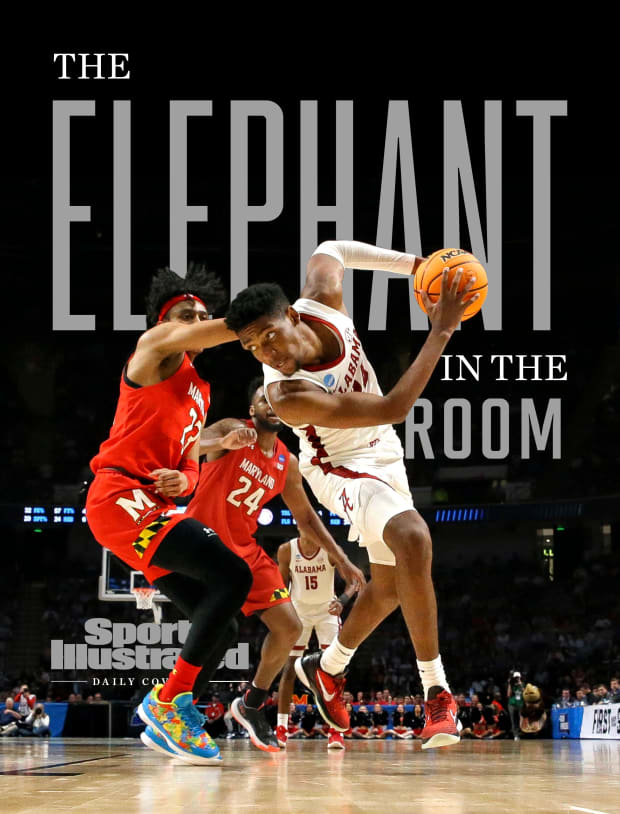

With under 16 minutes to go in its NCAA tournament second-round game against mighty Alabama, Maryland still harbored hope. The Terrapins trailed the No. 1 Crimson Tide by seven points in Birmingham’s Legacy Arena, and guard Jahmir Young was sprinting toward the basket for a layup that could have cut the deficit to five.

The next eight seconds extinguished that hope. Alabama star Brandon Miller came soaring in to spike Young’s layup attempt, then immediately turned and sprinted down the sideline as teammate Mark Spears grabbed the ball and started a fast break. Seventy feet later, Miller took a pass in transition from Sears, rose in one fluid motion on the wing and flicked his right wrist. The three-point shot splashed, the arena erupted, Bama then led by 10 and the game was effectively over. The Tide rolled on.

If you want a distilled snapshot of why Alabama has refused to bench Miller after he played a role in a fatal shooting in Tuscaloosa on Jan. 15, those jaw-dropping eight seconds are it. The slender, 6'9" freshman—compared by some to six-time NBA All-Star Paul George—is the most talented player in men’s college basketball and projected to be a top-five draft pick come June. He has lifted the Crimson Tide to Southeastern Conference regular-season and tournament championships, their first NCAA tourney No. 1 seed and now within reach of their first Final Four and men’s basketball national title.

Miller is, simply, a program-altering talent. And the school is going to ride him as far as it can, controversy be damned, no matter what the rest of the nation thinks of it.

Gary Cosby Jr./Tuscaloosa News/USA Today Network

“It’s a moral dilemma of the highest order,” said one NBA scout shortly before watching Alabama play earlier this month. The NBA’s dilemma is the draft evaluation of Miller, which would be extremely simple if not for the fact that he drove a weapon to the scene of a fatal shooting after receiving a text from his now former teammate asking for the gun.

“Miller is the epitome of new-age basketball, which is why he is arguably the most unguardable player in the college game,” says a second NBA scout. “It’s practically impossible to see him failing, in a sense, with the NBA level in mind. He is just too dynamic, big and versatile with his offensive game to see failure ahead.

“I guess the only inherent risk—to the naked eye at this moment—is the cold, hard facts related to the off-the-floor incident. Is there more to come from that, or is there a trickle-down related to it as far as off-the-floor red flags? Is there more to Miller and his background? How does he handle his circle when he does make the big bucks? Is he a follower who finds it hard to say no to the wrong people?”

The NBA folks have a few more months to figure it out. The more immediate dilemma is how college basketball fans should view this Crimson Tide team.

The parallel story lines involving Alabama have suffused the customary joy of a March Madness run with tension. Miller was accompanied by armed security at the arena in Birmingham last week, with coach Nate Oats alluding to online threats the player has received. Miller and Oats have tried to use canned answers to pointed questions in press conferences. There is an elephant in the room, and it’s not Alabama’s mascot.

This is a great team, one Maryland coach Kevin Willard compared to the mid-1990s Kentucky juggernaut. Oats has built a team around an up-tempo offensive philosophy that is heavy on three-pointers and drives to the rim—but the Tide might be even better defensively, thanks to their athleticism and length. Viewed through a basketball lens, they are a blast to watch.

