When we think of the most far-out musicians in the universe, primarily we think of guitarists and keyboardists, of sound-controllers so attuned to their vast collections of instruments and gadgets they assume the mantle of masters of musical time and space and all satellite regions of aural heaven between.

What we tend not to think of are drummers. Oh, we acknowledge the privileged place Bill Bruford holds in the Yes story. We certainly aren’t going to argue with Carl Palmer over who put the P into you know who. And of course we preferred the days when Phil Collins sat at the back of Genesis.

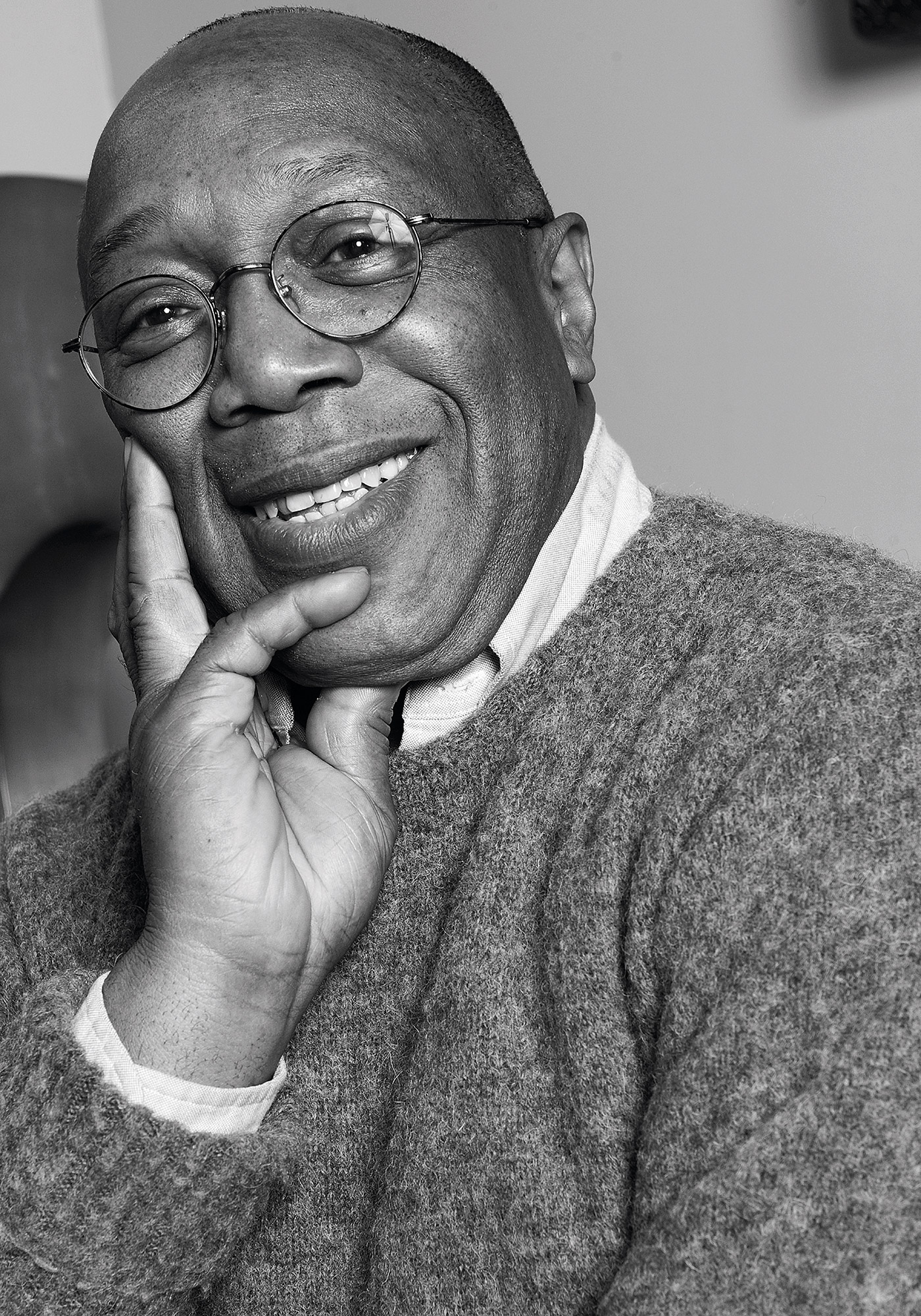

But none of them could be acclaimed for composing some of the most sonically challenging, emotionally charged and mentally stimulating music ever committed to memory. Unlike the man sitting opposite me this bright cold London morning: none other than Billy Cobham.

