NASA's asteroid-deflection mission may have sent dozens of boulders on a collision course with Mars, a new study suggests.

In 2022, NASA deliberately crashed a spacecraft into an asteroid called Dimorphos in order to change its orbit, as well the trajectory of the larger space rock it circles, called Didymos. The mission, called the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), was designed as a kind of pilot program for deflecting potentially deadly near-Earth asteroids similar in size to the one that wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs.

Scientists considered DART a huge success; subsequent studies revealed that it altered the smaller asteroid's orbit by 32 minutes, and totally changed Dimorphos' shape.

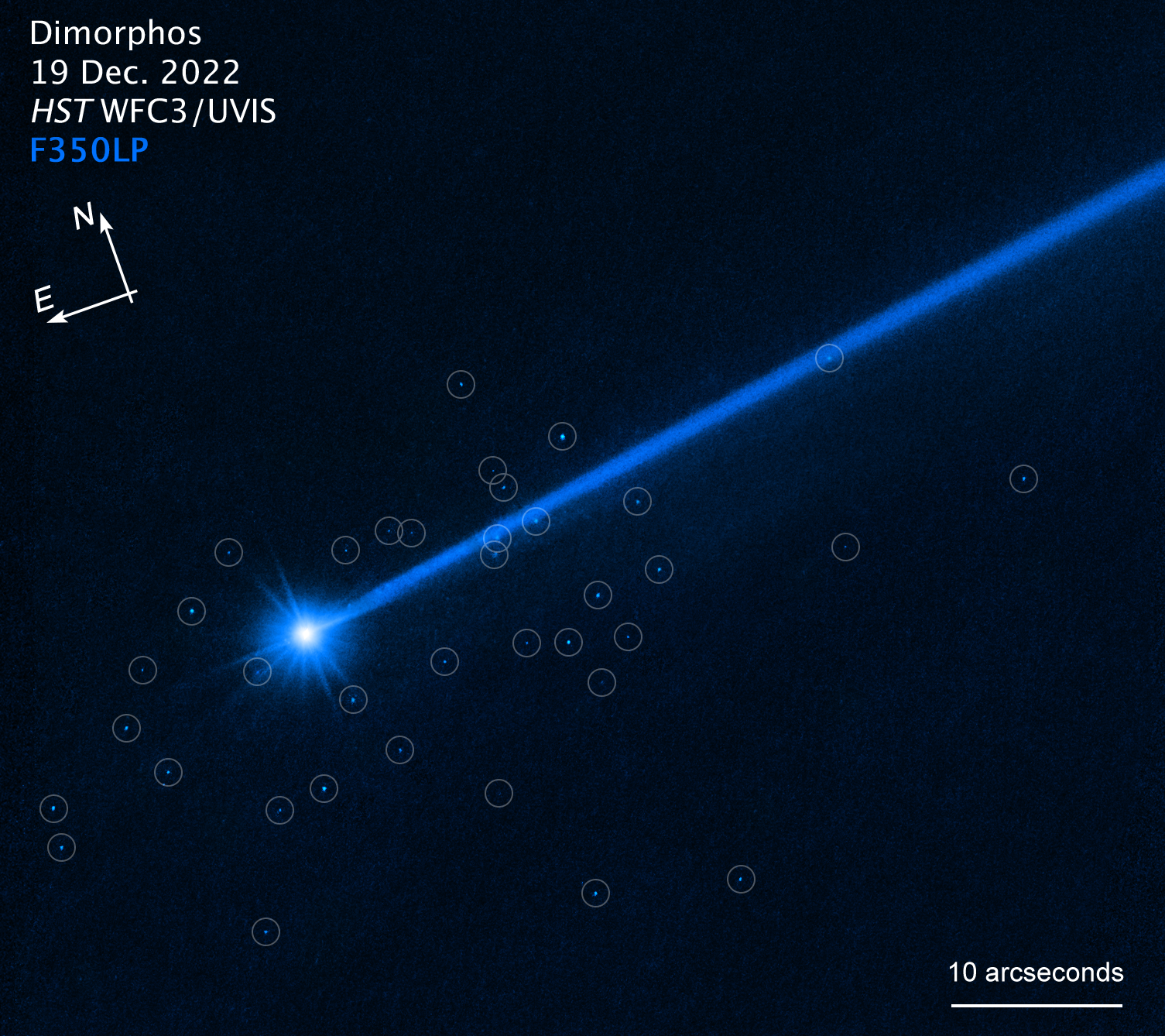

But the mission had an unexpected consequence: When the craft collided with Dimorphos, it sent a swarm of 37 boulders measuring up to 22 feet (6.7 meters) flying into the cosmos.

Related: 'Planet killer' asteroids are hiding in the sun's glare. Can we stop them in time?

"We did not expect that many boulders that were that big to be blown off," Andy Riven, an astronomer at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory and a member of the DART team, told National Geographic.

Thankfully, none of the boulders seem poised to strike Earth, but researchers were still curious where the giant rocks might end up. Now, they may have an answer. In a yet-to-be-peer-reviewed preprint paper, researchers describe the debris' potential destination: Mars.

Marco Fenucci, a mathematician at the European Space Agency's Near-Earth Objects Coordination Centre and co-author of the new study, tracked the trajectory of the boulders and ran simulations that projected their positions 20,000 years into the future. There are, of course, a lot of uncertainties involved in making such a far-flung prediction. However, Fenucci and his team found that in most scenarios, the boulders ended up crossing Mars' orbit in about 6,000 years.

Whether the space rocks impact the Red Planet's surface will depend on their composition. If they are structurally unstable, they will probably explode or burn up in the thin Martian atmosphere, the study authors said. But if they're solid enough, they will leave a substantial impact crater.

It's important for scientists to be aware of the potential for missions like DART to launch more debris into space, the study cautions. Most of the asteroids that researchers will want to course-correct will be close to Earth. Many, including Dimorphos, will be "rubble pile" asteroids — loose accumulations of boulders like those liberated by the DART test. To truly protect our planet, scientists will need to be able to predict the number and trajectory of such debris before launching a DART-like planetary defense mission closer to home.

"If you put into space more stuff that can impact the Earth, then it's going to be a problem," Fenucci told National Geographic.

Fortunately, this problem is only hypothetical for now. Astronomers follow the orbits of more than 33,000 near-Earth asteroids, and have found that none of them pose a risk of hitting our planet for at least the next century.