Owen Marshall on a brilliant novel set at Tekapo

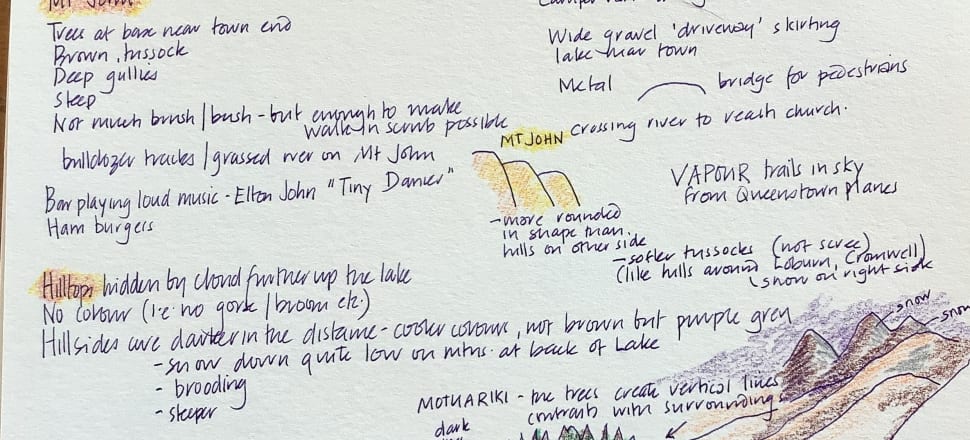

Laurence Fearnley's new novel Winter Time has two major strengths, and the first of these is the setting. Most of the story takes place in the South Island's Mackenzie Country, at the lake and village she names Matariki, but which are based on a clearly recognisable Tekapo. She has set other work in the region and her allegiance to it is plain.

Her evocation of the snow country is convincing and compelling, drawn from personal experience. Fearnley has talked of her upbringing in a family of trampers and campers in this country, a love of bird watching and natural vegetation, and her descriptions ring true: "The driveway was distinguishable from the road only because of the gateposts at its end. Otherwise it was a smooth blanket of white, glittering where patches of sunlight caught it. His shoes sank down, making soft, rounded prints. Snow stuck to his socks and the hem of his trousers, building up in a thick layer that stiffened and froze as he walked. His weren't the only tracks. Some animal, probably a cat, had cut a trail across the garden , leaving paw prints that disappeared at the hedge and reappeared metres away towards the old barbecue area."

Not only is this setting authentic, it mirrors the emotional state of the novel's protagonist, a physical and visual complement to the emotional condition experienced by Roland March, the character whose creation is the second strength of the novel. Roland's winter is not so much one of discontent, but rather sorrow, loneliness and unease. Brought up in Matariki, but never comfortable in the rural lifestyle, he moved to Sydney after an unproductive stint at university, to run a wholefoods store with his partner Leon.

Misfortune has stalked his family – his father despised him and abandoned them, his loved mother died after a long, savage illness, his sister Casey died early, brother Isaac went missing, presumably drowned. Further tragedy marks the opening of the novel when Eddie, Roland's only surviving sibling, and one he loved despite little contact in recent years, drowns after he loses control of his ute and it plunges into the hydro canal. Roland returns home to deal with all the issues arising, including the fate of the family home.

His relationship with Leon deteriorates. He has little emotional support apart from Bay, a woman friend of Eddie's. Roland's time in Matariki is made more difficult, even threatening, because someone purporting to be him spreads rumours on line of something suspicious in Eddie's death and makes accusations against Roland himself.

Roland is in his homeland, but he had never been at ease there and all his family are dead. He is alone and his emotional desolation seems reflected in the bleakness of the season. A classmate describes him, "You're weak and won't take responsibility for your life, because you're scared of losing what you have. You're scared of being unloved and you think you are unlovable."

Roland has his virtues. although he's a sad figure in many ways, without much charisma, and often indecisive. But he's such a well-drawn and complex character, with a longing for acceptance and understanding, that our sympathy is engaged. It's a challenge for a woman writer to create such a protagonist, one who carries so much of the novel's weight, and Fearnley has succeeded admirably.

She's an experienced and accomplished writer with a command of language that allows her to cope with the considerable demands her highly personal writing imposes. Her skills are well displayed here, especially in her descriptions of the environment and personal relationships. The occasional move from third person narration to first person for the same character I found distracting rather than profitable, and I think the novel would benefit from some crisping. The fullness of description and explanation that the novel permits is one of its merits and authentic detail rather than generality adds to a sense of coherence and context in writing, but momentum is important in works of length. Fearnley is adept at creating dense prose, so much so that sometimes it becomes an indulgence and the urgency of the narrative falters as digression breeds digression and flashbacks mount.

But the novel is a success, most obviously because it captures people and place – a place of scents and colours, warmth and cold, wind, trees and birds, sounds, rocks and water, the houses of the people who live there: "At this time of year, the last of the evening sun lacked any hint of warmth. The sunset was not golden, or rose coloured, but rather a cold violet that became greenish yellow before fading to a blue-grey. Colour drained from the sky, the hills surrounding the lake fell into shadow, but then, as if to reward the watcher, a thin beam of sunshine sparked up the slopes for a few brief minutes."

Winter Time is meaningful and challenging, with much unresolved. It's a brave story, and well told. There's a sincerity in all of Laurence Fearnley's work that gives it a special weight and character.

Winter Time by Laurence Fearnley (Penguin Random House, $36) is available in bookstores nationwide.