Back in February, with Super Bowl LVII only days away, Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie reclined in an oversize chair inside the offensive line meeting room of a conference rival. A knowing smile spread wide across his face, and his eyes danced at the possibilities on the horizons near and far.

Before and after Philadelphia conducted one of its final practices at the headquarters of the Cardinals in Glendale, Ariz., Lurie attempted to explain how the Eagles arrived at that point in the franchise’s decorated history. It began with the philosophy he shared, developed, tweaked and followed with his general manager, Howie Roseman. And that philosophy started a choice that might sound simple—to take risks that make sense, regardless of perception—but rarely is easy. Most NFL franchises say they embrace this ethos. But only a handful of teams, such as the Eagles, truly do.

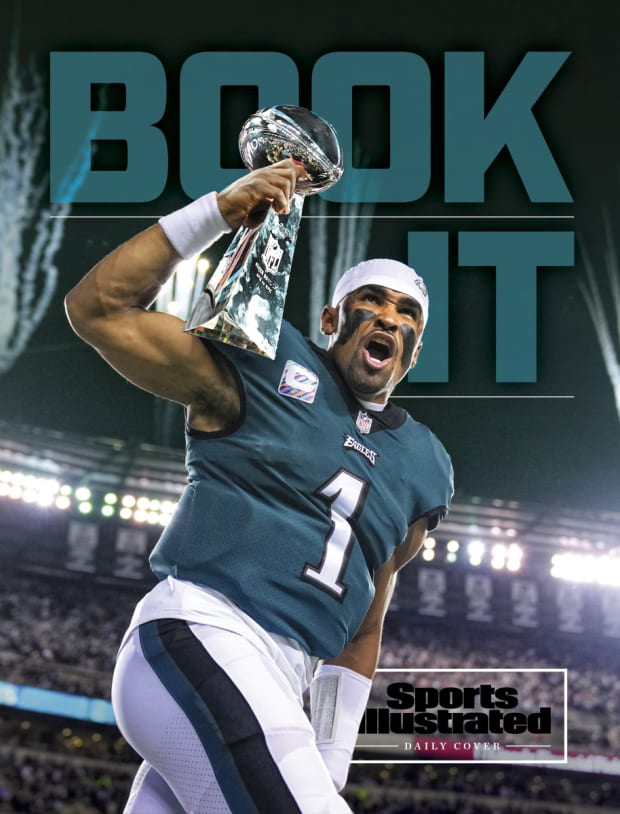

Photo Illustration by Dan Larkin; Mitchell Leff/Getty Images (Hurts); Katelyn Mulcahy/Getty Images (Lombardi Trophy)

One question, in two separate interviews that stretched for more than an hour, momentarily stopped Lurie. What actually scares you? He paused, leaned back, considered. “I’ve never been asked that,” he said after 10 seconds or so, buying time. Then he said, “The thing that would scare me the most is: to do the expected. Doing the ‘traditional thing’ would scare me. Realizing we’ve morphed into that approach, whether in player personnel or picking coaches or offensive strategy. That’s a fear of mine. I’m always on the lookout for that. Are we getting too conservative in some way?”

The answer—in Lurie’s tenure, in recent seasons, for the overhaul, before the Super Bowl and after losing to the Chiefs—never changed. In terms of conservative leanings, the Eagles are the NFL equivalent of a nudist colony, which is to say they aren’t conservative at all.

When Lurie purchased the franchise in 1994, he paid Norman Braman a full $195 million. He understood two important things: This was a big-market team with all sorts of potential—and Braman was about as popular as the Giants with Philly football fans. Lurie resolved to take the approach he would, nearly three decades later, summarize in one word: fearless.

As the rare sports owner with a stout IMDb page, not to mention three Academy Awards, Lurie set out to tell another story, that of a professional football franchise back on the rise. Sure, the Eagles had amassed all of four playoff appearances—never advancing beyond the divisional round—in the previous 12 seasons. He was there to change that and, by extension, the narrative. “How should you operate a sports franchise?” he asked that afternoon in Arizona. “That’s the story.”

The question now, after a large chunk of the NFL offseason—after the initial wave of free agency, the draft and doling out the richest contract by some measures in league history—is even more ambitious. Does this story end with a championship next February?

