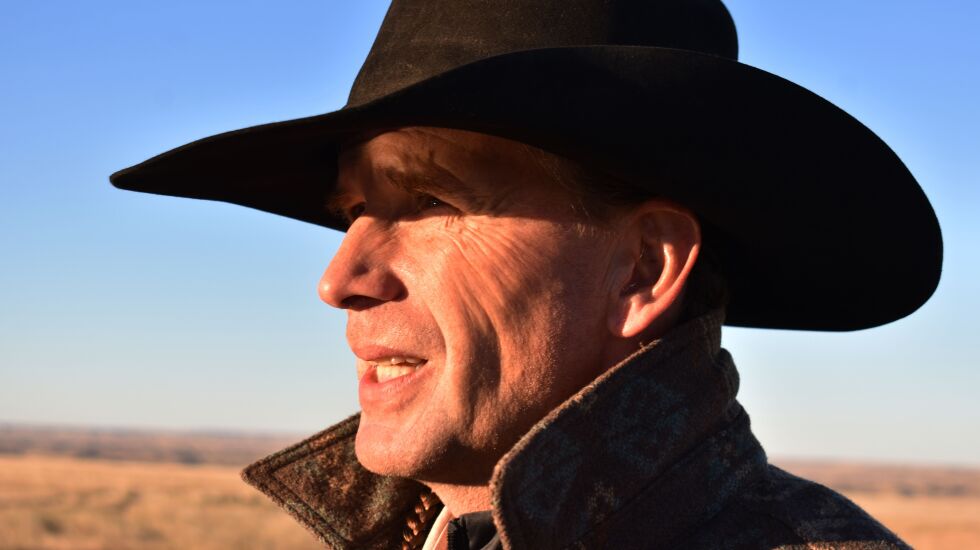

BULL HOLLOW, Okla. — Ryan Mackey quietly sang a sacred Cherokee verse as he pulled a handful of tobacco out of a zip-close bag.

Reaching over a barbed wire fence, he scattered the leaves onto a pasture where a growing herd of bison — popularly known as American buffalo — were grazing in northeastern Oklahoma.

The offering represented a reverent act of thanksgiving, according to Mackey, 45, and a desire to forge a divine connection with the animals, his ancestors and their faith.

“When tobacco is used in the right way, it’s almost like a contract is made between you and the spirit — the spirit of our Creator, the spirit of these bison,” Mackey said. “Everything, they say, has a spiritual aspect. Just like this wind, we can feel it in our hands, but we can’t see it.”

Decades after the last bison vanished from their tribal lands, the Cherokee Nation is part of a nationwide resurgence of Indigenous people seeking to reconnect with the shaggy-haired animals that occupy a crucial place in centuries-old tradition and belief.

Since 1992 the federally chartered InterTribal Buffalo Council has helped relocate surplus bison from locations such as Badlands National Park in South Dakota, Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming and Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona to 82 member tribes in 20 states.

“Collectively those tribes manage over 20,000 buffalo on tribal lands,” said Troy Heinert, a Rosebud Sioux Tribe member and executive director of the InterTribal Buffalo Council, based in Rapid City, South Dakota. “Our goal and mission is to restore buffalo back to Indian country for that cultural and spiritual connection that Indigenous people have with the buffalo.”

Centuries ago, an estimated 30 million to 60 million bison roamed the vast Great Plains of North America, from Canada to Texas. By 1900, European settlers had driven the species nearly to extinction, hunting them en masse for their prized skins, often leaving the carcasses to rot on the prairie.

“It’s important to recognize the history that Native people had with buffalo and how buffalo were nearly decimated,” said Heinert, who is a South Dakota state senator. “Now, with the resurgence of the buffalo, often led by Native nations, we’re seeing that spiritual and cultural awakening as well that comes with it.”

Historically, Indigenous people hunted and used every part of the bison: for food, clothing, shelter, tools and ceremonial purposes. They did not regard the bison as a mere commodity but as beings closely linked to people.

“Many tribes viewed them as a relative,” Heinert said. “You’ll find that in the ceremonies and language and songs.”

Rosalyn LaPier, an Indigenous writer and scholar who grew up on the Blackfeet Nation’s reservation in Montana, said there are different mythological origin stories for bison.

“Depending on what Indigenous group you’re talking to, the bison originated in the supernatural realm and ended up on Earth for humans to use,” said LaPier, an environmental historian and ethnobotanist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “And there’s usually some sort of story of how humans were taught to hunt bison and kill bison and harvest them.”

In Oklahoma, the Cherokee Nation, one of the largest Native American tribes, with 437,000 registered members, had a few bison on its land in the 1970s. But they disappeared.

It wasn’t until 40 years later that the tribe’s contemporary herd was begun, when a large cattle trailer — driven by Heinert — arrived in 2014 with 38 bison from Badlands National Park.

Since then, births and more bison transplants have boosted the population to about 215. The herd roams a 500-acre pasture in Bull Hollow, an unincorporated area of Delaware County about 70 miles northeast of Tulsa, near the small town of Kenwood.

For now, the Cherokee aren’t harvesting the animals, focusing on building the herd. But bison, a lean protein, could serve in the future as a food source for Cherokee schools and nutrition centers, said Bryan Warner, the tribe’s deputy principal chief.

Originally from the southeastern United States, the Cherokee were forced to relocate to present-day Oklahoma in 1838 after gold was discovered in their ancestral lands. The 1,000-mile removal, known as the Trail of Tears, claimed nearly 4,000 lives through sickness and harsh travel conditions.

While bison are more associated with Great Plains tribes than those with roots on the East Coast, the newly arrived Cherokee had connections with a slightly smaller subspecies, according to Mackey.

“We don’t speak the same language as the bison,” Mackey said. “But, when you sit with them and spend time with them, relationships can be built on … other means than just language alone: sharing experiences, sharing that same space and just having a feeling of respect.”