best wide receiver in Cooper Kupp. Thus, it makes more sense to play Kupp a bit like a hybrid tight end and pass catcher closer to the offensive line. It also doesn’t make sense to motion a receiver way toward the sideline when the beauty of their sweep action is the immediate threat of something happening when the receiver is behind the quarterback. In San Francisco, their speed is accentuated by bunching defenders together like herded cattle in the box. A tight formation packs linebackers, safeties and corners inside, and a rocket-boosted running back taking an outside handoff suddenly has all sorts of daylight.

“What we’re trying to do is change the spacing of the field by who we’re putting out there and who you have to defend,” Staley says. “But we don’t want to bring size in closer; we want to spread it out.”

Think wider splits. Think more occupied space, which expands and perforates a defense like a piece of chewed gum.

Which brings Staley back to his first love, basketball, the Bulls, Steve Kerr and the Warriors.

“Everything has gotten so spread out because of [the increase in volume and accuracy of three-point attempts],” he says. “So it changes the spacing of the defense and how you have to play defense. Everyone has to be accounted for. And when you account for the three-point shot, it opens up more space to drive the basketball.”

A three-point shot for the Chargers is going to look a lot like Herbert uncorking a 20-yard pass down the sideline. Staley’s equivalent of driving the basketball? Running against defenses that, mathematically, are going to struggle to present more than six defenders in the box because they need more help in the passing game, which gives a five-man offensive line, a sixth eligible blocker (a tight end) and Pro Bowl running back Austin Ekeler a marked advantage. That, or perhaps dumping the ball over the middle to Williams and Palmer, who are a chore for defenders to bring down at full velocity.

“There’s going to be a mismatch somewhere,” Staley says. “Whether it’s in the slot or out wide, maybe they have one good corner, and they can match up with one of the guys outside. Well, they won’t have two [good cornerbacks]. If they do, are they going to have a nickel corner who can match up with Keenan [Allen]? That’s going to be the game they have to play.”

Staley and his coaches also believe this is true because, like Chicago’s trio of guards, each of them has different ways of bypassing a defender. Williams, for example, knows his strength is in body positioning. Johnston can reach top linear speed faster, which means defenders are wary of his immediate burst at the line. Allen is a footwork specialist, which means he uses precision steps to evade a defensive back at the line.

“We have everything you want in a starting five,” Allen says. “We have constructors, and, for the receivers, I’m the point guard.”

This offseason, when the Chargers changed offensive coordinators and brought in former Cowboys play-caller Kellen Moore, there also emerged a desire for each of the wide receivers to learn every position on the field. There are conflicting theories within the sport as to best practices. For example, many receivers coming out of college in speed-dependent, up-tempo offenses are assigned to only one position, thus making their transition to the NFL and multiple-receiver spots difficult. Some coaches opt for efficiency and the mastery of one space at the NFL level by keeping a player in that same space. (Allen, this offseason, told reporters that he almost never left the slot under former coordinator Joe Lombardi. Lombardi, now with the Broncos, had success in Los Angeles despite the ouster and oversaw passing seasons of 5,014 yards and 4,739 yards despite rarely having Allen and Williams healthy together.)

The advantage for the Chargers as a kind of positionless unit is the ability to match up one defensive back with three or four different receivers over the course of a game who each have a completely different way of getting open. On top of the built-in height advantage, there is also a stylistic one.

I asked Staley whether he was stealing from a different sport aside from basketball here. A trend in modern baseball has been the more constant changing of pitchers so that batters cannot pick up on trends or get comfortable. Isn’t it similar to—on a series of three plays—having a defensive back face your equivalent of a burner, a finesse-type player and a sledgehammer?

“That’s the nature of it. You’re not going to get used to the matchup,” Staley says. “We’re changing the pace on the defense in more ways than one.”

He illustrates the point with an example.

“Let’s just say, with Keenan, you felt like you had a way to cover him in the slot or something. Whether it’s man-to-man or zone. All of a sudden, all we need to do is motion him to the [No. 1 receiver spot], and now he’s isolated on a corner. Let’s say we’ve cut the split where Keenan has a free run at the cornerback; he can use all his moves, and the cornerback can’t press [a technique where the defender gets up in the receiver’s space and utilizes his hands to slow the receiver down]. That’s not good for them.”