Yet it’s impossible to separate the on-floor product from the shooting death of a 23-year-old mother, Jamea Jonae Harris, and the Tide’s involvement in that episode. According to law enforcement officers, Miller provided then-teammate Darius Miles with the weapon used in the killing. Miles has been charged with capital murder after being alleged to have given that gun to his friend, Michael Davis, who is alleged to be the trigger man in the shootout. Miller and teammate Jaden Bradley were at the scene that night—news that spilled out of a pre-trial hearing in late February.

Miller’s attorney, Jim Standridge, has stated Miller had no prior knowledge Miles and Davis had been involved in a verbal altercation that led to the shooting. “Brandon never touched the gun, was not involved in its exchange to Mr. Davis in any way, and never knew that illegal activity involving the gun would occur,” Standridge’s statement read.

The conflicted response to the Crimson Tide can be seen, in part, in voting for national awards. Without the off-court baggage, Miller would be a lock for first-team All-American honors and a strong favorite for national Player of the Year. He fits the established POY formula: 19.1 points per game, 8.2 rebounds, star player on the No. 1 team, big performances in high-profile games and so on.

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

But Miller was not a first-team All-American in the U.S. Basketball Writers Association voting. (He was the organization’s national Freshman of the Year, an area in which there was simply no realistic competition.) Nor is he one of four finalists for the Naismith Player of the Year Award. Miller was originally left off the Wooden Award Player of the Year list of 15 finalists but later was added. Nor has Oats received much Coach of the Year support, despite taking a team picked 20th in the preseason AP poll to No. 1 and a team picked to finish fifth in the SEC to a runaway league title. The SEC coaches voted for Vanderbilt’s Jerry Stackhouse and Texas A&M’s Buzz Williams as co–Coaches of the Year. The USBWA’s national COY is Marquette’s Shaka Smart. It would be a surprise if Oats garners any of the remaining coaching honors.

If Alabama perceives itself slighted in terms of awards, the program has at least shown the good sense not to complain publicly about it. It’s one of the few areas in which the school has not flunked PR 101.

The Tide have been blundering their way through the fallout from the Miller revelations ever since they blew up. The university has been in damage-control mode for a month straight, with much of the damage self-inflicted. There has been an astounding succession of brushfires followed by attempted counter spin.

On Feb. 21, a Tuscaloosa detective testifying in a pre-trial hearing first ripped the lid off the story by linking Miller and Bradley to the scene of the shooting. This seemed to catch Alabama completely unaware—athletic director Greg Byrne was having a medical procedure done that day, and Oats responded to questions about Miller’s involvement with a dismissive “wrong spot at the wrong time” comment that has lived in infamy.

That was the first day of damage control: Oats apologized for his comments, attempting to strike a sympathetic tone regarding Harris’s death. Byrne subsequently said during an ESPN podcast that the school had stayed out of any fact-finding regarding the criminal investigation and thus didn’t know many details about the players’ involvement. That lack of knowledge never stopped the team from playing Miller and Bradley while waiting for information to develop.

The most recent dust-up was either a colossal misunderstanding or a calculated shot at Oats from none other than Nick Saban. After incoming freshman football player Tony Mitchell was arrested with another man on charges of driving more than 140 mph while in possession of a “significant amount of marijuana, a set of scales, a loaded handgun between the passenger seat and center console and a large amount of cash,” Saban suspended him and made some striking comments.

“Everybody’s got an opportunity to make choices and decisions,” Saban said Monday. “There’s no such thing as being in the wrong place at the wrong time. You’ve got to be responsible for who you’re with, who you’re around and what you do, who you associate yourself with and the situations that you put yourself in. It is what it is, but there is cause and effect when you make choices and decisions that put you in bad situations.”

This seemed like a clear reference to what has been the most incendiary sentence uttered by anyone in college athletics in 2023: Oats’s “wrong spot at the wrong time” dismissal of Miller’s involvement in the shooting. But as Saban’s words rippled through the media, Alabama administrators stressed behind the scenes that there was no intentional comparison by the football legend to Oats’s words and nonactions.

Saban took no public steps later Monday or at any point Tuesday to clarify the interpretation of his comments or walk them back. Then, on Wednesday, Alabama produced a propaganda masterpiece on social media: pictures of Saban meeting with the Crimson Tide basketball team, including one photo of a smiling Saban giving a thumbs-up in the company of a smiling Oats.

On Thursday, both coaches addressed their relationship.

“I’m really thankful for the support that he has given us and continues to give us with the basketball program at Alabama,” Oats said.

“I don’t make comments about anybody else, and we hope the basketball team does really, really well,” Saban said at the football team’s pro day in Tuscaloosa.

