In the early 1990’s, Manic Street Preachers exploded onto the music scene in a mess of eyeliner, leopard-print and loud-mouthed punk rock attitude. The Blackwood quartet were a giddy fusion of glam rock excess, erudite bookishness and uncompromising, anarchic, political polemic. If Andy Warhol had picked four blokes from a miners' strike picket line and tried to turn them into The Clash, they’d be Manic Street Preachers.

The group's first two albums, 1991’s Generation Terrorists, and 1993’s Gold Against the Soul, had made them infamous rather than famous. Their attention-grabbing quotes and media-baiting behaviour, most notably guitarist/band architect Richey Edwards carving '4 Real' into his arm during a heated conversation with NME journalist [and future Radio 1/6Music DJ] Steve Lamacq, gained them plenty of column inches in Britain's weekly music press, and a rabid cult fanbase, but the fact that their biggest UK chart hit prior to 1994 was a cover of Suicide Is Painless (Theme From MASH) was an indication that they hadn't yet captured the imagination of mainstream music fans.

When the band began work on their third album at the start of 1994, all was not well within their camp. Drummer Sean Moore recalls that the Manics believed they had been “going a bit astray” with the cleaner, more Americanised sound of Gold Against the Soul, and a conscious decision was made to lean back into their more stripped-back British influences, artists such as Magazine, PIL, Gang of Four and Joy Division.

There was also Richey Edwards' condition to worry about. The guitarist was no musician - proudly barely able to tune his own instrument - but he exuded undeniable star quality. His film star looks, brilliantly eloquent interviews and aesthetic command of the band made him their focal point, and, much like Nirvana's Kurt Cobain, he'd become a beacon for angry, confused and troubled young people. Outwardly, the toll this near-Messianic status took on the guitarist was all too evident, as he struggled with anorexia and self-harm, topics he was typically open and candid about in interviews.

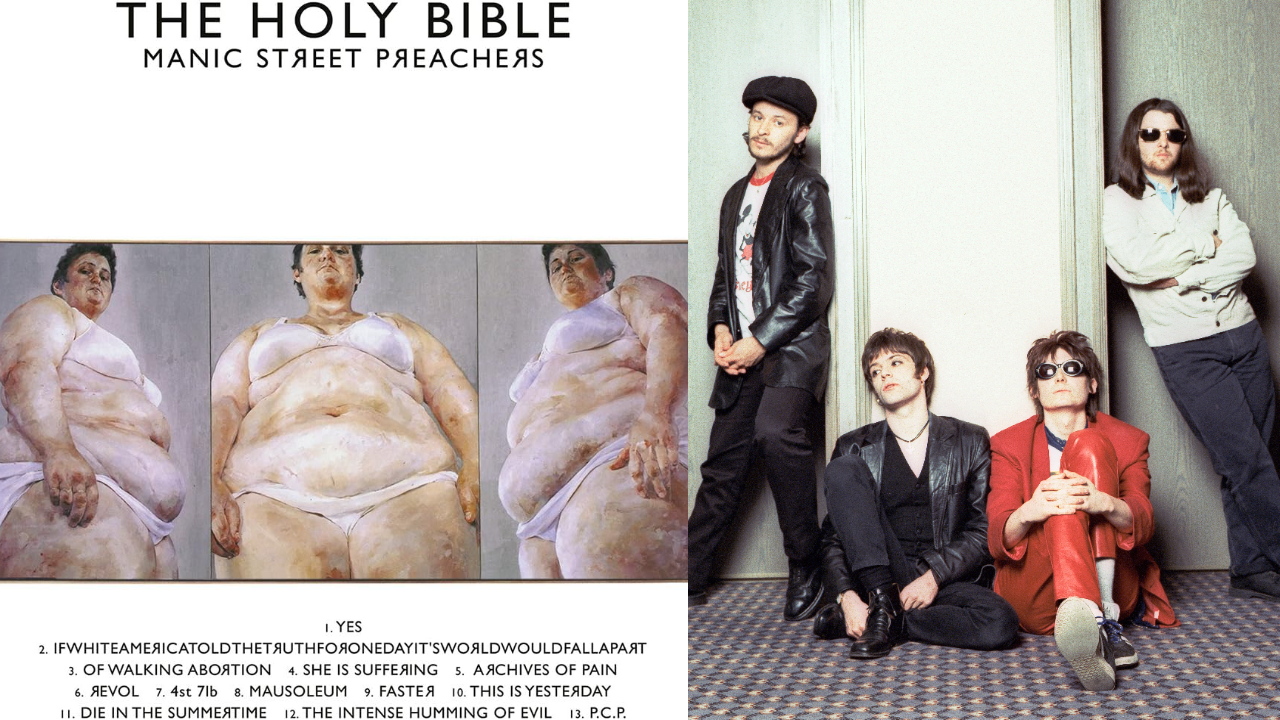

These were the factors that helped shape one of the darkest, bleakest albums in the history of rock music: The Holy Bible.

The recording, release and aftermath of The Holy Bible has passed into Manic Street Preachers lore at this point.

