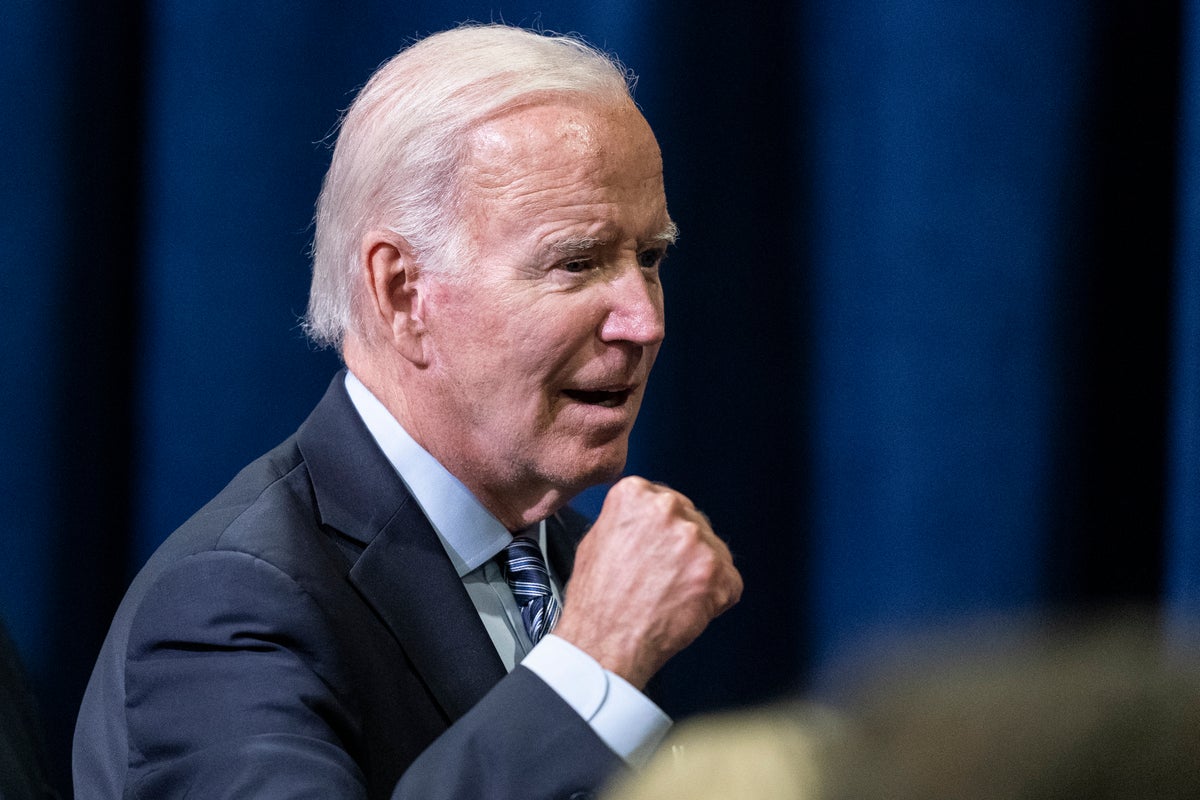

President Joe Biden wants to put the spotlight on a rare bipartisan down payment on U.S. manufacturing when he visits Ohio on Friday for the groundbreaking of a new Intel computer chip facility.

Biden heads to suburban Columbus to take a victory lap just as voters in the state are starting to tune in to a closely contested Senate race between Democratic Rep. Tim Ryan and Republican author and venture capital executive JD Vance. They're competing in a former swing state that has trended Republican over the last decade.

Intel had delayed groundbreaking on the $20 billion plant until Congress passed the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act. Both Ryan and Ohio Republican Gov. Mike DeWine, who is facing Democrat Nan Whaley in his reelection bid, plan to be at Friday's groundbreaking.

In his State of the Union address last March, Biden envisioned the Intel plant as a model for a U.S. economy that revolves around technology, factories and the middle class. The plant speaks to how the president is trying to revive American manufacturing nationwide, including in states that are solidly Republican or political toss-ups.

