A rainy September morning, an eclectic group of nature experts and amateurs is gathered about a bush in Sipna jungle near Panshet, around 25 kilometres away from the city of Pune.

”This is a great find!” Rajat Joshi, the Pune district coordinator for Big Butterfly Month announces. We all peer obligingly. It is a pupa of a butterfly belonging to the Pansy family; perhaps the Lemon Pansy we saw fluttering around a while ago.

For this group, that is indeed a good find. In September, butterfly and moth (together the order Lepidoptera) enthusiasts have an even more crystalised reason to pursue their passion for their pet creatures— it is Big Butterfly Month across India. It’s a citizen science, conservation and outreach effort centred on butterflies and to some extent their less popular cousins, the moths.

What is Big Butterfly Month about?

Shantanu Dey, founder-convenor of Big Butterfly Month and avid butterfly expert based in Mumbai, says the main purpose of this month is to bring awareness to the broader challenges in conservation.

”There are two parts to it,” he says. The first part is the science— the attempt to increase citizen counts of butterflies— lots of data handling, data collecting, and recording of species.

Citizens are encouraged to maintain regular timed counts in a set area, making detailed notes and repeating the exercise on a fortnightly basis. Some of this data will find its way online through citizen observation portals like iNaturalist, Indian Biodiversity Portal and Butterflies of India. During Big Butterfly Month, there is an observable uptick in such logs.

The second aspect of Big Butterfly Month is outreach activities, aimed at increasing general awareness of the winged critters— perhaps being able to identify a few species and how not to harm them. The idea, according to Mr. Dey, is that people “get interested in butterflies in general and in the ecosystem in its totality.”

This year, 22 States are involved in Big Butterfly Month; an attempt has been made to cover all districts in the nation, including far-flung areas like Ladakh and the Andamans. The event has also crept over the border into Pakistan— Pakistan Butterfly Society held an inaugural Butterfly Walk of Pakistan at Maple School and College in Saidu Shareef, Swat, as part of a regional initiative titled the Big Butterfly Month- Indian Subcontinent 2023.

As Mr. Dey says, “for experts there are other avenues; for everyone else, there is Big Butterfly Month.”

Also read: First-ever butterfly survey in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve records 175 species

A Pune outing

During the Sipna walk, there is already deep enthusiasm to locate species, extending from creatures that look like bright splotches of colour to those that seek to escape attention by mimicking dead leaves. At one point, the group is divided between seeing a hyperactive Skipper fluttering through snakeweed plants or a Common Evening Brown, a crumpled leaf lookalike that likes the ground beneath the shade. Both are brown, and both are beautiful to this group.

The group is also enthused alike by caterpillars munching away at leaves- a Plain Tiger caterpillar on a garden lantana plant, a Red Pierrot caterpillar inside a Rui (Calotropis gigantea) leaf, and a Tailed Jay caterpillar barely distinguishable from his green leafy background.

Moth caterpillars too are spotted, and noted; a particularly intense level of enthusiasm is bestowed to female butterflies hovering around plants searching for a place to lay eggs— some of them tiny white dots that would otherwise escape scrutiny.

The Sipna jungle is a unique place, a manmade forest with a mix of exotic and native plants. Started by Pramod Nargolkar in 1989, it is now run by his wife Nayana Nargolkar. The forest was soon a large 22-acre venture, named Sipna for a river in Melghat Tiger Reserve— a favorite of its founder. In 2004, following the devastating Indian Ocean tsunami, Mr. Nargholkar, then visiting the Andamans, was reported missing, along with several others from Pune. But from 2005, the project soldiered on, under the careful tending of Mrs. Nargolkar, and 10 to 12 acres now remain.

A butterfly garden is a recent addition to the mix, created last year to provide a different attraction for students and children. Mrs. Nargolkar and Mr. Joshi came in contact a few months ago, and around 30 to 40 plants were added to the garden. These include butterfly host plants like milkweed, snakeweed, periwinkle, garden lantana and Bryophyllum plants.

This marks the first time a Big Butterfly Month event is taking place here.