David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated

The Eagles entered the 2023 offseason like most franchises that lose a Super Bowl. They were driven and motivated, but they would have been, anyway. They were set at head coach (Nick Sirianni), GM (Roseman) and quarterback (Jalen Hurts). But Hurts needed a new contract, or they risked losing him altogether. Several prominent veterans were considering retirement (again), and their success meant overpayments from other teams to their free agents.

Did the Eagles fear these months would make them worse? Of course not.

Instead, Roseman ignored the fan base that lauded and hated him and sometimes both on the same day. Never mind the Birds fanatics who flipped him the, well, bird, the incensed sports radio callers, or the Super Bowl the Eagles seemed poised to win until they lost, late, to the otherworldly force known as Patrick Mahomes. Roseman even possessed more draft capital than normal.

First, free agency beckoned. This marked the greatest unknown in Roseman’s latest reconfiguration. But March unfolded in close-to-ideal fashion.

In seven days, three cornerstones—defensive end Brandon Graham, center Jason Kelce and defensive tackle Fletcher Cox—all chose to embark on another run over retirement. The Eagles also re-signed several important players: Lane Johnson, whom Roseman called “maybe the best right tackle in NFL history” last February; cornerback Darius Slay, who told reporters he took less money to remain in Philadelphia; corner James Bradberry, who had an All-Pro 2022 season and the overblown LVII criticism; and running back Boston Scott. Roseman even added pieces: another back (Rashaad Penny) for depth, two safeties (Terrell Edmunds, Justin Evans) to shore up the defensive backfield, and an above-average backup quarterback (Marcus Mariota) and a cornerback whose first name embodied their approach (Greedy Williams).

All the new signees inked one-year deals, which gave Roseman flexibility in future seasons and the ability to finalize the contract that mattered most. The general manager, as he said in February, spent last offseason building around Hurts, intent on maximizing the quarterback’s existing gifts and fully evaluating whether Hurts should command record money. Hurts answered any lingering questions early into last season. He became a league MVP candidate before a December injury sidelined him for most of the final month, came back, played hurt, played well and nearly won Super Bowl MVP honors. Now, Roseman sought not to maximize Hurts’s talent alone; now, he needed to remove the “near” before “champions.”

Mitchell Leff/Getty Images

They started with Hurts’s extension. That it would happen, this spring, was never in doubt. They settled on five years and up to $255 million, with a signing bonus of roughly $23 million and $110 million guaranteed the second Hurts scribbled his most important autograph. The average annual salary—$51 million—briefly marked an NFL record before Lamar Jackson eclipsed it by $1 million a year. As other quarterbacks sign new deals in the same neighborhood, Hurts’s extension will become more of a bargain (relative) with each subsequent quarterback contract.

That left the draft for Roseman to continue his nonextreme (but significant) makeover. He traded up one slot, to No. 9, to snag defensive tackle Jalen Carter, then selected his college teammate at Georgia, linebacker–pass rusher Nolan Smith, at No. 30. Both “fell” relative to predraft expectations, adding theoretical value to the haul. Carter, who pleaded no contest in March to reckless driving and racing for his involvement in a fatal car crash, landed in an ideal incubator, with two elder statesmen in Graham and Cox as mentors.

This strategy was, apparently, not coincidental. The Athletic ran an amusing anecdote about Roseman returning from a practice at Georgia and, when Sirianni asked who he liked, responded with, I don’t know, like, the whole defense. This conversation happened after the Eagles used two of their first three selections last year on Bulldogs (defensive tackle Jordan Davis, linebacker Nakobe Dean) and before Philadelphia snagged both first-rounders and their teammate, cornerback Kelee Ringo, in Round 4 last weekend. Ringo’s pick-six cemented Georgia’s triumph in the 2022 national championship game. And Roseman, Mr. Georgia on His Mind, still wasn’t done! He also dealt for Lions RB (and UGA alum) D’Andre Swift, a young, feature back to add to Sirianni’s arsenal on offense. The cost: two measly late-round picks.

Now the only thing left for the Eagles is what those Bulldogs did the past two seasons. Win championships. Nothing else matters.

