A new children’s book, Black and Bold Queens: Women in Ghana’s History explores the lives of 16 notable female pioneers and leaders in the West African country, with a strong focus on the independence period of the 1950s and 1960s. It was written by Dr Nikitta Dede Adjirakor, a writer and academic researcher in east and west African literature and popular culture. We asked her about this trailblazing project.

What made you decide to write the book?

In 2020, during the first months of the COVID pandemic, I kept thinking about the stories we document and whose history is compiled and kept. In Ghana, this is overwhelmingly male.

This led to my attempt to make a list of the women I know in Ghana’s history off the top of my head. It was extremely difficult. It took days to compile without resorting to Google or any books. I realised we needed a reference book, especially for children who needed to know this history. And it needed to be accessible, interesting and fun.

How did you choose which women to include?

I wanted to make sure I had a variety of women to accurately represent Ghana’s geography as well as different occupations and educational levels. Some of the women in the book are educated and others not. Their careers are vastly different – pilots, doctors, queens, market women, photographers. Some were deeply engaged in politics, others weren’t. All the women, except the famous warrior queen Nana Yaa Asantewaa (1830 – 1921), were active in the independence period of the 1950s and afterwards. I wanted to focus on how women shaped the country’s legacy in different ways.

Read more: Children's book revolution: how East African women took on colonialism after independence

The biggest challenge was finding accurate sources for the stories of the women and this also shaped who was chosen. It took about two years of research. A lot of available internet sources provided inaccurate dates or biographies. The academic sources were behind paywalls. As an academic, I was able to access some of them, but it reinforced my belief that we need a book that’s easily accessible and available – and accurate.

Can you tell us about three of the women?

The Krobo Queens are queen mothers from the Krobo ethnic group. In the 2000s, AIDS was killing many and education was lacking on the disease. Seeing the devastating impact of the disease on their people, the Krobo Queens banded together, sought accurate information from medical personnel and organised awareness programmes in their communities to help prevent and manage it.

I love this story because it’s a collective effort to create change within an entire ethnic group. It’s also a story of resilience among women – these queen mothers often fostered children orphaned by the disease. The change they effected was truly generational.

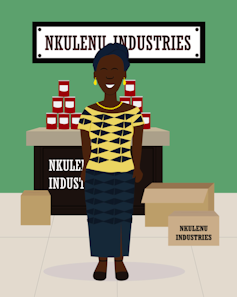

Esther Afua Ocloo (1919 – 2002) understood the importance of economic freedom and started her own business early in life, making and selling marmalade. Her story teaches us to understand the concepts of economics, money and power. In particular, the relationship between money and power.

She was concerned with how women living in poor conditions could have access to loans and other financial incentives.

She created resources to advocate for policy change and directly help women across the world, co-founding the organisation Women’s World Banking.

Her company, Nkulenu Industries, is still a leading producer of processed traditional Ghanaian foods.

The story of Felicia Abban (1935 –) is important in a country where, for years, creative careers like photography were not considered valuable.

She learned from her father at a young age, becoming an apprentice in his photography studio at 14, before opening her own. She was one of the first professional photographers in Ghana.

Her photos remain a powerful look into the past, showing the clothing and styles of women in the early independence period.

What was behind the illustrations?

My wonderful illustrator Denyse Gawu-Mensah and I wanted to create illustrations that were representative of the women and captured details of their lives. We wanted them to be vivid and colourful.

For women whose stories span multiple careers and interests, the illustrations also display their multitudes. For instance, Theodosia Okoh (1922 – 2015) designed Ghana’s flag and influenced the design of many African flags due to the pan-Africanist independence movement. She was also interested in the hockey movement in Ghana. Her illustration captures all of these things.

Adinkra symbols incorporated in the overall design of the book are Akan symbols that express specific concepts and messages. Other Ghanaian ethnic groups also have similar symbols.

They’re usually visual representations of proverbs, sayings and concepts with historical and philosophical meaning. They’re often incorporated into woven clothing, pottery and furniture.

Together with the designer for the book Mike Anim, we wanted to use them to symbolise the legacies of the women within Ghana.

For instance, Nana Yaa Asantewaa, who led the Ashanti army to war against the British, is represented with the adinkra symbol akofena, which means “sword of war” and symbolises courage and valour.

Why do these women’s stories matter?

They matter because they provide a rounder representation of life. Many of these women only exist as footnotes in the stories of men. They haven’t been adequately documented and discussed. This means that young people grow up without an accurate representation of Ghana’s development.

Read more: Imbokodo is a long overdue series of children's books on South African women

I hope to use the book to encourage young people to document the stories of women around them, to see that all stories matter and that these stories provide the foundation on which the next generations learn, develop and adapt to challenges.

Nikitta Dede Adjirakor does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.