On a hot Saturday in San Antonio over 10 years ago, an 8-year-old boy was rushed to the hospital after days of fever, headache, vomiting and sensitivity to light. The child's mother, who lived near the Texas-Mexico border, had taken him to a series of clinics in Mexico, but his condition had worsened. The child was now unconscious and unresponsive to sound, light or other stimuli.

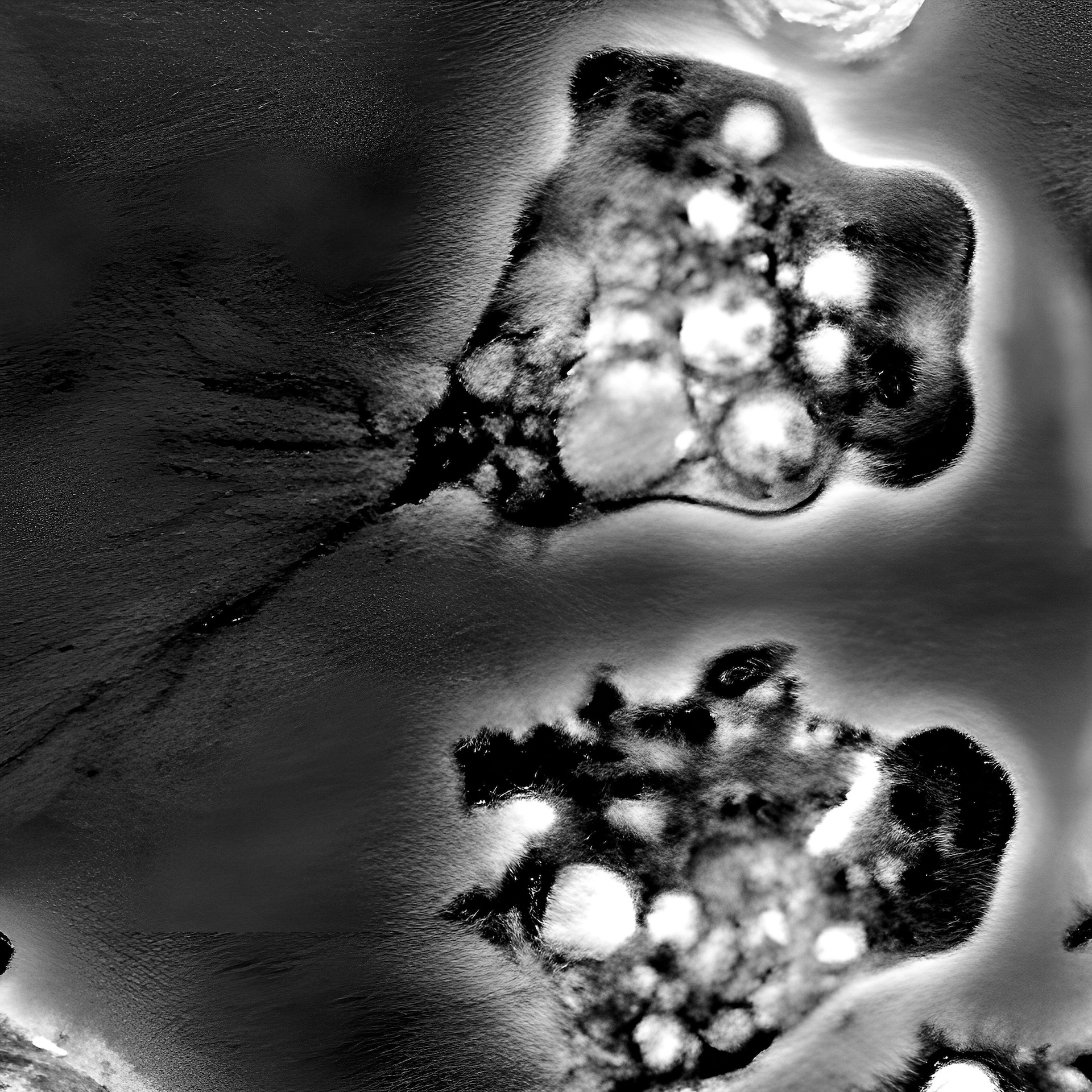

Doctors put the child on a ventilator and began a breakneck effort to find out what was wrong. What they discovered, swimming in the boy's cerebrospinal fluid, was an organism that left little room for hope: Naegleria fowleri, more popularly known as a "brain-eating amoeba."

