The first thing visitors to Tupac Shakur: Wake Me When I’m Free will see is a towering 12ft bust of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti, the words “2 DIE 4” etched beneath her. Fans of Shakur will recognise this as a larger-than-life reproduction of one of the rapper’s chest tattoos, a tribute to his mother Afeni Shakur, who he referred to as a “Black queen”. On his 1993 track “Something 2 Die 4”, Shakur recalled the words of guidance she once offered him: “You know what my momma used to tell me / If ya can’t find something to live for / then you best find something to die for.”

It’s an apt introduction to the immersive new exhibition in downtown Los Angeles, which has been curated and assembled by Shakur’s estate, because as well as bringing together a remarkable collection of artefacts from the rapper’s short but explosive musical career, the exhibit also serves as a powerful reminder of the formative influence his mother’s experiences in the Black Panther Party had on his life and work. The 20,000sqft exhibition opened last Friday and is set to remain in Los Angeles for a limited time (tickets are currently on sale through to 1 May) with as-yet-unspecified plans for the show to eventually tour North America and cities around the world. Twenty-six years after Shakur was murdered in Las Vegas, the thought-provoking exhibition avoids gimmickry – there’s no sign of the Tupac hologram that appeared at Coachella in 2012, for example – in favour of foregrounding the rapper’s activism and politically conscious art.

To that end, the exhibition begins with a short film installation featuring graphic images of slavery, lynchings and police brutality, which puts Shakur’s life into historical context. It is narrated by a recording of Shakur explaining why he was unconcerned if critics found the truths revealed in his music uncomfortable: “What about when I felt uncomfortable for 400 years?” That leads into a room dedicated to Afeni Shakur and her activism with the Black Panthers, centred on her 1969 arrest as one of the Panther 21, a group who were accused of planning attacks on New York police stations. At the centre of the room is a totemic sculpture of a Black fist raised in strength and defiance. It is titled “Hang In There”, and at its base sits a pile of 350 black handcuffs, one for every year of the jail sentence with which the 21 Black Panthers were threatened (they were all acquitted by a jury in 1971).

Another member of the Panther 21 was Jamal Joseph, Tupac’s godfather, who serves as a special advisor to the exhibition. He also donated some of his own treasured possessions, including a book of haikus that an 11-year-old Shakur wrote for Joseph and sent to him while he was incarcerated in 1982. In a statement about the exhibition, Joseph explained why Afeni Shakur’s legacy is so intertwined with her son’s music. “Afeni was the baddest Black Woman to walk the planet,” said Joseph. “She raised awareness and shifted the atmosphere wherever she went. Tupac’s brilliance shined brighter than the sun… Afeni and Pac challenged, reimagined, and transformed history.”

The section dealing with Shakur’s time growing up in Harlem, the Bronx and White Plains is brought to life with a series of oversized sculptures, including his beloved tricycle and the football helmet he’d wear as he rode it, zooming around the house pretending to be an astronaut or whatever else his imagination might dream up that day. These innocent images of childhood contrast with the realities of growing up under police surveillance. Another oversized sculpture, this time of a huge jar of peanut butter, illustrates the times that Shakur helped family members cover doorknobs and handles with peanut butter to stop the FBI dusting them for prints, a moment he immortalised on the track “As The World Turns”: “Poppa runnin’ from the Feds / Puttin’ peanut butter on the walls to hide his prints / Me on my own, not yet grown but only man of the home.”

