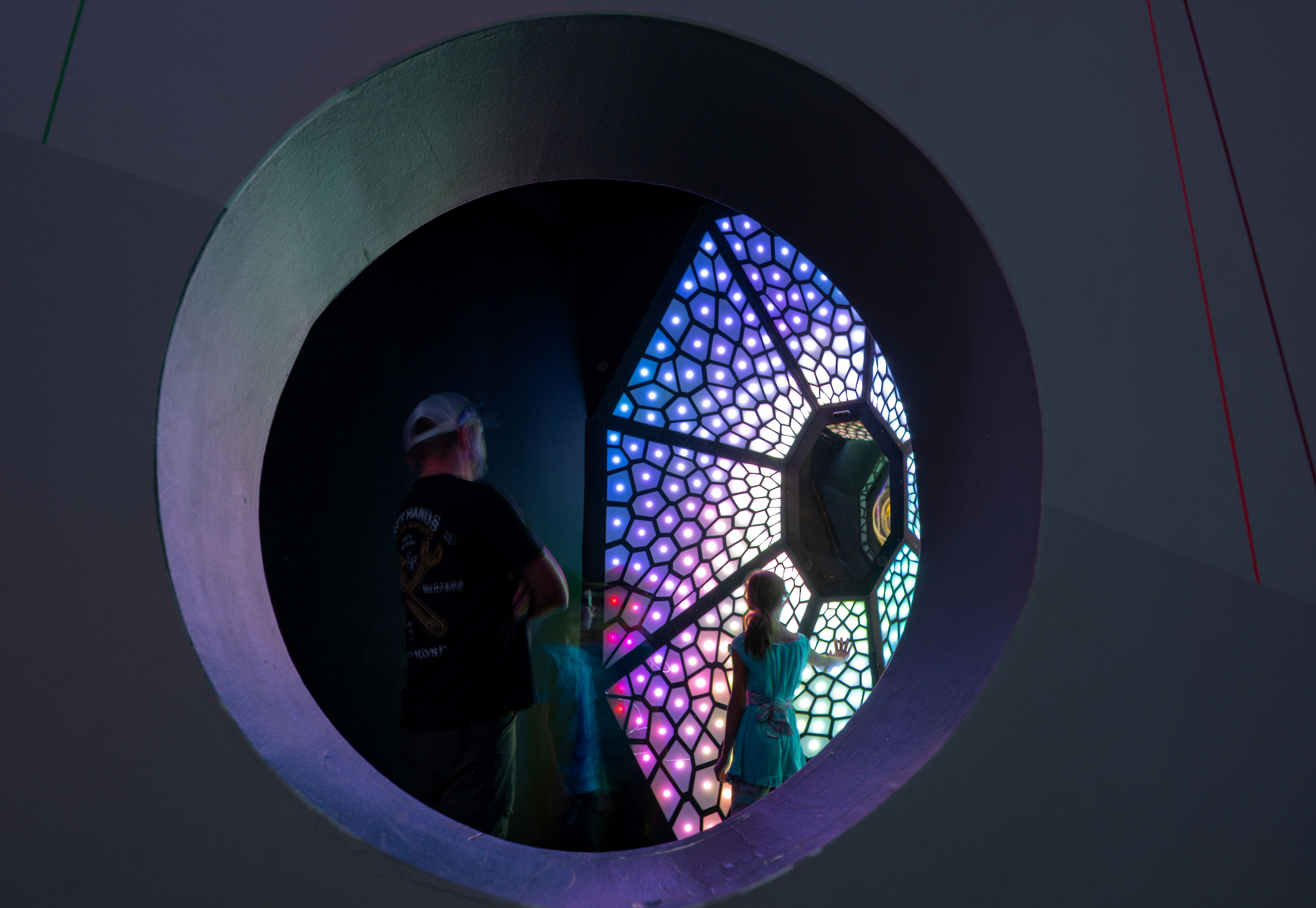

Above: The Neon Kingdom stage at Meow Wolf Grapevine, which the artist collective plans to use for community events and local musicians.