Chasing butterflies in Mumbai

If Sipna marks a private endeavour to conserve plants and encourage biodiversity, the Maharashtra Nature Park (MNP) represents a government initiative in the same vein— in a different city. A park created by plantation on what was originally a dumping ground/landfill, MNP borders the Dharavi area in Mumbai— known more in popular culture for less-than-genteel dwellings than for natural beauty.

It was here that, on September 10, another BBM event was held by a local NGO called Naturalist— albeit of a slightly different shade. This one was about creating butterfly gardens, with details about host plants for larvae and nectaring plants for adult butterflies —and how to potentially build one in your own home. The NGO, in collaboration with the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA), held a lecture followed by a trail to identify both butterflies and the plants that beguile them.

Sachin Rane, Naturalist co-founder and leader of the day’s event, says the park is Asia’s first project of this nature—37 acres of manmade forest on an erstwhile dumping ground.

The future sustainability of landfill -turned- ecozone MNP is something experts will perhaps deliberate over with mixed opinions. But the place sees a score of butterflies — ranging from ubiquitous grass yellows to common leopards, Danaid eggflys, white orange tips, and red Pierrots. More than 85 butterfly species can be found in this park, according to Mr. Rane. The greater Mumbai region, he says, hosts 165 species, if you include Panvel and Navi Mumbai.

During the event, Mr. Rane notes the most important requirements for a butterfly garden— sunlight for several hours a day, plants which are hosts for specific butterfly species (for example, the tamarind is a host plant for the Black Rajah and Bryophyllum plants is a host for red Pierrot caterpillars). These host plants should also be within a 50 metre-radius from a flowering plant.

There is a hands-on activity as well— everyone gets to plant a tree in MNP; each tree is the host plant for a particular butterfly species. And at the end of the event, each participant receives Jamaican Blue Spike plants (also called blue snakeweed or vervain) — a species mentioned by Indian Biodiversity Portal as attracting butterflies to its flowers and being a host plant for Death’s Head Hawkmoth caterpillars.

The NGO has more events in the works— it plans to host a butterfly trail at the Conservation Education Center on September 23, while a Butterfly Race is being planned for September 24, where participants will be tasked with photographing as many species as possible from the morning till sunset, in locations across Mumbai and its suburbs, including Navi Mumbai and Panvel.

Documenting the known and finding the unknown

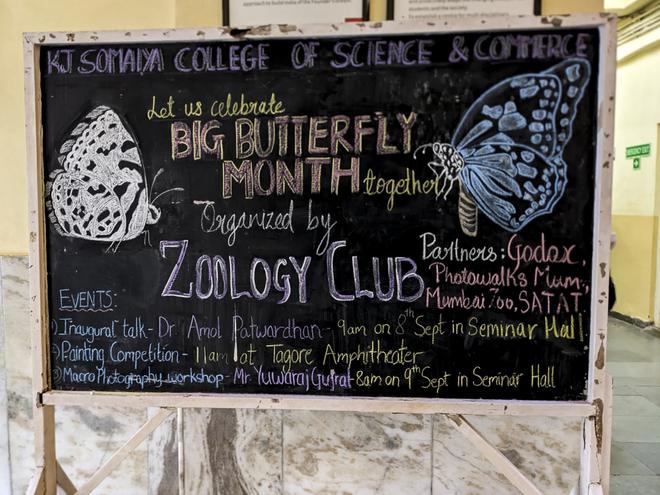

This month has seen variety in programming— if there are introductory sessions for amateurs and data collection walks for the slightly more knowledgeable, there are fun activities for students and children—like a butterfly painting competition on the K.J Somaiya campus in Mumbai’s Vidyavihar area.

On September 9, under the aegis of Big Butterfly month, Club Zoology of the Zoology department of K.J. Somaiya College of Science and Commerce also organised a macro photography workshop, in collaboration with Photowalks Mumbai and photo equipment company Godox. Even at 8 in the morning, the hall is filled with bright faces. The subject— macro photography — is of keen interest to anyone trying to document creatures that range from the length of a fingernail to as big as a man’s face.

The speaker is noted wildlife photographer Yuvraj Gurjar, who has held exhibitions and won international awards for his work centred around many species— spiders, orchids, mushrooms, beetles, and of course, butterflies. Back in their day, when they were “wandering in forests in the 80s, a camera was like a Cinderella,” Mr Gurjar said, highlighting further that even regular cameras may not suffice for the purpose. As he says, a birding lens cannot shoot butterflies, which can range from the large Atlas moth, measuring 10-12 inches, to the tiny Grass Jewel, a mere 14 millimetres.