It was the third case that Dr. Dennis Conrad, a pediatric infectious disease specialist, then at University Hospital in San Antonio, had ever seen in his career. The other two patients had died.

But Conrad had recently read that a new drug option, miltefosine, had been approved as an experimental treatment for N. fowleri infections. He added it to the boy's drug regimen, which already included other antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory medications.

"It's the kitchen sink," Conrad told Live Science. "It's a bad disease, and you just hit them with everything you can think of."

The child's prognosis was grim. He had been sick for five days before arriving in San Antonio, and most people who contract an infection with N. fowleri die about five days after symptoms start. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were 157 confirmed human cases of N. fowleri infection in the United States between 1962 and 2022. Four survived.

Elsewhere in the world, the numbers are similar. It's rare to become ill from an infection with this amoeba — and it's very, very rare to survive. But the few recent survivors may owe their recovery to miltefosine, the most recently recommended new medication for primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), the disease caused by the amoeba. New drugs may be on the horizon as well. The question is whether they can reach patients before the damage is done.

'A bull in a china shop'

N. fowleri thrives in warm fresh water around 80 degrees Fahrenheit (26.6 degrees Celsius) or warmer, although it might manage to hang on in cooler temperatures, too, according to the CDC. It infects people purely by accident, when water is forced up the nose, driving the amoeba through a lacy bone called the cribriform plate to the olfactory nerve, which acts as a highway to the brain.

Immunocompromised people are at higher risk, said Dr. Juan Fernando Ortiz, a neurology resident at Corewell Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan, who wrote a journal article about treating the infections. Boys under age 14 make up a disproportionate number of cases, according to the CDC, perhaps because they're more likely than other groups to do things that push water up the nose, like jumping and diving. Most cases involve natural bodies of water, but cases have rarely been linked to treated water, such as in splash pads. In a few cases, people have gotten infected by using tap water in neti pots to rinse their sinuses.

The child Conrad and his colleagues were treating in August of 2013 had a tragically typical story of infection. He had spent the summer with his mother at an informal camp on the banks of the Rio Grande, where there was no running water. People bathed in the river, and the child enjoyed splashing in the shallows there.

Most likely, that's where he encountered the amoeba, which Conrad and his team now had to kill — before it could wreak more havoc than the child could survive.

PAM kills by massive destruction of brain tissue. The amoeba itself does some of the destruction directly, giving it the "brain-eating" moniker, but much of the brain damage is actually caused by the body's aggressive immune response to an intruder in the control system, Conrad explained. Parasites that evolve to live inside a body usually have ways of tamping down their host's immune response so they don't lose their meal ticket, Conrad said. But because N. fowleri has no need for a host, it has none of those adaptations. "It's a bull in a china shop," Conrad said.

Fortunately, there are only between zero and six N. fowleri infections in the U.S. each year, and there is no evidence that infections are becoming more common, said Dr. Julia Haston, a medical epidemiologist with the CDC's Waterborne Disease Prevention Branch. Although most cases occur in Texas, Florida and other Southern states, there have been more cases than usual in the northern U.S. in recent years, perhaps because climate change is warming waterways to the temperatures that the amoebas favor, Haston said, and a 2021 study found cases increasing in the Midwest as far north as Minnesota.

"The safest approach for people wondering whether they're at risk … is just to assume that Naegleria fowleri amoebae are in all fresh water," Haston said. "Lakes, rivers, any naturally occurring freshwater body."

A Hail Mary works

To battle the amoeba that was attacking the San Antonio patient's brain, Conrad and his team pulled out a then-novel treatment, miltefosine. The drug, an antimicrobial originally used to treat leishmaniasis, an illness caused by a tropical parasite — had shown promise against N. fowleri in studies, so the CDC had been distributing it for PAM cases. Miltefosine penetrates the blood-brain barrier and is relatively well tolerated by patients, Ortiz said. That's important, as many antiparasitic drugs also damage human cells, he added.

