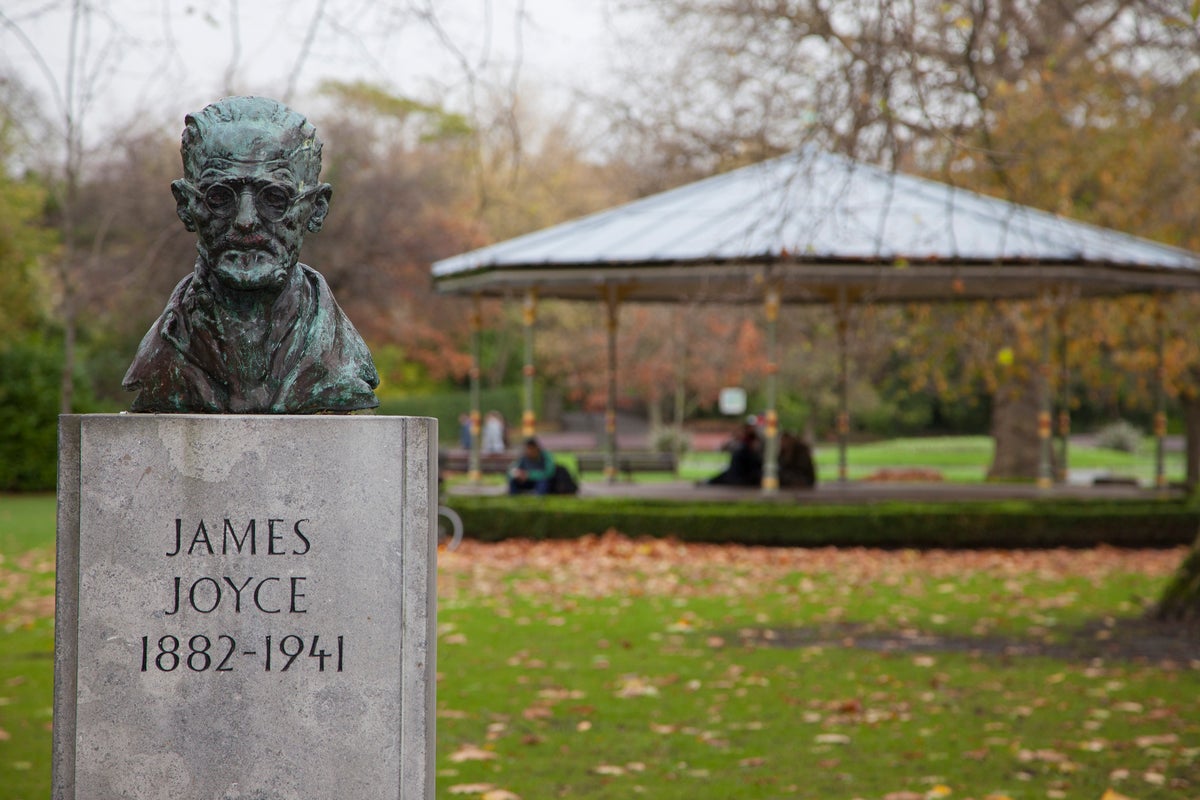

This year marks 80 years since the death of the great Irish writer James Joyce (1882-1941). His most famous novel, Ulysses (1922), is one of those books, like Moby-Dick or Infinite Jest, that more people begin than finish. The tome is widely believed to be a stream of consciousness novel and you could certainly be forgiven for thinking that, if, like many, you only made it 100 pages or so in.

I often advise against starting at the beginning of the novel. In the case of Ulysses, you are thrown head-first into the difficult stream of consciousness of Stephen Dedalus, a precocious 22-year-old writer. The fourth chapter, instead, is a much more accessible opening. It too offers a stream of consciousness, but an easier sort, belonging to the novel’s other main character, Leopold Bloom, a hapless but loveable 38-year-old advertising canvasser. On the day the novel is set, 16 June 1904, Stephen and Bloom strike up an unlikely friendship in Dublin. To read Bloom’s thoughts is to be taken into a world of sensations, trivia, and wonder.