Also read: Spot a Blue Pansy butterfly on a periwinkle flower

As he talks the crowd through how to select a background to make the subject pop, and how to light up a subject, Mr. Gurjar scrolls through his own work, not just of butterflies — of a scorpion with its babies on its back, snake cannibalism and a mosquito oozing a drop of extra blood, which won a national award.

One thing he makes clear— as nature lovers, wildlife photographers are not to cause harm to the subject. “Leave it as it is,” he says. When asked about whether flashes may harm butterflies, Mr. Gurjar is less severe. Insects have compound eyes, he points out; they are startled but not harmed by photography.

The crowd tests its newly acquired knowledge in the field. The college has a biodiversity garden, created in 2019 under the guidance of the iNaturewatch founder Dr V. Shubhalaxmi, funded by the US Consulate under a mentorship programme for youth leaders in environment conservation. Now, the little patch hosts many butterfly species— tailed jays, blue tigers, glassy blues, common Mormons, and crimson roses.

At every event, participants milled around capturing shots of little creatures. If generating interest was the aim of Big Butterfly Month, it was clear that it had been piqued, in three groups of around 20 people, at various locations across Maharashtra.

Sparking a citizen science movement

But I wondered about the other aspect— conservation. Were we, as amateur enthusiasts, adding to our environment or taking away, I wondered morosely, as I saw the leaves flattened by our footsteps in Sipna. “There is a lot of regrowth here,” Mr. Joshi reassures me — if I come back a month later, all of this will be renewed.

And citizen scientists are hard at work, holding timed counts on butterfly walks— in Bangalore, Mysore, Dehradun, Pune, Jammu & Kashmir. The Indian Butterfly Monitoring Scheme (IBMS) was launched in 2021, after a few local monitoring efforts proved fruitful, chiefly in Bengaluru. Earlier this month, IBMS was also launched in Mysore, by Dr. Krushnamegh Kunte, Associate Professor at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bengaluru.

Citizen counts online rise during this September. Mr. Joshi told local media that last year, nearly 1,336 observations were registered by 55 enthusiasts in Pune during the month of September— with around 130 butterfly species documented. This is an uptick from 2019— when Big Butterfly Month was first launched at a national scale— with around 200 observations.

According to data from the Big Butterfly Month website, this year’s tally stands at 10,894 observations from 608 users, from 205 districts. Last year saw 14, 497 from 867 users. Maharashtra leads the table in number of observations and users— like last year.

That there is enthusiastic participation from this region is no surprise. After all, a local Big Butterfly Month was launched in Mumbai 7 years ago— by Sohail Madan and Shantanu Dey with the aid of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS). It then went national in 2019. Pune Butterfly Club was in fact launched due to Big Butterfly Month, says Mr. Dey. Further, the Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot, have a sizeable number of species— a report cites 337 species sighted in the area.

They are of course no match for the Northeastern region, which hosts an astounding number of lepidopteran species— one paper places it at a mind-boggling 3600. But the prevalent ethnic strife in Manipur and its fallout across the region have tamped down outreach efforts in the region— although Mr. Dey informs me that counts are still going on.

The eventual aim is to harness civilian interest to track populations of butterflies nationwide, a data-gathering exercise that will bear fruit not in days and months, but years. Keeping track of butterfly populations in various parts of the country is expected to shed light on the health of local ecosystems; butterflies are regarded as a keystone species and are crucial pollinators for several flowering plants.

After a morning of rain, a consistent sun only emerges as our walk through Sipna winds down. We have spotted 27 species— a good find for a rainy day.

As we all leave the forest, the little path is filled with light, and more butterflies, now undisturbed by human presence, slowly emerge. As the grass yellows flutter around calmly, in leisurely fashion, I find myself hoping that Big Butterfly Month succeeds in its mission.

On September 23 and 24, Naturalist Foundation will hold a trail and a Butterfly Race in Mumbai. Learn more here. Find other Big Butterfly Month events near you here and here.