Things just keep getting worse for Boris Johnson. On the same day that one of his MPs defected to the Labour party, former Brexit minister David Davis stood up in parliament to call for Johnson’s resignation.

The voices calling for the prime minister’s departure are mounting. If 54 letters of no-confidence in him are sent to the backbench 1922 Committee, a leadership contest will be triggered. Many members of Johnson’s party will therefore be calculating whether such a move against him is the right course of action. Central to this thinking will be whether continuing with Johnson as leader would cost them their seat in the next election.

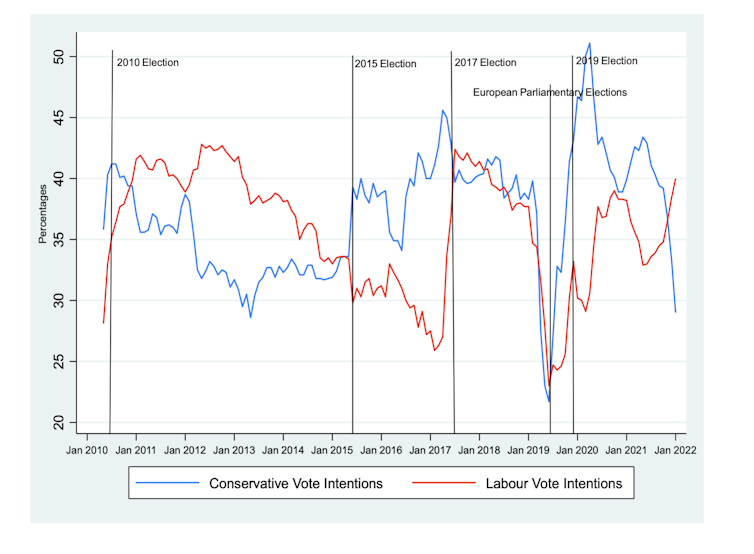

Support for the Conservatives has been nosediving in the polls following the scandal over gatherings held in Downing Street during pandemic lockdowns. We can learn something about how concerned Conservative MPs should be by looking at polling over the last ten years or so – specifically the voting intentions for Labour and the Conservatives since the general election of 2010.

Voting Intentions for Labour and the Conservatives, 2010-22

Not surprisingly general elections have a big impact on support for the two major parties. The Conservatives were boosted by Labour’s defeat in 2010, although they did not get an overall majority in that election.

Again in 2015, support for the party increased during the run-up to the election, but on this occasion David Cameron did win an overall majority – largely by decimating the voter base of the Conservatives’ coalition partner, the Liberal Democrats. Boris Johnson did very much better than his predecessors when he faced his own election in December 2019. He moved well ahead of Labour in the polls to win an 80-seat majority in the House of Commons.

However, the more striking feature in the chart is the effect of the European parliamentary elections of May 2019, near the end of Theresa May’s premiership. It produced a massive loss of support for both of the two main parties. Their popularity ratings fell dramatically from the start of that year and the outcome was grim for both.

Labour came third and lost ten seats and the Conservatives came fifth and lost 15 seats. Of course the last European parliamentary elections were not as important as general elections and the turnout was low. That said, support for the two major parties collapsed on that occasion.

The outcome of the European elections was a direct product of the turmoil and polarisation caused by Brexit, both in parliament and in the country. This crisis was triggered in turn by the loss of the Conservative majority in the 2017 general election. That election was the clear exception to the pattern of Conservative leaders improving their performance in relation to seats won in the House of Commons since 2010. The conclusion from the 2019 European election results is that major political crises have large effects on polling support and voting.

This is relevant to the present situation since the plunging support for the Conservatives in recent polls is comparable to that which occurred in the European parliamentary elections. In June 2019, the month after those elections, voting intentions for Theresa May’s party hit 22%. In the most recent YouGov poll completed on January 13 2022, the Conservatives received 29%. Since the turn of the year the party’s support has fallen like a stone.

However, there is an important difference between support for the two major parties in the run-up to the European parliamentary elections and at the present time. In 2019 Labour’s voting intentions fell as sharply as the Conservatives, whereas now it is rising rather rapidly. The recent YouGov poll put the party on 40% in vote intentions.

The government may have made “partygate” even worse in its attempts at damage limitation. Downing Street has embarked on what has been referred to as the “red meat” strategy.

This involves announcing right-wing populist policies such as attacks on the BBC, restrictions on the right to protest and hints that the Royal Navy will be used to deal with illegal immigration across the channel. In each case, the aim is to appease angry backbench MPs and distract the voting public. The calculation is that this may be enough to keep Johnson in Downing Street until the media frenzy moves on.

The problem with this strategy is that it is trashing the Tory brand among the large numbers of voters who are not attracted by right-wing populism. This is likely to reinforce the view among this group that Johnson is not fit to govern. They will be very difficult to woo back into supporting the party if he stays in after the media storm has subsided. A sharp move to the right, possibly followed by an equally sharp move to the centre (where most voters are located) once the storm subsides is likely to weaken the government’s credibility even more.

If Johnson is not replaced by a new leader, backbench Conservative MPs would be well advised to start brushing up their CVs in preparation for life after Westminster.

What did you think of this article?

Great | Good | Meh | Weak

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.