One moment, I’m standing in a drab hallway in the Grapevine Mills shopping mall, listening to the sound of blankness. When I enter “The Real Unreal”—the fourth permanent installation from artist collective Meow Wolf, and the first in Texas—I hear a gentle, whooshing static. It’s a palate cleanser, like a drink of water before tasting something new. Then, I step through a heavy office door into another world.

I’m in a lush suburban backyard in Bolingbrook, Illinois. Crickets chirp, mingling with the sound of traffic, far enough away that it adds to the sense of coziness and peace. The air even smells like earth and tomato plants from the vegetable garden, lit by gentle fairy lights.

Up ahead past the yard, purple light oozes from a two-story home’s circular dormer window. Below, the white streaks on the eggplants seem a little too drippy, the gourds a little too bulbous and tentacled. It only gets stranger when I step inside, where the walls bulge, the doors of the washer and dryer open into playground slides, and the fireplace and closet serve as portals to other dimensions—“Lightning Room,” a research base where scientists are trying to stop time, and a trippy neon forest replete with weird sculptures and fantastical creatures. The refrigerator door leads to “Brrrmuda,” a chilly hub where numerous pathways meet. Each of the hub spaces in the looping, maze-like exhibition leads to more rooms brimming with imaginative creations.

Opened in July in a former anchor store in this Texas-sized mall, the installation takes up over 24,000 square feet across two stories. “The Real Unreal” is the work of more than 150 artists—40 of them from Texas—that is both an avant-garde art gallery and an experiment in storytelling. When you attend a Meow Wolf exhibition, the goal is to make you feel like part of the art rather than a spectator. The result is a powerful experience that immerses visitors in uninhibited human creativity. Once you’re admitted, you can take as long as you want inside. Connor Gray, the PR manager, told me the average visit is about two hours, but some people stay all day.

This used to be a Bed, Bath, & Beyond. Now, we’re just beyond.

“This used to be a Bed, Bath, & Beyond,” Gray told me. “Now, we’re just beyond.”

According to Kaitlyn Armendáriz, the impact manager for Meow Wolf Grapevine and an adjunct art history professor at Collin College, the installation shatters the illusion that contemporary artwork is stuffy, dull, or exclusionary.

“The thing that excited me most [about Meow Wolf] was this idea of the breakdown between the viewer and the art,” Armendáriz said. “I really like that it’s truly art for everybody, and art for all.”

Meow Wolf rewards the curious mind with layer after layer to be peeled back. You can interact with almost everything—touch, read, and press. This is art you can hear and smell, too. The space is densely packed, with many rooms brimming with sculptures and crafted delights. In others, a single, massive artwork stands alone in its own gallery.

Because visiting Meow Wolf can be disorienting, the creators went to some length to make it as accessible as possible. Though you can crawl, slide, or take the stairs between levels, elevators are available. A kit with earplugs and other tools, to help autistic visitors and those who need a bit less sensory input, is available free from the gift shop.

While the attraction is child friendly, in September the team launched Adultiverse, special 21-and-up nights with bands playing in a colorful onsite event space with a bar. Although tickets for grownups start at $35—climbing to $50 on weekends and other peak days—organizers have given away more than 5,000 free tickets since they opened, many to students at schools the government deems to be the most impoverished. According to Armendáriz, they also offer significant discounts to all schools and community groups, even frequently to groups that aren’t formal nonprofit organizations.

“All of our sites donate tickets because cost and transportation, regardless of where you’re at, are the two biggest barriers to getting people into the arts,” she said, “so if we can eliminate the barrier of cost we’ll do that.”

Armendáriz told me that traditional museums have historically excluded marginalized groups, though she acknowledged many of them are working to become more diverse.

“It takes decades and decades to undo decades and decades of harm,” she said.

The power of Meow Wolf is that it started fresh, without all the baggage of traditional art galleries.

“Meow Wolf [came] in as this disruptor … because it was new and it was created by enthusiastic and idealistic individuals and was started with this mission to do good and to make art accessible,” Armendáriz added.

