Life expectancy in Blackpool, in the north-west of England, is the lowest in the country: 5.3 years lower than the national average for men and 4.2 years lower than the national average for women.

Commenting on these stark health inequalities, former children’s commissioner for England Anne Longfield recently noted that healthy life expectancy for children in Blackpool was the same as for those living in Angola.

Children in the town are also struggling at school. In the 2022-2023 academic year, the average educational attainment rate (or highest level of education achieved) for students at state-run secondary schools in Blackpool hit a low of 34.9, down from 38 the previous year, and 40.9 in 2019-2020. Only Knowsley, in Merseyside, 50 miles to the south, scored lower, with 33.2.

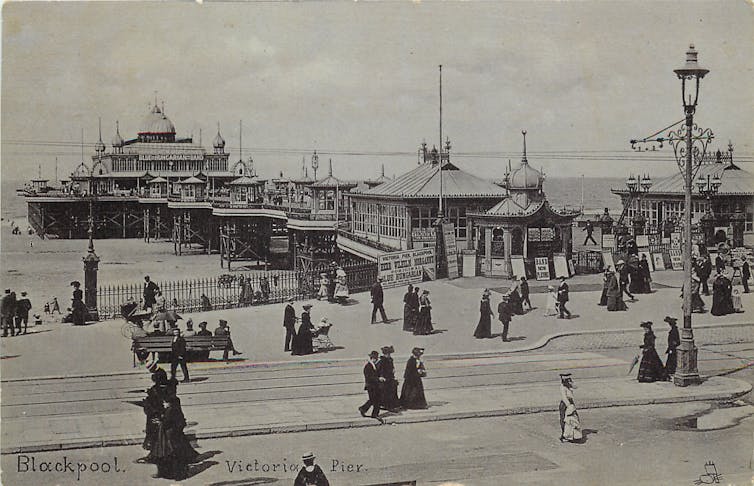

This is a far cry from the early 20th-century, when writer Thomas Luke declared Blackpool “one of the wonders of the world”. Quite how the thriving 1930s holiday destination on the Irish sea has become a struggling coastal community reflects wider societal shifts and economic challenges.

Our research shows that Blackpool is not unique. Many coastal communities across the UK face similar challenges.

Mid-century troubles

Blackpool sits on the edge of Lancashire, the county widely regarded as the cradle of the industrial revolution. The histories of both are firmly entwined.

Today 141,100 people call Blackpool home, the introduction of the railway in 1846, saw almost as many visitors – 100,000 people – spend their annual holiday there every year. They came from Lancashire and Scotland to enjoy the Pleasure Beach amusement park, the piers, the ground-breaking electric street illuminations.

By the eve of the second world war, its annual visitor count had risen 100 fold, to 10 million. From the late 1960s, however, things changed.

The introduction of cheap travel and package holidays to the Mediterranean, saw Blackpool, like all English coastal resorts with less reliable sunshine, fall out of favour as overnight holiday destinations.

In the 19th century, Blackpool had seen a boom in multi-occupancy housebuilding, in response to the demand for tourist accommodation. The slump in tourism numbers from the 1970s onwards now meant the town was left with an aging multi-occupancy housing infrastructure – expensive and difficult to maintain.

Today, Blackpool is the seventh most densely populated area in England outside of Greater London. The population is heavily concentrated in Blackpool’s inner area, a very dense and grey urban environment. It is characterised by guest houses, no longer required, which have been converted into rented bedsits and flats.

The local economy has suffered further from continued underinvestment in railway infrastructure by the government. This has made travel to Manchester and Liverpool and other cities difficult, resulting in fewer job opportunities for local residents.

The town has experienced large reductions in central-government funding for local services too. Between 2010 and 2017, core funding for Blackpool Council had the highest reduction out of any local authority in England. And these cuts were greater than in more affluent areas.

Our research has shown that reductions in government funding has contributed to stalling life expectancy across England.

Health outcomes in the area have suffered as a result, compounding the harms wrought by poor market conditions and a historic lack of infrastructure investment. The long-term sickness rate in Blackpool is 17% higher than the national average.

Local initiatives

But now Blackpool has secured £5 million from the National Institute of Health and Care Research. As part of this, the town has launched a new community research team. Local residents are employed and trained to co-design and deliver interventions to tackle some of the entrenched inequalities the town faces.

This has resulted in a Blackpool version of the family safeguarding model, “Blackpool Families Rock” which will come into practice in April 2024. Blackpool has the highest number of children in care in England. At a rate of 218 per 10,000 children in the local authority’s care, this represents more than three times the national average of 70 per 10,000.

Blackpool also has the highest rate of deaths from drugs misuse in England. So through a supported housing scheme, implemented in 2021, the town is now seeking to reduce the risk of homelessness for those recovering from substance misuse.

And to address high levels of young people leaving the town and unemployment, a Blackpool youth hub called The Platform was established in 2022. It supports young people aged 16-24 in developing skills and improving their chances of employment.

In his 2021 report, as England’s Chief Medical Officer, Christopher Whitty highlighted that many coastal communities across the UK face similar challenges, with worse health and economic outcomes than their inland neighbours. However, it does not need to be this way.

Places like Blackpool have huge potential. They boast beautiful 19th-century architecture and parks. They combine access to outstanding natural environments with an enthusiastic and engaged local population. The challenge is to stop thinking about them in terms of decline and rather as live-and-work destinations of the 21st century.

Heather Brown receives funding from the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration for the North West Coast (NIHR200182). Heather has also previously received funding from UKRI and NIHR.

Amelia Simpson is seconded to Blackpool Council. She receives funding from NIHR Health Determinants Research Collaboration.

Reuben Larbi is seconded to Blackpool Council. He receives funding from NIHR Health Determinants Research Collaboration (HDRC).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.