He will be 68 this year [this article originally appeared in Prog Magazine in 2012], yet the handshake he offers is as warm and bone-crushing as one would expect from the man who helped usher in a whole new genre of music through the sheer force of his percussion talents. Billy Cobham is to the drums what Jimi Hendrix was to the guitar. Not just one of its greatest exponents, but someone who rewrote the entire rulebook. Billy didn’t play drums with his teeth, or set them on fire with lighter fuel. He did something more amazing. He pushed musical boundaries until he turned what was basically a rhythm backbone into a veritable lead instrument. One with a voice, a texture and tone that could whisper to you one moment about strange new worlds waiting just out of the corner of your eye, then lift you with one hand and hurl you directly onto the surface of them.

Not that he’s willing to acknowledge any of this. According to Billy, “I just went where the work was.”

Yeah, but what work. His first two solo albums, 1973’s Spectrum and 1974’s Crosswinds were so game-changing suddenly every self-respecting drummer in the world wanted to do the same, to front their own freewheeling rock-jazz-progressive outfit. But by then Billy had already moved on. Indeed, the past 30 years have seen him collaborating with fellow jazz-rock colossi George Duke and Stanley Clarke, plus some of the biggest names in rock, including Peter Gabriel, Jack Bruce, Bob Weir, Carlos Santana and Carly Simon.

He shrugs: “For me, I can play alone and feel comfortable expressing myself. But then I want to go and do something with someone else. For me it’s about making music, it’s not about making sport. It’s not about getting it. It’s about letting it.”

Cobham was born in Panama but brought up in New York, where he graduated in 1962 from the High School Of Music And Art. His big break came in 1970 when Miles Davis hired him to play on sessions for the double album Bitches Brew, now regarded as a classic, the template from which all jazz rock fusion would derive.

“I walk in and on my right, why it’s Chick [Corea]. And there’s Larry Young on organ, and Keith [Jarrett], plus Joe Zawinul... er, I guess that takes care of the keyboards. Then you look up and there’s Bennie Maupin [bass clarinet], Dave Holland on bass, Harvey Brooks on electric bass...”

Aside from occasional chords and perhaps a hint of melody, it was up to the musicians to make it up as they went along. On the title track you can actually hear Davis whispering instructions when to solo and when to “keep it tight.” Bitches Brew was also the first modern album to use the studio itself as an instrument, utilising dozens of different edits and sound effects, including tape loops, delays, reverb and echo effects; experiments that echoed the new thinking then taking place in progressive rock.

“Miles was like a painter,” recalls Billy. “He would be playing something then turn around and point to somebody and they would play. It was all about knowing when to go and when not to go. It was all about art, feeling, thought...”

White middle class jazz critics didn’t get Bitches Brew. But rock audiences freaked out on it, giving Miles his first gold album.

“From that point forward it just started to progress,” says Cobham. “It was breaking the shackles and testing the waters of rock and jazz at the same time. And it caused a big problem for the intelligentsia. They couldn’t make the rules and theories and everybody would just go along. It didn’t work like that anymore.”

Another prominent member of Davis’ ‘electric’ band at this time was a young guitarist from Doncaster, Yorkshire, named John McLaughlin, whose astonishingly original guitar experimentations had been the defining factor in both alienating Davis’ older jazz audience and enrapturing his newer, rock-buying audience. Cobham and McLaughlin played a major role on Miles Davis’ next album A Tribute To Jack Johnson recorded in 1970, but issued in February 1971.