People still talk about their switch to rough, angular post-punk, their aesthetic adoption of grubby, stained military wear, the infamously gruelling tour of Thailand (where Edwards was treated as some kind of deity by fans and his self-harm escalated to shocking levels), and the iconic Top Of The Pops performance of Faster which found frontman James Dean Bradfield wearing a black balaclava, and inspiring a record number of complaints.

Fans also recall in awed terms the group's final gigs with Richey Edwards, a trio of December 1994 shows at London’s [now demolished] Astoria Theatre, where the sound was so extreme that the band members got nosebleeds onstage, leading them to destroy all their gear at the close of the final night. "If only one band is going to mean the world to you, it should be them", NME's review of that show concluded.

Then, of course, there was the guitarist's disappearance from a London hotel on February 1, 1995, on the eve of a scheduled US promo tour, and the confusion, sadness and unwelcome speculation which followed.

Though the album peaked at number 6 on the UK album chart, and didn't trouble the Billboard 200 at all, few records that have come in its wake have as wild a narrative surrounding it. The question is: 30 years on, with its legacy firmly established and the story so familiar to so many, does The Holy Bible still have the potency and power of its reputation?

Listening back to The Holy Bible today, as well as poring over pictures, interviews and live performances from the time, it’s quite incredible to see just how revolutionary, shocking, thrilling and transgressive it remains.

Firstly, viewed from an era where a band 'reinventing' themselves often equates to nothing more than bleaching their hair, doing a song with Ed Sheeran or making their music a bit more poppy, Manic Street Preachers' sonic and visual evolution is a revelation. Transitioning from looking like a Poundstretcher Guns N' Roses to an insurrectionist guerilla cell is one thing, but to go from the fizzy, arena-tilting glam-punk of Generation... and the radio-friendly sheen of Gold... to the harsh, difficult noise of The Holy Bible feels like even more of a risk now than it would have in 1994.

The main reason why The Holy Bible still retains such power is Richey Edwards. It’s hard to think of many, if any, pieces of music that detail the very worst aspects of humanity in such stark and unflinching detail as Edwards does here. His lyrics wildly swing from selfish and scathing to pain, regret, self-loathing and isolation in the most shocking way.

Yes opens the album by graphically and nonchalantly talking about castrating and having sex with an infant. In isolation it seems like something even Cannibal Corpse would draw the line at, but, far from being written for shock value, Edwards is commentating on how all humans are born to be prostituted to the point of stripping them of all humanity. It’s a heavy, complex subject, unflinchingly dealt with.

At times The Holy Bible remains a struggle to listen to. Archives of Pain's obsession with serial killers and its seemingly pro-capital punishment message is deeply uncomfortable to sit through. Mausoleum and The Intense Humming of Evil were inspired by visits to Nazi concentration camps in Dachau and Belsen, yet both seem disconnected and emotionless towards The Holocaust. Of Walking Abortion has been described as Edwards mentally role-playing as a fascist dictator.

Despite this, maybe because of it, this unflinching honesty gives these songs an undeniable power. Hearing things that should not be openly expressed, being expanded upon so fluently, is like sitting in on the confession of a deeply troubled and tortured man. It's as if Edwards admittance of his own base instincts is some kind of sonic self-flagellation.

If those songs retain their shock value, in the moments where Edwards opens up about his unsettling mental and physical health, The Holy Bible veers from hard to heartbreaking. Die in the Summertime and This is Yesterday are both crushing laments to the passing of time, the former touching on the worthlessness that so many elderly people feel, while She is Suffering wearily fixates on how desire can destroy any sense of true happiness.

Perhaps the most shocking song on the album is the stark depiction of the mind of an anorexic on 4st 7lb. Lyrics such as “I want to be so skinny that I rot from view” and “such beautiful dignity in self-abuse" are genuinely traumatic to hear. The song is The Holy Bible in a nutshell: utterly bleak and hopeless, yet somehow beautiful and poignant, desperately uncomfortable to listen to, yet impossible to ignore.

Although it confused and alienated many upon release, the album, later added weight and context being the final word from Edwards, is now spoken about in the same reverential tones reserved as Joy Division’s Closer, Nirvana’s In Utero, and, more recently, Lil Peep’s Come Over When You’re Sober, records that gave more than a hint at the fragile state of mind of their creators, all of whom passed around the time their definitive statements were shared with the world.

Heartbroken as they were, and changed forever by their friend's disappearance, James Dean Bradfield, Nicky Wire and Sean Moore chose to carry on, ultimately achieving far greater commercial success than The Holy Bible could ever have given them. To celebrate its 20th anniversary, the trio dusted off their army fatigues and played The Holy Bible in full on tour, but it was quite awkward to see these now happy and content middle aged men trying to replicate something so visceral.

In 2024, listening to The Holy Bible is a reminder of how gripping and stimulating it is to hear an artist truly, utterly unafraid to fearlessly confront and embrace the depths of the ugliest and most distressing parts of society. It remains one of the heaviest, most unique, special and singular albums in history.