It might be hard to imagine the words "Big Prawn" and "Australian heritage" in the same sentence, but the peculiarly Aussie phenomenon of plonking oversized, kitschy attractions on the side of the highway is, these days, about as vintage as a rotary phone.

The sceptics call them an eyesore; a great lump of fibreglass or cement from a decade when, if my dad's haircut was anything to go by, aesthetic sensibilities were not a huge priority for us as a nation.

Now, more than 20 years on from when many of these attractions were built, it would seem that the Big Things' sole purpose is to gradually fall into disrepair, at once coming to pieces while also - in their utter refusal to actually die - making a pretty compelling argument that just about everything that came from the '80s had a half-life to rival some power plants.

Biodegradable? These things most certainly are not.

In the other camp, though, are those of us who not only think our big things are pretty neat, but see them as just as formative to many of our childhoods as the Play School windows. Tourist traps or not, if you were lucky enough to be one of the generation of kids who grew up on family road-trip holidays, big things have an undeniably special place in your heart, good taste be damned.

I have vivid memories of my sister and I, bundled into the back seat of the Commodore on the way to the beach for school holidays, driving mum and dad to distraction asking how far we were from the Big Banana roughly every 15 mins after we left the home town limits.

There was something exciting about finding a new one unexpectedly on the road and making a fuss until dad begrudgingly agreed to stop at the servo with the big potato on it (or maybe it was meant to be a mango with some sun damage? Who knows).

The point was, it was something novel and strange and a little bit quirky to break up the monotony of the road. They were one of the first things to teach us as youngsters that, sometimes, the journey really is as good as the destination.

News this week that the big prawn at Crangan Bay had, through suspected foul play, lost its head has brought up some strong feelings in both camps for our national collection of big stuff. But, vandalism aside, the act also raises some questions about what we're meant to do with these things as their age starts showing.

It's hard not to draw parallels between our own "big" prawn at Crangan Bay with the other (bigger) prawn at Ballina in the Northern Rivers, which in 2010, looked like it was bound for the scrapheap before Bunnings purchased the site of the former servo where it was installed and saved the 35-tonne monument.

It cost about $500,000 to build in 1989, when Hungarian brothers Attila and Louis Mokany, who owned a chain of NSW petrol stations, added the prawn (and incidentally, the big ram at Goulburn and the oyster at Taree) on top of their businesses. It cost Bunnings another $400,000 to save it around 2013 when it was moved and a tail was added as part of the trade giant's philanthropic adoption. And in April this year it was under scaffolding again as Sydney twin-sister painting duo Rebecca and Rachel Neill were called in to revive the local icon after floods devastated the area a year earlier.

Rebecca Neill, who has worked in theatre and set painting for more than 20 years, and now runs her specialist paint finishing business Set For Art, whose latest projects included working on the Stan series 10 Pound Poms and Class of '07, stopped short of giving an exact dollar figure on the seven-day restoration project but given the monument's history, it's not beyond the pale to think of it the prawn worth a million dollars (or near enough to).

"There are always tight budgets when you're doing heritage restoration on any level," Mr Neill said. "I think that is where is seems like some philanthropic businesses take them on; there has to be a bit of philanthropy. Funding is kind of low in heritage restoration, but I think the big things need to stay - they're part of our contemporary history for sure. They're like museum pieces now; they need to be looked after.

"There were some politics in Ballina over who was paying for (the restoration) because the community had already been through so much," Ms Neill admitted, "But after it was done, I think it lifted everybody's spirits.

"It attracts tourists and business ... and considering that a lot of highways bypass these places now, it's an excuse to take a detour."

Bunnings' adoption of Ballina's prawn may be the exemplar for how to save a big, unwieldy, public attraction in an age when words like "big and unwieldy" struggle to get purchase, but Ms Neill said despite how we might feel about our big things they are essentially public art and they need the love and care that public art demands if they are to stand the test of time.

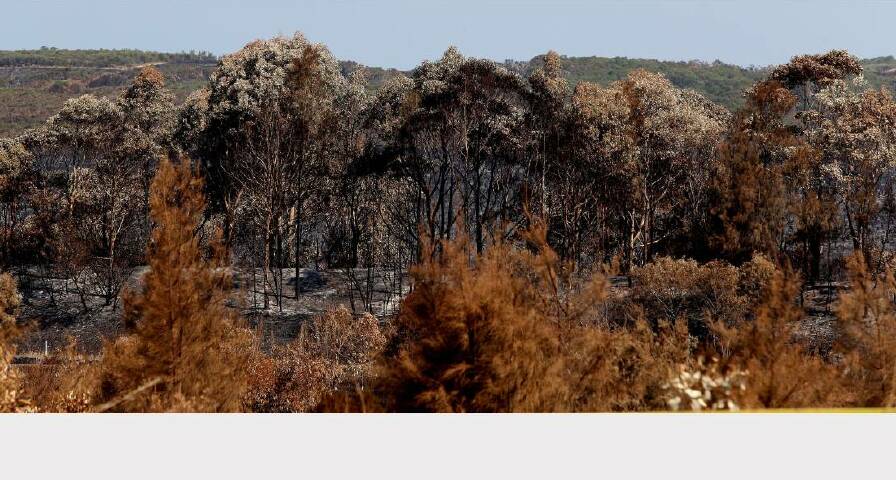

When a bushfire tore through the former service station on the Pacific Highway at Crangan Bay in 2013, the big prawn was only thing to survive the blaze and has since stood alone on an empty lot.

The giant fibreglass installation sits adjacent to the ruined site where the servo once stood and, since roughly Friday, has been left headless.

Police officers attached to Lake Macquarie Police District and Tuggerah Lakes Police District told the Newcastle Herald nothing had been officially reported on the incident yet.

"I can't believe someone would go to the effort of getting a grinder, and no-one noticed," Ms Neill said, of the act of vandalism that claimed the prawn's head, "It's pretty violent.

"It's sad that someone has defaced it like that. Someone went to a lot of effort to make it at some stage. I think it's part of our history in some way."