Rich Graessle/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

What does all this say about the Eagles? Roseman answered that question at the team’s hotel during Super Bowl week. “The league is set up for parity,” he said. “It’s set up for teams to go 7–10, 8–9. And to break out of that, you have to take some risks that give you a chance to be really good but also to fall on your face.”

Since winning the Philly Special Super Bowl in early 2018, the Eagles have embodied their stated philosophy more than ever. They have fallen on their collective face (like in ’20). They have been really good (last season) and expect to be again (this fall).

Consider just the past five seasons. The Eagles made the playoffs in 2018 and ’19, but those appearances failed to mask the obvious: They were headed in the wrong direction. They bottomed out in ’20, finishing 4–11-1, dead last in the NFC East, while resting stars in their meaningless finale against the Giants, drawing a rebuke about respecting the game from the opposing coach, Joe Judge. Soon, they would fire the coach, Doug Pederson, with whom they won a Super Bowl three seasons earlier.

Philadelphia hired a young-but-unproven offensive wizard in Sirianni to replace Pederson. Sirianni was undoubtedly a risk—and long before a fairly disastrous introductory press conference stoked angst amongst the ever-reasonable Eagles fan base. He showed up to Lurie’s mansion for the job interview in a rented minivan. That meeting was possible only because Sirianni happened to be in the area, on a family vacation, hence the wheels. He didn’t hesitate to pace Lurie and Roseman through demonstrations, turning Lurie’s living room into a practice field and two executives into football prospects. They were comfortable, that day, with any “risk” in hiring Sirianni. “At the time, my judgment was we had plateaued or were descending to some degree,” Lurie said in February, while lauding Pederson in general as a coach. “Was it stale? I don’t know. I don’t want to say that. But I determined we needed a different coach.”

It's funny, this whole risk thing. Hiring Pederson elicited much negative feedback. Parting with him—after the triumph—incited more of the same. The philosophy itself didn’t change, in either instance. The Eagles made decisions they believed would lead to Super Bowls—drafting Hurts in the second round, despite the massive extension paid to Carson Wentz; shipping Wentz out after 2020—not playoff appearances. Lurie became only the fourth NFL owner to hire three different head coaches who reached the Super Bowl, as Sirianni joined Pederson and Andy Reid.

The Eagles view their decision-making calculus for hiring head coaches as a competitive advantage. So much so that Roseman, when asked what he would pose to Lurie in an interview the next day in Arizona, said, “What’s your secret to hiring great head coaches?” Roseman paused, then cackled. “Then say, Howie says, don’t say anything!” Indeed, Lurie answered every question but that one.

Perhaps that’s because Lurie built an organization that, in many important ways, echoed his greatest sports influences: the Boston Celtics of his childhood and the first person he met with after becoming an NFL owner, the late Bill Walsh. The famed coach was at Stanford when Lurie visited to discuss organizational philosophy. Define it, Walsh told him. Then take risks that make sense, regardless of perception. “Being fearless,” Lurie said again. “Not worrying about outside opinions or unpopular decisions, because those don’t correlate with winning.”

Several weeks ago, the Eagles, philosophical bent solidified, brilliance proved once more, were considered a co-conference favorite with the 49ers. Somehow, oddsmakers at one point dropped Philadelphia slightly behind San Francisco. Perhaps that owed to the Niners signing talented defensive tackle Javon Hargrave in free agency, stealing him from the Eagles. But Hargrave’s price tag (up to $84 million over four seasons, with $40 million guaranteed), age (30) and the Carter selection made losing him an acceptable risk for Philly’s brass.

There’s not another explanation that makes sense. The Eagles should be favored to win the conference, if not the Lombardi Trophy. Their most significant departure after Hargrave was cornerback C.J. Gardner-Johnson, and they addressed that position and their corner depth in both free agency and the draft. San Francisco, meanwhile, waved goodbye to its starting right tackle, a starting linebacker, two pass rushers and its slot cornerback. Philly had the better draft—a “master class,” according to NFL.com. The Eagles have the better quarterback. They had a better season last year, and it featured an NFC championship game stomping of … the 49ers.

All of which leads to an (inevitable?) conclusion: Philadelphia Eagles, champions of Super Bowl LVIII next February. Book it.