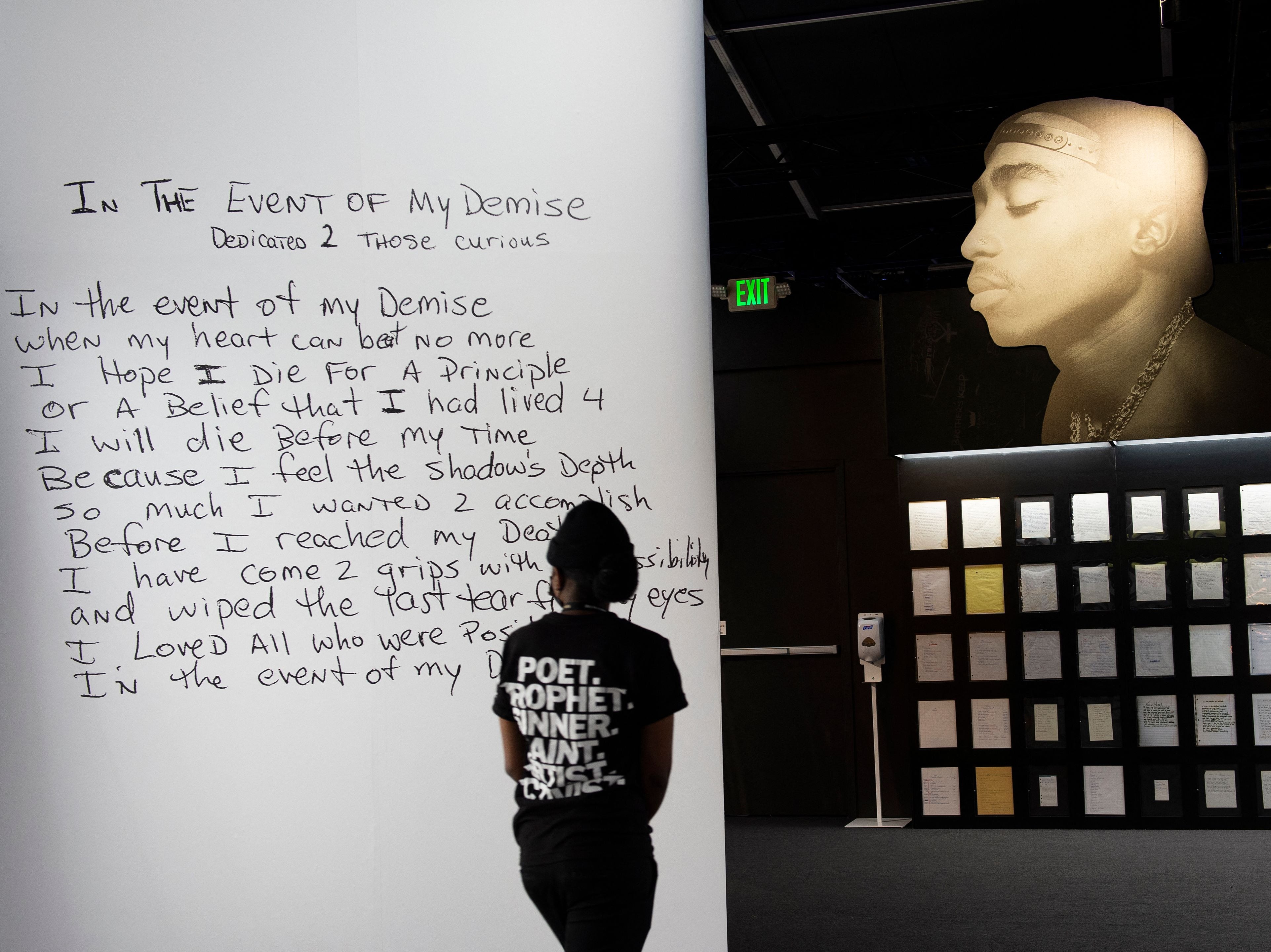

From the time he was a child, Shakur wrote constantly, filling countless notebooks. The most remarkable room in the exhibition, and the one in which Shakur’s fans will want to linger the longest, is filled with hundreds of pages drawn from these books. Whole walls are covered with Shakur’s handwritten lyrics, poetry, screenplays and business ideas. It’s astounding to watch Shakur’s ideas take root and blossom across these pages, and to notice the images he returns to again and again. There are handwritten notes from an autobiography that he began writing as a teenager in 1989, titled The Rose That Grew From Concrete, as well as notes from his mother, which offer insight into their relationship. One chiding message from Afeni reads simply: “Tupac / Please find meaning in the greatness of cleaning and responsibility etc. This room is a pig sty. I will not accept it. - A.”

After Shakur moved to California in 1988 he quickly started to bring the ideas he’d sketched out in those notebooks to life. The exhibition collects handwritten notes from his 1991 debut record 2Pacalypse Now with mementos such as call sheets and pay stubs from Juice, his first major acting role, which was released the following year. Even as Shakur struck out on his own, his mother’s influence was never far away. In a section of the exhibit designed to look like a prison cell, footage of Shakur being interviewed in prison in 1995 plays on one wall as he describes how his relationship with his mother evolved. “My moms is my homie,” says Shakur. “We went through a lot of stages. First, we was mother and son… then it was like drill sergeant and cadet. Then it was like dictator – little country. After I moved out and I was on my own, I came back and it was like some prodigal son type of thing, where now she respects me as a man and I respect her as a mother for all the sacrifices she made.”

When he was released from prison in 1995, Shakur wasted no time getting back to work. In the next room, we step inside a recreation of Can-Am Studios, where Shakur went to record his fourth album All Eyez On Me. Above the mixing desk we see footage of Shakur recording at breakneck pace. Next comes a space dedicated to his various music videos, including a treatment for 1996’s “To Live & Die in LA” sketched out in Shakur’s by-now familiar handwriting.

Towards the end of the exhibition, there’s a collection of outfits Shakur wore during the last 11 months of his life, including the Versace suit he wore to the 1996 Grammys and the leather vest he’s wearing on the cover of All Eyez On Me. Along with these familiar tokens of celebrity, we’re also granted some insight into his California home. We see a statue of a female African warrior, which once stood guard outside his front door, and a suggestion of domesticity in Shakur’s ornate wooden Scrabble board.

The exhibition ends, inevitably, abruptly. While you walk down the final corridor, decorated with falling rose petals, it’s hard not to imagine what Shakur might have achieved with more than 25 years on this planet, and startling to remember how much he did. The last thing visitors see before they leave is another larger-than-life sculpture, this time of a single red rose erupting up through a tower of concrete. It is accompanied by Shakur’s words, elucidating the image that as a teenager he planned to name his autobiography. “We wouldn’t ask why a rose that grew from the concrete has damaged petals,” says Shakur. “We would all celebrate its tenacity, we would all love its will to reach the sun. Well, we are the roses, this is the concrete and these are my damaged petals. Don’t ask me why. Thank God, and ask me how.”

Tupac Shakur: Wake Me When I’m Free is open now at Canvas @ LA Live. For tickets and more information, visit: wakemewhenimfree.com