Meow Wolf began in Santa Fe in 2008, founded by a group of independent artists looking for unconventional ways to showcase their creations. Much like the Grapevine location, the Santa Fe installation is built around a suburban home that leads to galleries representing other worlds. From there, they took their installations to more cities, creating a unique theme for each. At each location, Denver (a planet where four alternate dimensions meet), Las Vegas (a superstore called Omegamart), and now Grapevine, core members of the Meow Wolf team recruited local artists and talent, from guides and gift shop employees to sound and lighting designers.

From the start, the artists’ unique and captivating vision attracted backers like the Game of Thrones author George R. R. Martin, who helped purchase their first location at a defunct bowling alley. Then, more than 800 people contributed to Meow Wolf’s Kickstarter campaign, which funded the alley’s conversion into an art space. Their popularity rapidly snowballed from there. For superfans of the Meow Wolf universe, “The Real Unreal” contains subtle references to previous installations, which encourages the community that’s grown around their art. Another location is slated to open next year in Houston.

“With Meow Wolf, it’s important that we take guests on that emotional journey,” Kelly Schwartz, the Grapevine general manager said.

If visitors aren’t immediately enraptured by the art, the mystery at the heart of “The Real Unreal” can hook them instead. Parts of the exhibition—like the home of the Delaneys and Fuquas—function both as installation art pieces and as a visual narrative told in letters, text messages, souvenirs, and scrapbooks.

In this home, a family of five has gathered to care for their ailing patriarch, the jazz musician Gordon Delaney. They include Gordon’s daughter Carmen, who just moved back in to help; Carmen’s childhood friend Laverne Fuqua; and Laverne’s two children, Jerrica and Jerid, who recently went missing.

A “missing” poster in the living room reads, “Jared, we are not mad. We just want you to come home.”

Other travelers crawl in and out of the warped fireplace with impossibly curving brick edges and stumble, dazed, out of the closet, a faraway look in their eyes. But I’m drawn to the color printout on the table. Have I seen this boy?

According to his sketchbook, one day Jared fell asleep in the weird closet under the stairs. When he woke up, the glass of water next to him contained a strange sea creature. It looks a bit like an axolotl, but is a unique species. It chirps and warbles, doesn’t seem to eat much food, and—strangest of all—only Jared seems to be able to see him. However, grandfather Gordon, who has gone blind, can hear it and likes the music it makes.

Jared’s clearly a sweet kid with a big heart and a special interest in sea creatures. Stickers, drawings, and pictures of aquatic life cover the wall and canopy over his bed. He’s nerdy (or fixated) enough that when he discovers the creature, he gives it a Latin name—Hapulusgarrulus Lapnoaquaflo, from the words meaning “soft” “talkative or chattering,” “tufted or crested,” “water,” and “flowering.” But for short, he calls it Happy Garry.

Gordon’s cough is getting worse, leading to a short-term hospitalization. When the family comes home, there’s no sign of Jared, who has followed his new pet Garry back into “The Real Unreal.” And no one has seen him since. Though the visitor never directly meets any of them, the story of Jared’s disappearance into other dimensions, written by Wisconsin science fiction author LaShawn Wanak, is laced throughout the museum.

“I like having those sorts of peaks and valleys in an experience, and having intentional design in that way so you might be in a room that’s super stimulating, but then you transition into a room where you can sit and reflect on that,” Schwartz said.

When I take a moment to rest on the comfy benches inside Baba Yaga’s hut, somewhere past “Brrrmuda,” I see Happy Garry staring back at me, floating in a jar with air holes punched in the lid, nestled among other sculpted oddities in a small glass cabinet. Baba Yaga’s hut, as is traditional in Russian mythology, stands on two giant chicken legs. Its feet cling to a massive tree in the psychedelic forest. Glowing mushrooms dot the tree trunk, pulsing and chiming as you touch them. A smiling guide in full drag makeup urged visitors to interact with the makeshift instrument or sent them off in search of a hidden, animated image of a hamster in a wheel. The guides help people into and—if necessary, when you get lost or overwhelmed—out of the attraction.

You can ask the guides for a “side quest” such as hunting “brain beans,” small doodles of plants hidden throughout the attraction. Each one contains a hashtag that you text to a phone number, also provided. In response, Dug, the head gardener sends a small cartoon image as a sort of trophy for finding the bean, with another optional activity: “To plant this bean, make a pair of binoculars w/ your hands and focus on 1 detail in the environment. Sow this image in your head garden.”

