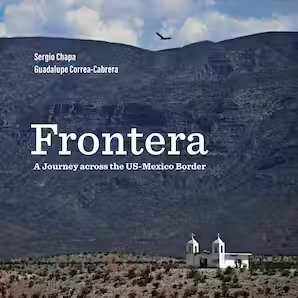

Sergio Chapa’s photos and a portion of this text also appear in Frontera: A Journey Across the US-Mexico Border and are reprinted with permission from TCU Press.

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera and I met when she was a political science professor at the University of Texas at Brownsville. She was studying drug cartel violence in the war-torn Mexican border state of Tamaulipas, and I was covering the same topic as a journalist for KGBT-TV in the Rio Grande Valley. We bonded over our work—and our mutual desire to “see the entire border.”

We made our first border-to-border journey together in June 2013, stopping at each crossing between Brownsville and El Paso with jaunts into Mexico. And we kept on traveling together for much of the next decade pursuing a dream that became our book, Frontera: A Journey Across the US-Mexico Border (TCU Press, January 2024).

In our first days on the road in June 2013, we’d seen closed businesses and other bleak effects of cartel violence on Mexican border towns, before rolling into Big Bend National Park. We had heard about the park’s beauty but marveled over its mountains, colorful canyons, and unique micro-ecosystems.

While driving along a rocky and mountainous stretch of the park, the Bible verse of Luke 19:40 sprang to mind, “I tell you, if they were to keep silent, the stones would cry out.” The original verse had a distinct meaning, but for us, it meant that if we failed to acknowledge the beauty before our eyes, the rocks themselves might literally protest. After a few minutes, we shrugged it off as maybe stupor over the 90-degree-Fahrenheit day or exhaustion from the eight-hour drive.

But after settling into our hotel in Terlingua, we joined other guests for dinner and live music on a rooftop patio where monsoon rains and lightning strikes could be seen in the distance. A couple of beers later, a solo guitarist sang these lyrics: “And the rocks will cry out.” We looked at each other wide-eyed in that moment of serendipity. After his set ended, we spoke to the musician, who told a story similar to our own.

That night, we sat outside until millions of stars appeared, tracing the Milky Way above us. It was one of what we called momentos mágicos along the frontera.

The U.S.-Mexico border … is also a land of contrast—austere landscapes and lush oases; thunderstorms and rainbows; robust industries and ghost towns; great wealth and aching poverty.

Despite the negative political rhetoric, the U.S.-Mexico border is a beautiful place, home to welcoming and warm people. It is also a land of contrast—austere landscapes and lush oases; thunderstorms and rainbows; robust industries and ghost towns; great wealth and aching poverty. The residents, known as borderlanders or fronterizos, are among the poorest in the United States. Those in Mexico inhabit cities that can be very unsafe. Nonetheless, these citizens often open their homes and pocketbooks to help stranded tourists as well as asylum seekers from Central America, South America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia.

Over the last decade, we have traveled different segments and made three different trips along the whole frontier, from Brownsville, Texas/Matamoros, Tamaulipas, to San Diego, California/Tijuana, Baja California. When we started, we were fronterizos, living and working in the Rio Grande Valley region. We still understand border dynamics, though we’ve both moved; I’m now a freelance writer and energy industry analyst in Houston and Correa-Cabrera teaches at a university in Fairfax, Virginia.

The border region is home to billions of dollars in trade and beautiful landscapes, including beaches, dense subtropical forests, deserts, and mountains. Its sprawling cities offer disparities of their own, with industrial parks and fashionable shopping malls, as well as immaculate country clubs and neglected colonias, where some earn a meager living scavenging recyclable items from landfills.

Its international boundaries were established by wars but people with family, friends, and businesses on both sides have often ignored dividing lines. Far from the capitals of Washington, D.C. and Mexico City, they created their own culture, which is distinct from their parent cultures. The result is a mixture where “Spanglish” has become its own language and where the music, food, binational economy, and resilience of the people reflect this bicultural blend.

Many books have been written about the U.S.-Mexico border, but none is like ours. Frontera offers a glimpse into every crossing community in all U.S.-Mexico border states. It includes notes and reflections by experts, academics and others about the border and about how the pandemic has changed places we visited—and thought we knew so well.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the partial closure of the U.S.-Mexico border transformed the region’s face and socioeconomic configuration. Although we do not know what the borderlands will look like in the future, we do know the border and fronterizos will quickly adapt.

We do not know what the borderlands will look like in the future, we do know the border and fronterizos will quickly adapt.

Our last trip to complete this book took place in July 2021.

There was no cloud in the sky on that 100-degree day as we drove Mexico’s Federal Highway 3 between the resort town of Puerto Peñasco, Sonora, and the border city of San Luis Río Colorado.

Neither of us had ever before visited this desolate desert highway along the Gulf of California, but we’d been warned: There is no cell phone service on the remote road, where numerous robberies had taken place and suspects had left victims stranded.

We were traveling in a pack of cars, so things seemed safe at first. I dodged dozens of potholes and drove around dunes slowly creeping over the highway.

We were amazed by views that few Americans ever see: Dunes, crystal blue water, and rugged canyons stretched out beside the highway. The finish line that day was supposed to be dinner with friends in Tijuana.

But then, I couldn’t avoid a deep pothole in time. The impact sent my front passenger side tire flying into sand. Luckily, I was able to stop the car without any other damage. I saw that the side of the tire had split in half. It was unbearably hot and, as predicted, we had no signal.

That’s when an old, beat-up car pulled up behind us. We couldn’t see the driver inside, and suddenly, those warnings flooded back. Panic briefly overcame us until we saw a man get out of the car with his wife and 6-year-old son.

He didn’t waste any time. He had a spare tire, which wasn’t really the right size, but we somehow made it fit. He waited until we were sure the tire would work and refused any money. We made it to Yuma, Arizona where we got a proper-sized tire. We didn’t get that man’s name or number, but he saved our lives. He was our “border angel.”

We are forever grateful to that anonymous and humble Good Samaritan, who helped us tell the true story of the border. I still keep the spare tire he gave us in my trunk, ready for the next person who needs it.