An effort to memorialize the Illinois Black Panther Party has exposed a divide over how to preserve its legacy — and who should tell its story.

At the heart of the conflict is an effort to add the history of the Illinois chapter of the party to the National Register of Historic Places. The listing would note several locations crucial to the group’s history, including many in the Chicago area.

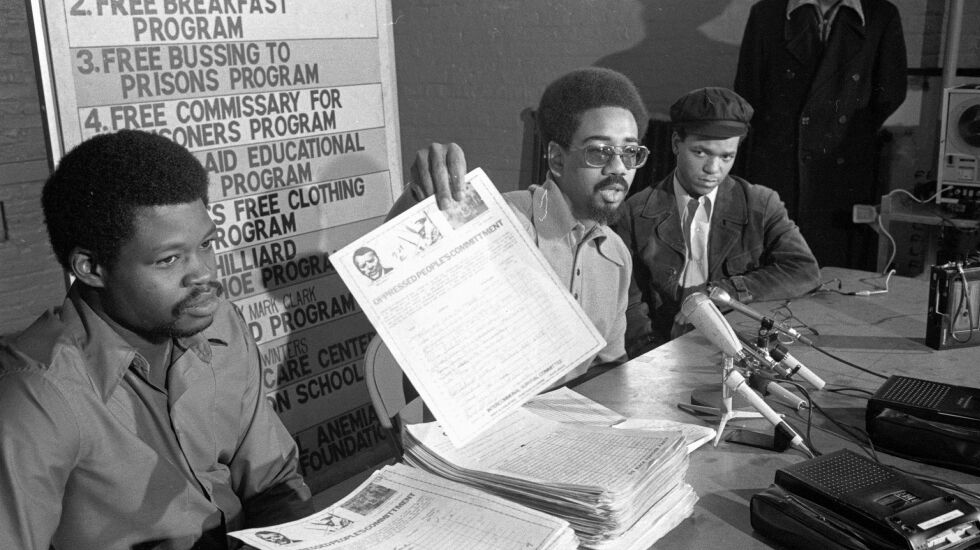

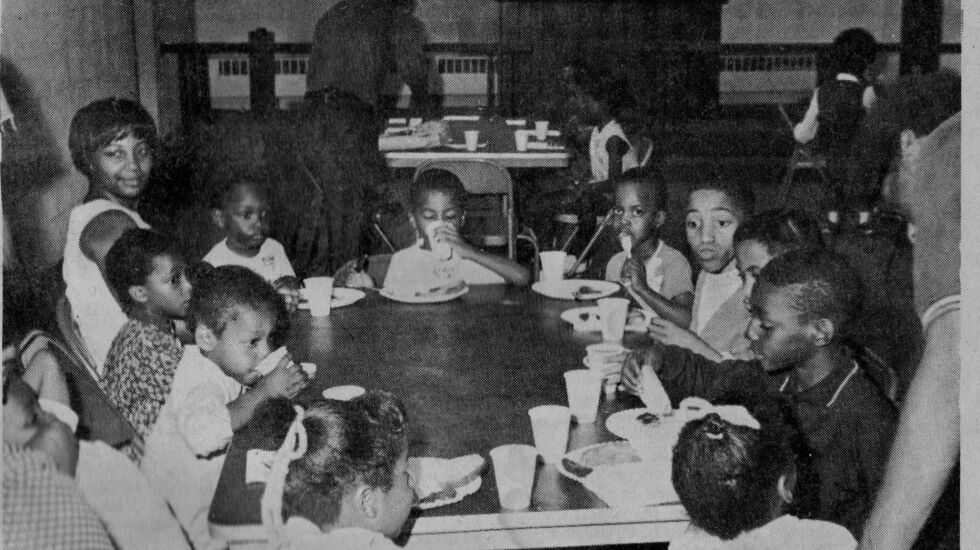

The Black Panther Party, founded in the 1960s, grew out of the Black Power movement and provided services such as free breakfast and free health care around the country. The FBI, however, considered it a violent, gang-like organization and launched a counterintelligence program against it.

Supporters say adding the history to the National Register would highlight the group’s importance. Opponents argue it would perpetuate a slanted portrayal of the group.