The doctors ordered the drug from the CDC. (Today, it's available commercially under the brand name Impavido.) It arrived 14 hours after the child was admitted.

The child lived.

But he was not unscarred. When the boy left the hospital, he could breathe on his own but not do much else. After months of rehabilitation, he regained some of his abilities, but his family still had to help him with basic self-care, Conrad said.

That same summer, however, a 13-year-old girl in Arkansas contracted the amoeba while swimming in an artificial pond. She received quick treatment, including miltefosine, and recovered. After six months of rehab, she had no lingering neurological effects from this brush with death, according to a 2015 case report describing her treatment.

She and the Texas boy were the first U.S. survivors of PAM since 1978. In 2016, a 16-year-old boy in Florida contracted PAM and received miltefosine; he also recovered fully.

However, not all PAM patients who have received miltefosine have survived. Even with the new drug, PAM has a fatality rate of over 97%, according to the CDC.

Each summer, a handful of new PAM cases pop up around the country, and doctors are continually working to improve their treatment. They're increasingly exploring strategies like cooling patients' body temperature to around 95 F (35 C), Conrad said, which some studies suggest might improve recovery from brain trauma.

There may be new pharmaceuticals on the horizon, too. Miltefosine can have toxic side effects on the kidneys and liver and isn't available in developing countries, said Jacob Lorenzo-Morales, a senior lecturer in parasitology and the director of the University of La Laguna Institute of Tropical Diseases and Public Health of the Canary Islands.