When McLaughlin invited Cobham to jam at New York rehearsal studio Baggy’s, it led to the formation of one of the most innovative rock bands in early 1970. “The time I’d been there before, Hendrix was there. Then on the ground floor Fleetwood Mac moved in for six months.”

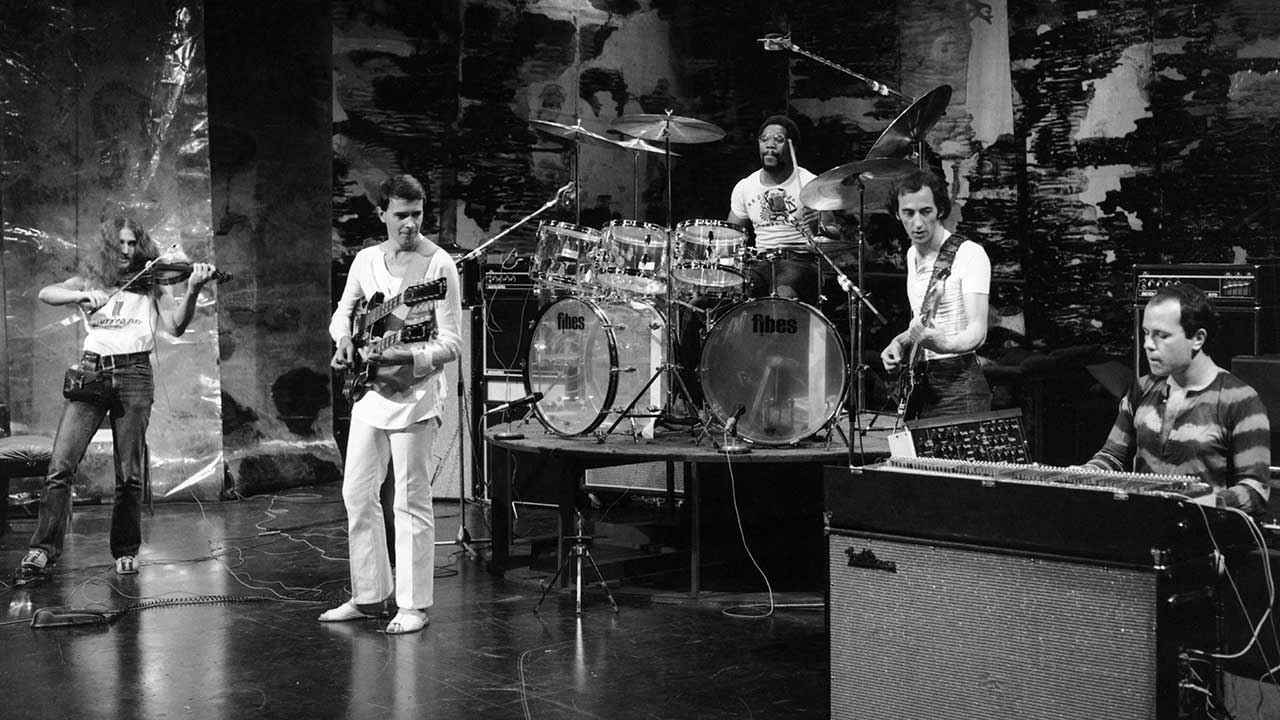

Drummer and guitarist spent the next three weeks there rehearsing alone. “Eight hours a day. It began as just playing anything, then things started to develop.” Soon they were joined by a multinational group of talents including the Irish-born Rick Laird on bass, Czech keyboardist and synth player Jan Hammer and US violinist Jerry Goodman. Taking their name from one given to McLaughlin by his Indian guru, Sri Chinmoy, they became known collectively as The Mahavishnu Orchestra and in 1971 released one of the most singularly mind-blowing rock albums ever made: The Inner Mounting Flame.

Led by McLaughlin’s trademark electric double-necked guitar – six-string and 12-string – ramped up by previously unheard new textures in Laird’s crazy electric violin and Hammer’s unrestrained Moog, the original incarnation of the Orchestra managed just two studio albums before imploding, but both remain cornerstone recordings in the ever consciousness-expanding story of progressive rock music in its earliest, most uninhibited configuration.