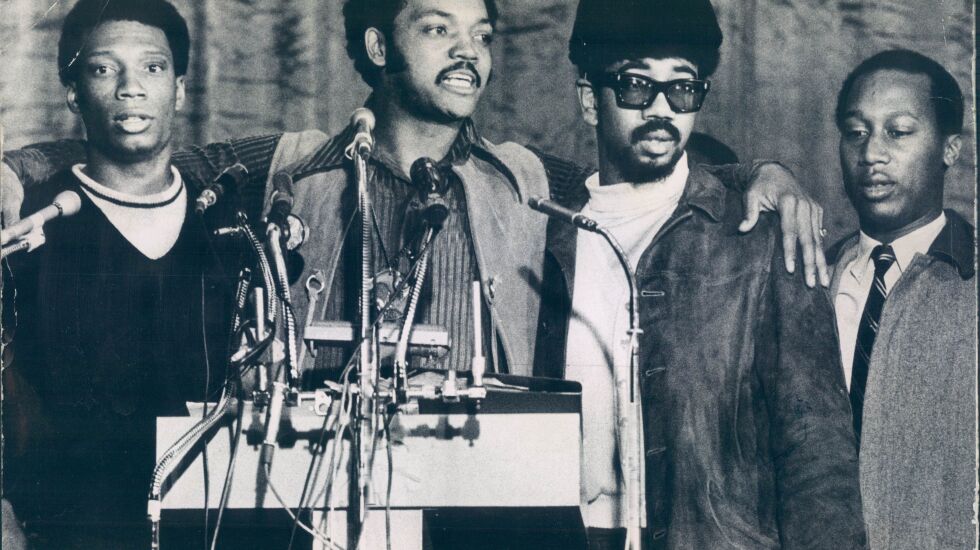

“Our purpose is to make the Illinois chapter an official part of the state’s history,” said Leila Wills, who spearheaded the project and collected letters of support from more than 20 former Black Panthers, including party co-founder Bobby Rush, who later served in the U.S. House of Representatives, representing a Chicago-area district for three decades.

Not among the supporters, however, is Fred Hampton Jr., chairman of the Black Panther Party Cubs. Hampton Jr. is the son of former Black Panther leader Fred Hampton Sr., who was assassinated during a 1969 raid led by Chicago police and orchestrated by FBI counterintelligence efforts.

Hampton Jr. led a coalition opposed to the National Register recognition, saying misinformation spread by the FBI has damaged the party’s legacy. This project would further that harm, he said, because its leaders lack respect for the Black Panthers’ history.

“This is not their story to tell,” he said. “We come from a community that prefers a demolished truth, as opposed to a structured lie.”

A state advisory council voted unanimously late last month to approve the nomination effort, after a Chicago commission chose in early October not to comment on the project due to the concerns raised by Hampton Jr. and his supporters.

The National Park Service, which makes the final call on accepting or rejecting the nomination, received the proposal Nov. 8 and has until Dec. 26 to respond, according to James Gabbert, a historian for the National Register.

The National Register proposal, in the works for three years, includes a report on the history of the Black Panther Party and a survey of eligible properties supporters believe could be considered for the register if the owners express interest.

While this kind of listing does not directly add any sites to the National Register, it “serves as a basis for evaluating the National Register eligibility of related properties,” according to the guidance for submitting a listing. National Register listings are evaluated for their association with historically significant events or people, or their architectural importance. Proposals are first considered by the state before being sent for final approval from the Park Service.

Some sites listed in the survey:

• The Church of the Epiphany, also known as the People’s Church, now the Epiphany Center for the Arts, where the party operated its Free Breakfast for Children program, held rallies and hosted Hampton Sr.’s last meeting. While already on the register for other reasons, the church, 201 S. Ashland Ave., also would be included under this new listing.

• Truevine Missionary Baptist Church, then St. Bartholomew Church, where the group also operated its Free Breakfast for Children program.

• First Baptist Church of Melrose Park, where Hampton Sr.’s funeral was held.

Some locations, including the former chapter headquarters and the site of a free health clinic, already have been demolished.

To compile the research for the proposal, Wills interviewed more than 30 former members.