Chipmaker Micron committed $15 billion for a factory in Idaho, Corning will build an optical fiber facility in Arizona and First Solar plans to construct its fourth solar panel plant in the Southeast, all announcements that stemmed from Biden administration initiatives.

Factory work is one of the few issues going into November's midterm elections that has crossover appeal at a time when issues such as abortion, inflation and the nature of democracy have dominated the contest to control Congress.

Ryan had largely been hesitant to share a stage with Biden, as appearing with the country's top Democrat could hurt his chances in a state that backed Republican Donald Trump by eight points in both 2016 and 2020.

Ryan skipped the president’s July 6 visit to Cleveland to plug his administration’s efforts to shore up troubled pension programs for blue-collar workers. Biden nonetheless referred to him as the “future Senator Tim Ryan” and thanked him for his “incredible work” on the legislation.

The Youngstown-area congressman committed to appearing with Biden this week because of the importance of the Intel facility in a state that has long defined itself through its factories, mills and working-class sensibilities.

“This is a huge opportunity,” Ryan told CNN on Sunday. “The CHIPS Act that we passed is all about reshoring high-end manufacturing jobs.”

Yet in a Thursday TV interview with Youngstown's WFMJ on the eve of Biden's visit, Ryan said he is “campaigning as an independent.” When asked if Biden should seek a second term, Ryan said, “My hunch is that we need new leadership across the board, Democrats, Republicans, I think it's time for like a generational move.”

The open Senate seat in Ohio, currently held by the retiring Republican Sen. Rob Portman, is one of several hotly contested races that could determine whether Democrats can hold their slim majority in the chamber for the second half of Biden's term.

Several Democrats in competitive races have at moments sought to maintain some distance from Biden, whose public approval ratings have ticked up in recent weeks but remain underwater.

A spokesman said DeWine also plans to attend the groundbreaking, making him among the few Republicans on the ballot this year who are willing to share a stage with the president. Biden has in recent weeks said that extremist Republican lawmakers who refuse to accept the results of the 2020 election are a threat to democracy, a charge that has only intensified partisan tensions with control of the House and the Senate on the line.

Vance, the Republican Senate candidate in Ohio, hailed the Intel plant in a statement at as “a great bipartisan victory” for the state. He specifically applauded the “hard work” of GOP lawmakers including DeWine and Portman, but Vance pointedly made no mention of Biden.

The shortage of semiconductors has plagued the U.S. and global economies. It cut into production of autos, household appliances and other goods in ways that fueled high inflation, while creating national security risks as the U.S. recognized its dependence on Asia for chip production.

The mix of high prices and long waits for basic goods has left many Americans feeling disgruntled about Biden's economic leadership, a political weakness that has lessened somewhat as gasoline prices have fallen and many voters have grown concerned about the loss of abortion protections after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

The new law would provide $28 billion in incentives for semiconductor production, $10 billion for new manufacturing of chips and $11 billion for research and development. The funding follows similar efforts by Europe and China to accelerate chip production, which political leaders see as essential for competing economically and militarily.

Biden has pitched the legislation as a “once-in-a-generation investment in America” that could reduce U.S. dependence on Taiwan and South Korea at a time when China is seeking to expand its presence across Asia and its shipping lanes.

Lawmakers crafted the semiconductor investments to favor areas outside the wealthier coastal cities where tech dominates. That means change will be coming to the Ohio city of New Albany, where the Intel plant is being constructed, as well as nearby Johnstown.

Don Harvey, a sporting goods store owner and longtime Johnstown resident, likes the idea of a company making things again in the United States, and also providing potentially high-paying jobs for his five grandchildren down the road. Intel has said pay will average $135,000 for its 3,000 Ohio workers.

“What an opportunity in my eyes for Ohio and the United States as a whole,” said the 63-year-old Harvey.

Elyse Priest lives in a subdivision just up the road from the plant, and received a firsthand taste of the construction recently as she watched a huge cloud of dust roll up from the 1,000-acre site currently being leveled. Priest, 38, also knows the road-widening and added traffic will affect her commute to downtown Columbus where she works as a legal assistant.

“I’m concerned about losing the small town feel I’ve always had and loved about Johnstown,” Priest said. “But I know it’s going to be a greater good for the whole state.”