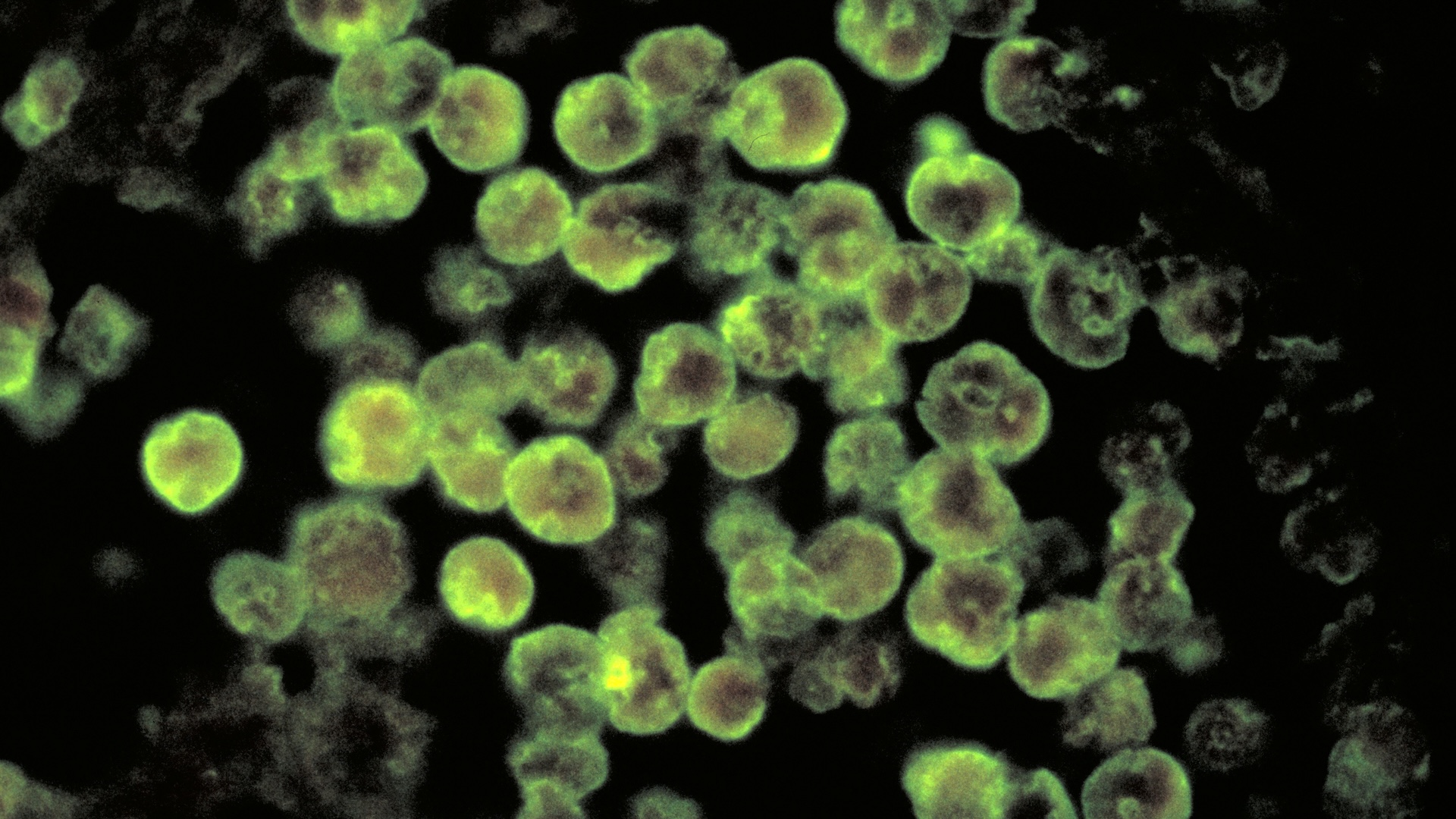

So Lorenzo-Morales and his team are looking for alternatives. One of the most promising is nitroxoline, an antibiotic used in Europe to treat urinary tract infections. Lorenzo-Morales and his team reported in the journal Antibiotics in August 2023 that in lab dishes, low concentrations of nitroxoline induced cell death in N. fowleri, without causing toxic effects on host cells. This drug has also been used to successfully treat one patient infected with a different brain-eating amoeba, Balamuthia mandrillaris.

Now, they're conducting animal studies and hope to present positive results at next year's international Free-Living Amoebae Meeting, a biannual meeting of amoeba researchers. Nitroxoline is already widely available worldwide, Lorenzo-Morales said, and because it is already approved for use, extensive clinical trials won't be necessary; doctors can begin using the medication off-label.

New alternatives

There are also efforts to find new medications that work against PAM. Some researchers are interested in developing mRNA vaccines against N. fowleri infection, with a 2024 study in the journal Scientific Reports using modeling of the amoeba's surface features to suggest what such a vaccine might look like. (The authors of that study did not respond to requests for an interview with Live Science.)

Lorenzo-Morales and his colleagues are also investigating the effects of a pigment called elatol, which is extracted from red algae. "We have isolated some key compounds from red algae that are very active against different free-living amoebas, including Naegleria, at concentrations that are even lower than the current treatments," he said.

However, the researchers are currently doing those tests in lab dishes. Moving testing to people will require funding from pharmaceutical companies. That can be difficult, Lorenzo-Morales said, because companies don't see a lot of potential for profit from a "rare" disease like PAM. However, he said, PAM still goes unrecognized far too often, he said, which may mean the potential market is bigger than pharmaceutical executives believe.

A race against time

Perhaps the most immediate hope for today's patients is simply recognizing the disease faster. The time to save someone with PAM is short, said Julia Walochnik, a professor of tropical medicine at the Medical University of Vienna who studies amoebic diseases. "If it's too late, it doesn't matter which drug is used; the patient will usually not survive," she told Live Science.

The late onset of treatment might be one reason why Conrad's 8-year-old patient sustained such serious brain damage while the other youth treated around the same time recovered more fully.

The test for the amoeba is simple: Take a sample of the fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord and look for swimming single-celled organisms. But doctors may not think to order the test in time, because PAM looks like meningitis caused by much more common viruses and bacteria. Families of children who have died of the disease are increasingly working to raise awareness, which could hopefully spur quicker diagnosis and treatment. For instance, the Jordan Smelski Foundation for Amoeba Awareness, started by the parents of an 11-year-old boy who died of PAM in 2014, hosts educational events for doctors and the public.

Awareness is making a difference, Lorenzo-Morales said. "Every time we have been involved in a clinical case in the last four to five years, the diagnosis has been fast," he said. "That didn’t happen before."