However, venture further and you’ll discover that Ulysses morphs, becoming instead a great anti-stream-of-consciousness novel.

Bergson’s stream of consciousness

For French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941), our stream of consciousness is our continuous sense of time, in which past, present and future merge. It is the fluid life at the heart of our identity. According to Bergson, these streams are at the centre of every object and every person.

Bergson believed we can either “analyse” or “intuit” things or people. When we “analyse” something, we remain outside its stream. We superimpose on its fluid life our own static symbols, like language. Using words means “we do not see the actual things themselves”, just “the labels attached to them”.

Another example is numbers. We impose minutes and hours on fluid life. For instance, you can “analyse” a day, breaking it into 24 hours. But to “intuit” it, to see it from within the stream, is to see that time is not so rigid or easily quantifiable – it moves slower when you’re bored, and faster when you’re having fun.

In our workaday lives, “analysis” is a necessary shortcut. We need words and numbers, labels and time, to get things done. Artists, however, according to Bergson, have the gift of intuition.

For example, authors’ imaginative use of language makes words a gateway to the streams at the heart of life, rather than distracting labels imposed upon it. Borrowing such ideas, literary critics posited that the stream-of-consciousness novelist is one who can “intuit” the stream of consciousness of characters and so become them.

Just as Joyce’s characters can’t intuit streams of consciousness, nor can he. He knows that static literary words can’t account for the fluidity of our interiors

Joyce tries for a moment, becomes his characters, but soon gets bored with Stephen and Bloom’s streams of consciousness. By the seventh chapter, he begins a long firework display of other styles. From here on, Stephen and Bloom’s streams of consciousness are elbowed out of the way by newspaper headlines, expressionist drama and even romantic fiction. Or they’re shushed by a scientific manual or an encyclopedia of English prose styles.

Joyce fails to find the stream

So Ulysses is a much less consistent stream-of-consciousness novel than many. But it’s also an anti-stream-of-consciousness novel, as Joyce comically demonstrates both his and his characters’ failure to intuit streams.

Joyce enjoys showing us that people are mechanically absent-minded, often because language itself is a mechanism which gets in the way of our efforts to intuit fluid reality.

For example, Stephen, though a creative writer, isn’t at all intuitive. All he can see are the labels attached to things, albeit highly literary labels. When he sees a dog on the beach, his love of words conjures a horse, a hare, a calf, a bear, a wolf, a leopard, a panther and a stag. He can’t focus on the dog.

Bloom’s mechanical behaviour is less literary (words) and more scientific (numbers). True, he is better at intuiting his cat than Stephen is the dog: “Wonder what I look like to her?” he muses, trying to intuit himself into her stream of consciousness. But soon his mind turns to numbers: “Height of a tower? No, she can jump me.” Here he reverts to analysis as he strains to make sense of their difference in height using his human scale, not the cat’s.

Just as Joyce’s characters can’t intuit streams of consciousness, nor can he. He knows that static, literary words can’t account for the fluidity of our interiors. Every time he reaches for a new style, in each new chapter, he acknowledges these failures and moves on with glee to the next.

A stream of consciousness does dominate the last chapter. Here we tune into Bloom’s wife Molly’s stream and hear about her afternoon of sex with a colleague. Is this the stream we have been waiting for? Yes and no.

Molly’s thoughts do flow through past, present and future, uninterrupted and unpunctuated. But the Molly we get to know, while charismatic, is something of a static symbol herself: the stock character of the sexually frustrated wife. As we reflect on 80 years since Joyce’s death, Ulysses reminds us that consciousness will always elude the novel – but that really, that’s where the fun lies.

John Scholar is a lecturer in the Department of English Literature at the University of Reading. This article first appeared on The Conversation.