Alabama law professor emeritus Gene Marsh, a past chair of the NCAA Division I Committee on Infractions, believes Saban’s comments were entirely without regard to the Tide’s basketball situation.

“Nick Saban has said something like that many times—about choices we all face and consequences,” Marsh says. “He makes that a regular message to his team. I doubt he was even thinking about basketball. He doesn’t need to think about basketball for any reason. He stays in his own pew or lane or whatever.

Vasha Hunt/USA TODAY Sports

“Either Alabama basketball players never got that message, or they did not fear repercussions.”

Alabama basketball has seemingly been missing the message for weeks. Four days after the Miller link to the murder investigation exploded, during a home game against Arkansas, the Tide lit the internet on fire with its pregame introductions. Video circulated of Miller’s pregame introduction routine, which the school said he had been doing all season: a teammate patting him down, as if searching for a weapon. It was, at the very least, incredibly callous.

The damage control that day: Oats tried to explain away the gesture as a TSA pre-flight security check and “being cleared for takeoff.” That fell on unsympathetic ears, since any pre-flight security check is, of course, a weapon search. Oats apologized and said the pregame introduction routine would cease immediately.

When Miller finally did speak to the media, about two weeks after being linked to the murder investigation, he had been fully coached up on what to say and not say. “I never lose sight of the fact that a family has lost one of their loved ones that night,” Miller said before the SEC tournament. Beyond that, he’s largely declined to comment or said he was “leaning on my teammates.”

Oats, meanwhile, has consistently come across as oblivious. At one point in the SEC tourney he said, “All our kids are pretty high-character kids,” while a player who was on the team until mid-January is facing a murder charge. Last week in Birmingham, his characterization of Miller sounded almost like he was describing a victim: “He’s a really good kid that I think’s done a really good job of handling a heartbreaking situation that we all know is very tough. So, you know, we just see him show his mental toughness throughout the year. I think we’ve all seen it.”

There is a striking disconnect between Oats’s basketball reputation and what’s become of his leadership rep.

In terms of X’s-and-O’s strategy and recruiting, the 48-year-old has been on the cutting edge. A high school coach and math teacher in Michigan just 10 years ago, Oats was hired to be an assistant at Buffalo by Bobby Hurley and, when Hurley left for Arizona State, Oats was promoted to the head job. He took the Bulls to three NCAA tournaments in four seasons, advancing to the second round twice and becoming one of the hot names for power-conference jobs.

Alabama landed Oats, and he quickly went to work on the recruiting trail. Among the players signed in his first full recruiting class: Miles and Joshua Primo. Miles, you now know about, and not for anything he achieved on the court. Primo, an athletic wing from Canada, played one season for the Tide before being selected with the No. 12 pick in the 2021 draft by San Antonio.

After showing potential in his rookie season, he was waived in October 2022 for exposing himself to a team psychologist during counseling sessions, the psychologist alleged. She sued the team and Primo; the former suit was settled out of court and the latter was dropped, according to reports. Primo has not been picked up by any NBA team since being waived.

That 2020–’21 Alabama team cemented Oats’s on-court credentials, with an SEC tournament and a No. 2 NCAA tournament seed. The Crimson Tide was upset in overtime by No. 11 seed UCLA in the Sweet 16, but Oats already had earned a contract extension through ’27 during the season.

By then, Oats already had won a fierce, old-school SEC recruiting battle for five-star guard JD Davison of the 2021 class. But Davison didn’t deliver as much as hoped on the floor as Alabama went 19–14, made the tourney as a No. 6 seed and was upset by Notre Dame in the first round. Davison turned pro and was a late-second-round pick.

The more important piece of that 2021 recruiting class would turn out to be four-star center Charles Bediako. He has become the anchor of the current Alabama team’s impenetrable interior defense and a major reason why the Tide are ranked third nationally on defense, according to Ken Pomeroy’s metrics.

“They have a very simple game plan, which works,” Willard says. “They just funnel everything into the big guy. … They use their length tremendously.”

The star recruit of 2022 was, of course, Miller. The five-star prospect visited multiple SEC schools and Kansas, but chose the Tide over a couple of pro alternatives. Upon his arrival in Tuscaloosa, Miller was expected to be an instant-impact player, but his rapid development from a potential ’23 second-round pick to a top-five prospect and college superstar was a revelation.

Miller was a perfect fit in Oats’s scheme. He can shoot with devastating accuracy, handle and drive with both hands, and is a willing rebounder and quick jumper.

“When he is not making shots, he is rebounding and starting the early offense,” says an NBA scout. “That flows into maybe the most underrated aspect of his game—the high-ball-screen playmaking.”

With Brandon Miller as the centerpiece of Nate Oats’s modern program, there may well be no stopping Alabama this week in the Sweet 16 or next week at the Final Four. The entire university is all in on this title chase; the question is what the cost has been.