“It is important to include the historical significance of the ongoing struggle of the Black Panther Party throughout the United States as a voice for parity and justice. The struggle of Black People to overcome racism is a reality that must be told, addressed and ended before we can move forward as a nation,” former member Wanda Ross wrote in her letter of support.

Wills’ parents were both party members, volunteering in the breakfast program and other efforts. She said talking with her parents about these places, especially those that no longer exist, motivated her to work on this issue.

Adding a site to the National Register is primarily a state-level process but requires approval from the National Park Service. Local governments with historic preservation programs, such as Chicago, can provide a comment but are not required to.

A National Register listing doesn’t prevent demolition or restrict what owners can otherwise do with a property. But it does protect a site from negative impacts from state and federal projects, said Andrew Heckencamp, the National Register coordinator for the Illinois State Historic Preservation Office. Once a state nominates a site, he said, it would be “extremely rare” not to make the list.

Still, Wills said, documenting the Black Panther history to these sites is important to create resources to help educators and researchers.

Wills will begin the second phase of her project to document and preserve the Panthers’ history, placing markers at the former sites of some important structures, to preserve that history “for when none of us are here anymore.”

Wills said Hampton Jr. and his mother never responded to numerous requests to discuss the project or offer feedback. In 2019, they worked together on landmarking Hampton Sr.’s childhood home in west suburban Maywood. That status, approved by the village in April 2022, prevents demolition. The building is now a museum dedicated to Hampton Sr. Working on that project and researching the chapter inspired Wills to work on the National Register project.

“Everything I’m doing now, I did for the Hampton House,” she said. “That’s when I first, myself, really researched the work of the chapter, meaning by location. I didn’t know that their work was so extensive through the state of Illinois.”

Wills said Hampton Jr. cites “nothing but trigger words, emotional appeals and innuendo” for why he opposes what she’s doing.

Hampton Jr. said, “The prime players who have been pushing for this acknowledgment of the historical sites of the Black Panther Party have, ironically, expressed a disdain, a hatred for the Black Panther Party.”

He added he has “no doubt” giving these sites historic recognition would further spread misinformation, and the party is still working to undo the harms it already has suffered through “nefarious intent and naiveté.”

But Wills said her research has been driven by firsthand accounts from former members themselves, who have also read and reviewed every section of the proposal, rather than relying solely on media. She is continuing to make updates based on their edits and requires multiple members to corroborate facts.

“There’s so many intricacies with the context and the smear campaign that the party has been under for the last 50 years. It is true that the FBI planted material in the press for years, decades, so all of those are land mines that you have to avoid,” Wills said.

Founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, the party was a reaction to widespread poverty, police violence and lack of economic and educational opportunities Black people in America faced.

The group spread across the U.S., demanding self-determination for the Black community, decent housing, education on Black history and an end to police brutality. It organized armed self-defense groups to combat police violence and also formed “survival programs” targeting food access, health care and other necessities.

During the Panthers’ active years, the FBI used counterintelligence tactics so extreme that years later, the agency apologized for “wrongful uses of power.”

Wills said she wants people to know how significant the Panthers’ impact was.

“The breakfast program was not just confronting hunger, it was also a medical issue, because the children were not healthy,” she said. It “showed the commitment that the party had to the people and to the poor.”

Documents in the FBI’s files show it considered the Panthers an extremist organization that advocated the use of violence to overthrow the U.S. government. Countering that FBI portrayal is what motivates Hampton Jr. now.

“The history of the Black Panther Party, it still remains under attack,” Hampton Jr. said.

But supporters of Wills’ project said they, too, want to correct a false version of the Panthers’ history.

Ward Miller, executive director of Preservation Chicago, said the project provides an opportunity “to acknowledge the great accomplishments of the Black Panther Party.”

Miller previously worked on the designation of the Church of the Epiphany. Amending that site’s listing to include the church’s history with the Black Panther Party was something they “couldn’t talk about” during the preliminary report for the site, he said.

“I think it’s wonderful now that we’re in an age and a place where we can talk about all of these histories and share them,” Miller said.

For both Wills and Hampton Jr., the Black Panthers’ commitment to the community is what stands out.

“The Black Panther Party, contrary to so many incorrect narratives,” Hampton Jr. said, “was birthed out of love, out of love for the people.”

Sites included in proposed National Register listing