Melody Maker called it, “music of the gods”. But it was the word ‘fusion’ that was most used to describe The Mahavishnu Orchestra: instrumental music that didn’t need lyrics or singers to speak to your soul. So you got spitting fire on tracks like Vital Transformation, while others such as A Lotus On Irish Streams are as serene as the surface of the moon. And then there were opulent tracks like Open Country Joy that began deep under the surface before exploding into sonic stars that lit up the indoor sky.

Live though was where the flame turned into a furnace. “We never played like the record,” Cobham recalls. “Live we went some place else.” A track like the breezy Hope, barely two minutes long on 1973 album Birds Of Fire, would be transformed into a lengthy series of leaping improvisations led by Cobham’s famous lightning fast press rolls. Or as Billy explained at the time: “We start to play, and we lose contact with time.”

They would record the shows, “but only for us. Not great sound quality, just little cassettes. Sometimes you wouldn’t hear it. But years later I’d go, ‘Wow! That was burning!’”

Suddenly The Mahavishnu Orchestra had become the band other bands looked up to. “Oh, they were amazing,” Chris Squire, bassist in Yes said, “not just technically, but in every way. They were very pure.”

Not so “pure” that their egos didn’t clash. The track The Noonward Race – a cosmic duel between drums and guitar – only became that way after a punch-up between Laird and Goodman knocked over Hammer’s keyboards. Drummer and guitarist kept playing throughout, though, and the result became the finished recording.

By 1973, though, the flame had all but flickered out and sessions for a third album at London’s Trident Studios were abandoned midway through. Pressed now, almost 40 years later, on why the most innovative band of the early 70s didn’t stay together longer, Cobham shrugs. There were “major social problems”. Something a late 1973 tour with Carlos Santana only aggravated further.

McLaughlin had become friends with Santana after introducing him to Sri Chinmoy, the guru giving Carlos his own ‘divine name’ of Div Pak. Keeping only Billy from the Orchestra, McLaughlin and Santana recorded Love Devotion Surrender, and launched an American tour that placed the two guitarists firmly in the spotlight – and Cobham more in the shadows.

McLaughlin claimed he simply wanted to “explore into deeper fields of consciousness”. But according to Cobham, “it’s not easy working with people who aren’t interested in your opinion anymore.”

Cobham instead recorded his first solo album Spectrum. Featuring 22-year-old future Deep Purple guitarist Tommy Bolin, Spectrum signalled mainstream recognition for both Cobham and fusion music, and set every other drummer in rock talking in awed tones. Said Bolin, “That’s how Ritchie [Blackmore] first heard about me. Spectrum to me was a kind of new music that could have had a wide appeal.”

When the follow-up, Crosswinds, took Cobham’s new sound to even more people, he seemed set for a career playing to arenas full of long-haired jazz and prog fans. Instead, he abandoned that direction and began collaborating again with blue-chip jazz stars like George Duke and Stanley Clarke. With the former he claimed to experience “astral projection” while playing, while the latter was “the closest I got” to hard rock, albeit done to its own innovative style.

Between then and now there have been nearly 40 more solo albums and even more collaborative projects, live albums and soundtracks. The day we meet he is about to begin a three-night run at Ronnie Scott’s in London with his current band, which he says “reflects my whole life”.

He’s also working on the third part of “a series of music for my parents who passed away about five years ago” – part of his Palindrome triptych of releases. As he says, “This is living, breathing music happening right now.”

Nevertheless, one couldn’t help but be intrigued by his unannounced one-off reunion with McLaughlin, which took place at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 2010. The first time they had played together since their acrimonious split, he smiles as he recalls the occasion.

“We walk onstage and we don’t know what we’re gonna play. I said to him, ‘Do you know any of the old tunes?’ He says to me, ‘Yeah, I know ’em’. I said, ‘Okay, what do you wanna play?’ He says, ‘I didn’t say I knew ’em all.’ I said, ‘What do you know?’ He says, ‘I know the beginnings. I don’t know the ends...’ But that’s kind of how it always was with us.”

With that he lets out a long, loud, last laugh...

This article originally appeared in issue 25 of Prog Magazine.