A 113-year-old West Loop building that once housed a dance club that became the birthplace of house music will become a Chicago landmark, thanks to designation poised for final City Council approval on Wednesday.

Chairing his first Zoning Committee meeting, Ald. Carlos Ramirez-Rosa (35th) proudly pushed through a designation for the building at 206 S. Jefferson St. — a building with great personal meaning to him and his colleagues in Chicago’s LGBTQ+ community.

The three-level nightclub known as “The Warehouse” started as a membership-only venue popular with gay Black men. But it fast became what Preservation Chicago has called a “dance floor of freedom” for a more diverse crowd, a racial rainbow of music lovers who found a “sense of community” in the sound and scene.

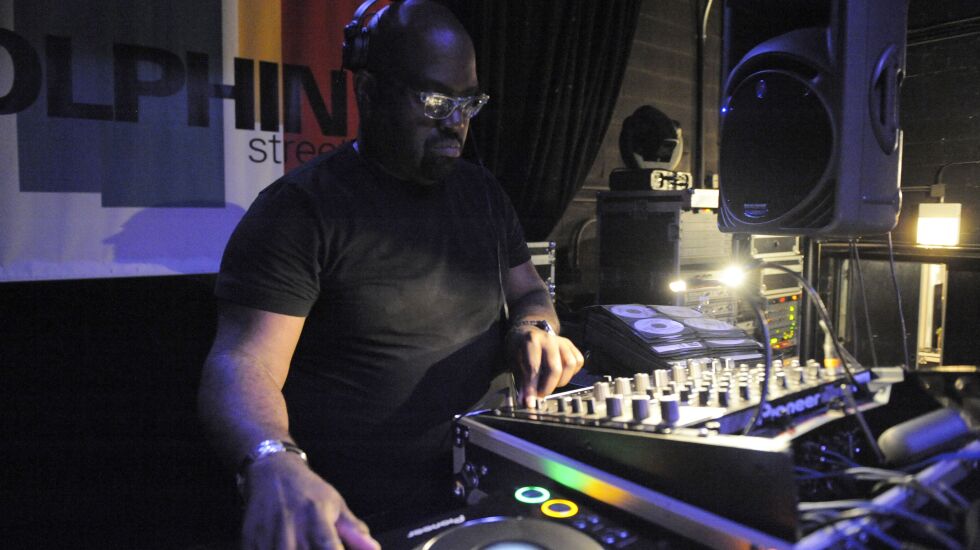

From 1977 through the mid-’80s, the resident DJ at the Warehouse was Frankie Knuckles, a record producer and remix artist hailed as the “Godfather of House Music.”

House music was described Tuesday as a genre characterized by a “driving beat, a mode of lyrics and lush orchestration.” Knuckles made it happen by “combining different genres of music, including disco, R&B and Gospel.”

“As a proud gay man and as a Chicagoan, house music is very near and dear to my heart. House music is one of the many gifts that Chicago has given to the world,” Ramirez-Rosa told his colleagues.

“It was born at the Warehouse with DJ’s like Frankie Knuckles. Openly gay men, lesbian women, queer people, trans people who were expressing resilience in the face of hostility and hate. Who refused to be put down and who chose instead to celebrate love and life.”

Ald. Bill Conway (34th), whose ward includes the new landmark, called it a “momentous day” in Chicago history.

He noted 14,000 people had signed the landmark petition circulated by Preservation Chicago. And Conway thanked Ramirez-Rosa for “pushing this as a direct introduction so we could get it done for Pride Month.”

Ald. Walter Burnett (27th), the City Council dean who will turn 60 on Aug. 16, said he was among those who partied hearty at the Warehouse.

“It wasn’t just LGBTQ people going there. It was everybody. We all partied there. It was a place where everyone felt safe. It was a place where everyone felt that they weren’t discriminated against,” Burnett said.

“Being a young man from Cabrini-Green, hanging out with guys who worked in corporate America and women who worked in corporate America and just partying and having a good time. It just was a great place. It made everyone feel good. And those parties lasted for a long time.”

Burnett, calling Knuckles a “good friend,” said he was proud to have been on hand when the stretch of Jefferson Street by the Warehouse was designated Honorary Frankie Knuckles Way in 2005.

“We loved that guy. He was just a genuine, charitable good person here in the city of Chicago. … He’s loved all over the world. You go all over the world, you hear Frankie Knuckles’ music being played in every country,” Burnett said.

The Warehouse building was used for manufacturing until 1975. That’s when it was purchased by New York native Robert Williams, who arrived in Chicago at a time when the city’s nightlife scene “paled in comparison” to the Big Apple.

“The Warehouse was Williams’ attempt at offering Chicago’s clubgoers something different,” Preservation Chicago wrote in its report recommending landmark status.

After installing a “world-class sound system,” Williams needed a DJ who “understood its potential.”

Enter Francis Nicholls Jr., also known as Frankie Knuckles, who was lured away from Manhattan’s Continental Baths nightclub.

With Knuckles at the turntables, “Word began to spread that the Warehouse was the only place in Chicago to hear a new type of music, one that forged a harmony between soul, R&B, disco, electronic, and gospel,” the report states.

During the nightclub’s early days as a “members-only gay club frequented mostly by Black men,” disco music was ”wildly popular ... especially in the gay and Black communities,” the report states.

“Growing resentment against both groups in the 1970s manifested in a public disdain towards disco music” culminating in Disco Demolition night at Comiskey Park spearheaded by Chicago DJ Steve Dahl, Preservation Chicago wrote.

“As the Warehouse’s popularity grew, the club’s membership eventually moved away from a largely gay and Black clientele and came to include Chicagoans of all backgrounds.”