The exhibit is full of almost overstimulating highs, like the cracking electricity and flashing lights of the time scientists or the dance party you can start with a push of a button inside “Brrrmuda,” complete with a disco ball made from frozen food. One doorway in the fridge-dimension features cartoon paletas with wild faces made by local artist Carlos Donjuan. But there are also quieter moments that left me with a lingering, peaceful feeling.

One artwork that I returned to multiple times during my visit, was “Crystal Cloud Cave” by Lance McGoldrick. As quiet ambient music plays in a narrow room, one wall shows a constantly evolving, AI-generated sky, always unique, that slowly transitions from day to night, with sunsets and sunrises and, if you’re lucky, a glimpse of the aurora borealis. Along the opposite wall, reflective cubes, haphazardly stacked, mirror the skyscape—and the travelers passing through the corridor between—at unusual angles. I felt calm there in a way that’s hard to put into words. If there’d been a bed there, I’d have drifted off into inner space until closing time.

One of Dug’s clues sent me back to one of my favorite parts of the attraction, called “Lamp Shop Alley.” Like “Brrrmuda,” the Alley is one of the hub spaces that leads to other art. It looks like an alien marketplace full of strange offerings behind closed shop windows; glowing signs for other imaginary vendors written in unearthly languages cover the walls. There are toys too, like an ATM that challenges you to unlock its secret code. Through yet another doorway a deliciously seedy arcade full of custom cabinets that you can play. The whole vibe reminds me of all the “bizarre bazaars” found in fantasy and science fiction, strange shopping districts on faraway worlds. I imagine myself as a tourist stepping out of the “Hidden Capsule Motel” in search of breakfast on an early morning on some other planet. The air hums with the subtle sounds of a city waking up.

Scwartz said that the Alley is one of her favorite parts of “The Real Unreal.”

I love the level of detail, not only in the art that you see with your eyes, but in what you hear in the soundscape.

“I love the level of detail, not only in the art that you see with your eyes, but in what you hear in the soundscape,” she told me. “It’s just incredible … the way it echoes and bounces off the different walls, what the artists have been able to do.”

A talking vending machine in the arcade—next to a couch made out of what appears to be dirty laundry—offers pretend drinks like “Wake Up, Please!,” “Hydro Bang,” and “Code Cheddar: Cheese Drink.” A pixel face on the machine spouts sassy one-liners. As I watch, it comments on the short stature of a child who hits the lowest buttons. Of course, the vending machine itself opens up to another doorway.

“Hey, at least buy me dinner first,” the machine quips in its New York accent as someone steps through.

Not unlike the psychedelic experience that so much of Meow Wolf emulates, describing a visit to “The Real Unreal,” even with the help of photographs, is one of the more challenging assignments I’ve had as a reporter.

“[Meow Wolf] is a place that provides a sense of belonging, a place that allows everyone to be an artist, and to have a little bit of misfit alive in them,” said Kelly Schwartz, the general manager of “The Real Unreal.”

At the end of our interview, she told me, “We say ‘Once you go, then you’ll know’ because it’s really hard to explain. I want people to come curious, stay curious while they’re there, leave amazed, and tell all their friends.”

After three hours of exploring, I wasn’t ready to leave, but I did need a break. A small cafe and gift shop offers souvenirs and snacks, most of which are sourced from local vendors. I took a moment to think while sipping lemon and lavender fizzy water called “Gender Fluid,” the only genuine offering advertised by the vending machine inside the arcade. Its name is a pun on “genderfluid,” a form of nonbinary gender identity that’s neither male nor female but breaks the barriers in between. Soon, I was back inside searching for beans.

It’s so easy to get lost inside “The Real Unreal” that I was more glad for the legal requirement of exit signs than I’ve been at any other museum. Eventually, I found my way back to the backyard of the Fuqua-Delaney residence, knowing that it was time to return to the “real.” But I paused a moment more, smelling the rich earth, hearing the crickets, soaking it all in.