John McCoy/Getty Images

Chris Beatty is the Chargers’ wide receivers coach. In previous iterations of his football life he was a high-scoring offensive coordinator at Hampton (where one year he sent more players to the combine than USC) and a wide receivers coach with a string of success stories, from DJ Moore to Tavon Austin to Maurice Ffrench who, while not a household name, broke Larry Fitzgerald’s single-season reception record at Pitt with Beatty as his position coach.

Staley met Beatty when they worked together at Northern Illinois. He was one of Staley’s first phone calls when he received the coaching job in Los Angeles in 2021.

“He’s one of the top coaches I’ve ever worked with,” Staley says. “He’s going to be an offensive coordinator in this league soon.”

Beatty promised Williams he would have a career year during their first season together, which Beatty backed up. Williams finished the season with a career-best 76 catches, a career-best 1,146 yards and nine touchdowns, one behind his career high.

This is because Williams was the foundation of the Chargers’ height experiment. While Allen was already a well-versed route runner, Williams, like a lot of taller wide receivers who come out of college, got pigeonholed as a boom-or-bust specialist who almost exclusively ran deeper routes outside the numbers. The NBA’s equivalent would be a dying big-man center such as Patrick Ewing or Hakeem Olajuwon.

So, he and Beatty worked to re-expand his repertoire. By the third week of the 2021 season, Williams’s quick-slant route, almost never respected by defensive backs because he never ran it, was the grist for an epic double-move touchdown (the slant was respected, and thus, when faked, fooled the defender into barreling down inside before Williams sprinted straight ahead) against the Chiefs.

“[Coach Beatty] wanted me to get paid,” says Williams, who signed a three-year, $60 million contract last year. “He kept it simple but pushed us.”

I asked Williams, the seventh pick in the first round in 2017, when he felt he was finally reaching his potential. “When I started getting used a little different,” he says. “You get one-dimensional and you get easier to guard. It stopped being, ‘Oh, he’s about to run a go route, so we’ll play his outside shoulder. Now, they have to respect the inside.”

This is the granular piece of Staley’s strategy. In the NBA example, the height advantage doesn’t work unless the bigger players learn how to shoot, run faster and handle other responsibilities not typically assigned to people that size such as the point guard position. The Chargers are not a threat unless big receivers can run the same route tree as a smaller one. Johnston is in the midst of that transition now, having been fed a crossing route in the team’s preseason opener against the Rams in an effort to get him the ball with space to run over the middle. The plan is to bring him along slowly, knowing that receivers such as Palmer give the Chargers an extended window of time for development.

“He was no huddle most of the time in college,” Beatty says. “He ran off signals. But he’s doing a good job with it. He’s working hard. And that’s why they call you a coach, right?”

He added: “We don’t want to limit anything Quentin is doing. There’s a huge learning curve, but that was the whole deal with Mike. Mike was asked to run outside the numbers all the time, and I was like, ‘He can do more than that. We just have to ask him.’ I don’t see it being any different for Quentin.”

Beatty has adapted his methods to each receiver’s individual needs, getting to know them on a personal level. Williams, he says, is more of a doer. Beatty can describe how he wants it done and send the receiver off. Allen, he says, is a suggester. Allen, who came into the league in 2013 and made five consecutive Pro Bowls from ’17 to ’21, has seen almost anything possible a defense can do to him. His relationship with Beatty is more of a peer-to-peer one that includes the lobbing of ideas back and forth.

“I’m learning how to pick up on Quentin,” Beatty says. “I’m learning what’s best for him, because coaching is learning, too.”

With all of their combined size and athleticism, one would assume the Chargers’ receiving corps would allow little drips of it to spill out into normal human life. Think, an Olympic sprinter who runs a sub-10-second 100-meter dash to catch a bus, or Magnus Samuelsson one-handing a dishwasher at Lowe’s.

I asked Williams about any epic basketball games in the facility, hoping for a completed metaphor about Los Angeles’s search for height-centered innovation. A volleyball spike? An easier time changing a light bulb? Anything?

“Uhh, we went bowling one day?” Williams says. “I haven’t been bowling in like two years, but I think I finished in second place, though.”

Close enough. During that team-bonding exercise, Williams says, they all worked through the experimental phase en route to higher scores.

“We all got our game,” Williams says. “We all change our technique every game. Then, you might find something that works and you stick with it.”

Staley is betting on it.